|

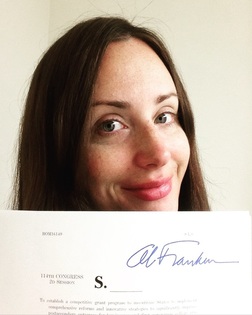

Lesson Recommendation I am always on the lookout for science lessons that incorporate art in a novel way. Recently, I found a Science Friday lesson that encourages students to create original artwork that uses the line from an actual scientific graph. My seventh graders loved this activity! Each student selected and analyzed a graph related to an environmental issue they cared about. Many chose global climate change, while others focused on overfishing, endangered animals, deforestation, and others. Students were challenged to reflect on the causes or implications of their issue and to illustrate them in their artwork. To accompany their illustrated graphs, each student wrote an Artist Statement describing the significance of the original graph and why they made their artistic choices. They also included a link and citation of the original graph. The lesson, written by educator collaborator Ryan Becker, is available on Science Friday's website. Below are some great examples of student work. Can you spot the line graphs? Student Work  A gallery of some beautiful illustrated graphs created by my seventh graders. A gallery of some beautiful illustrated graphs created by my seventh graders. This year, I left my middle school science classroom for an even more challenging and rewarding workplace— the United States Congress. Though I had to take a break from blogging while in my post, I am now able to share some reflections on my fellowship experience. So, why did move from Hawai'i to Washington, D.C. for the year? And what exactly did I get to do ? It all began when I was one of 11 STEM educators honored with an Albert Einstein Distinguished Educator Fellowship by the Department of Energy. I was then selected for a Congressional placement and, after an interview process, was matched with the Office of Senator Al Franken (D-MN). As a comedian, writer, and politician, Al Franken has been a longtime hero of mine. It was incredible to work directly with Senator Franken to help improve the quality of education for students in Minnesota and across the nation.

And when it came time for Senator Franken to deliver remarks on the Every Student Succeeds Act, he arranged for me to get floor privileges so I could join him on the Senate floor. At various times before and after the bill’s passage, I led efforts to track Senator Franken’s provisions, including analyzing bill language and funding. After the passage of ESSA, I was engaged in its implementation—staffing the Senator at hearings, synthesizing Department of Education guidance into memos, and meeting with various education stakeholder groups and the new Secretary of Education himself. While I was happy to lend my expertise on K-12 issues, I also appreciated the opportunity to expand my knowledge about higher education issues. I became more expert on Federal Perkins Loans and the Federal Pell grants very quickly, in response to Congressional action. This year, I was charged with helping to re-introduce three of Senator Franken’s college affordability bills. Two of the bills are smaller in scope: Understanding the True Cost of College Act, which would mandate that colleges use a standardized financial aid award letter and the Net Price Calculator Improvement Act, which would make Net Price Calculators (digital tools for calculating the “net price” of a particular college for individual students) more user-friendly and accessible on colleges’ websites. Another bill, the College Access Act, which was substantially rewritten, was a broad bill aimed at lowering tuition for students by incentivizing states to invest more in their public colleges. As an Einstein Fellow, I attended monthly professional development events that took advantage of unique DC resources such as meetings with the White House Office of Science & Technology Policy and a behind-the-scenes tour of the Library of Congress. As part of my fellowship, I also received funding for attending professional travel, and I chose to attend SXSWedu in Austin, the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) national conference in Nashville, the American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) annual conference in New Orleans and a Google Apps for Education training in Boston. I appreciated the freedom to direct my own learning and be provided with so many amazing opportunities.

The Albert Einstein Distinguished Educator Fellowship Program gives expert practitioners a voice in national education policy, and I am now a very proud alumna. As a Congressional Fellow, I was afforded the opportunity to immerse myself in the life of a Hill staffer and make contributions to national K-12 and postsecondary education. My accomplished cohort of Fellows enriched my experience, and I want to acknowledge how much I learned from each of them. I am grateful for my family and friends for supporting me through this fellowship year. Most of all, I want to express appreciation for Senator Franken, his legislative team, and all his staff. I had an unforgettable year in Washington, DC, but I am excited to resume my teaching practice and get back into the classroom!

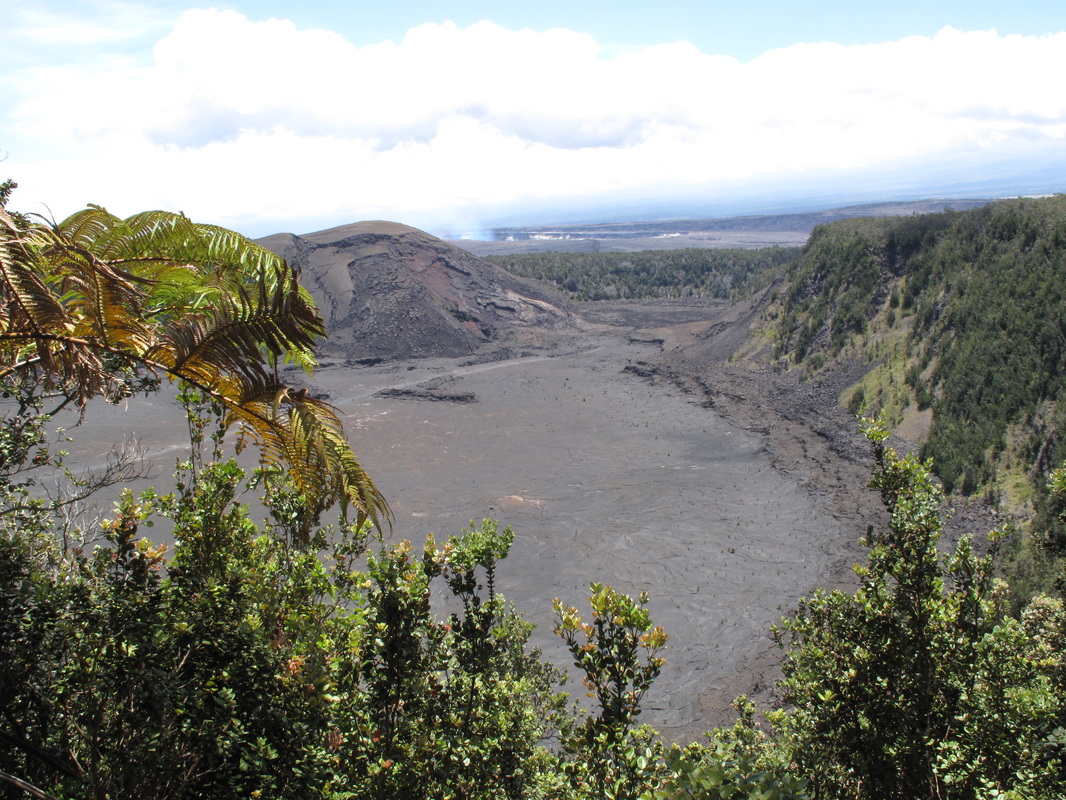

Blog Post Archive My blog posts from NOAA's Teacher at Sea website are linked below. Each blog entry is filled with engaging photographs to help tell the story. Please read about my adventures at sea! Teacher (soon to be) At Sea In this introductory blog post, I describe the Teacher at Sea program and introduce my particular cruise, a walleye pollock acoustic-trawl survey in the Gulf of Alaska. Welcome Aboard the Oscar Dyson My first post after boarding the ship in Kodiak, Alaska. Read about our scientific mission, enjoy my interview with Lab Lead Emily Collins, and take a peek inside my stateroom. Gone Fishin' Find out how scientists use acoustic data to study walleye pollock fish populations, read my interview with Survey Technician Allen Smith, and take a look inside the ship's galley. Nets and the Wet Lab Learn all about the different trawl nets employed in our survey and tour our ship's wet lab. Also, check out the gear we wear and read an interview with Lead Fisherman Kirk Perry. Sorting the Catch Read abut some of the fisheries data we collect in the wet lab, enjoy my interview with Chief Scientist Darin Jones, and check out our ship's lounge. Icthysticks and Otoliths Check out some of the novel technology we use in the wet lab, learn how fish ear bones can provide important data, and meet IT Specialist Rick Towler. Lights, Camera, Ocean! In this post, I describe how we are exploring the seafloor and its creatures with an underwater camera. Also, enjoy an interview with Ensign Benjamin Kaiser. Back in Kodiak Final thoughts on my voyage as Teacher at Sea aboard the Oscar Dyson with scientists from the Alaska Fisheries Science Center's Midwater Assessment & Conservation Engineering (MACE). Star of the Sea Bio Blitz-ers: Ready for Adventure Earlier this year, I had selected 20 seventh and eighth grade students to attend the 2015 Bio Blitz at Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park May 14th-16th and spend two nights at the park's Kilauea Military Camp. As I planned our field trip, I kept getting asked by just about everyone: What is the Bio Blitz? Well, if you break it down, bio means life and blitz implies it happens fast. Now that we have returned from our Bio Blitz adventure, I realize this name is most appropriate; we were indeed immersed in a fascinating array of life forms and our trip went by incredibly fast. So, officially, the Bio-Blitz is a 24-hour citizen science event, co-sponsored by the National Park Service and National Geographic, where teams of scientists, students, teachers, rangers, and community members collaborate to conduct a biological survey of a national park. That is, everyone works hard to find and identify as many of the animals, plants, fungi, and other organisms as possible. During the Bio Blitz, species unknown to the park are often discovered. This year's Bio Blitz, held at Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park, is the ninth of a series of ten annual Bio Blitzes that lead up to the National Park Service's 100th anniversary next year. As we gathered in the Honolulu airport Thursday morning, there was no doubt the Star of the Sea Bio Blitz-ers we were ready for adventure! Exploring the Lavascape Our mission for the Bio Blitz was a biological inventory, but as soon as we entered the Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park, we could not ignore the amazing geology. Located on the youngest of the Hawaiian islands, Big Island, the park is named for its active volcanoes. Right away, you are aware of the primal forces of volcanism that can devastate lush rainforest with lava flows; this natural catastrophe, however, is followed by new life. A dynamic cycle of destruction and renewal is evident here. As we drove down the park's Chain of Craters Road, excitement was building and students were stoked to get out and explore the lavascape.

Honoring a Sacred Place One of the objectives for the Bio Blitz was to develop a sense of place and appreciation for biodiversity through field study in the local environment. Fortunately, the organizers of this year's Bio Blitz recognized the intimate connection between native Hawaiians and the natural world and made efforts to integrate indigenous knowledge and cultural protocol. In fact, the Bio Blitz alakai'i (cultural practitioners) led the students in komo (entrance) and mahalo (gratitude) 'oli (chants) to begin and end each student inventory. Click here for a copy of both chants in Hawaiian (with English translation). To help our Star of the Sea group prepare for visiting the sacred places of Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park, I had invited local kumu Toni Bissen, executive director of the Pūʻā Foundation, to provide students with relevant cultural knowledge. Through interactive lessons during an all-day retreat, we investigated the land divisions, ahupua'a, on Big Island, as compared to O'ahu. Kumu Bissen also helped us practice our 'oli and plan our ho'okupu (gift) to Pele. Another fantastic resource has been Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park Cultural Anthropologist Keola Awong. She shares her perspective on Bio Blitz in an interview with National Geographic: "Traditional Knowledge Helps Us Understand Nature in Every Sense." The komo 'oli, composed by Kepā Maly and performed by Keola Awong:

Look out invasive ginger, here we come! Himalayan ginger was brought to Hawai'i as an ornamental plant due to its beautiful and fragrant flowers. In fact, it is also called kāhili ginger for the flowers resemblance to a kāhili , a feather staff Hawaiians displayed in the presence of royalty. Unfortunately, this ginger has escaped local gardens and become one of the most invasive plants in Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park, growing rapidly and completely replacing the native rainforest understory. Due to its propensity to choke out native Hawaiian plants, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature includes Himalayan ginger on the "100 of the World's Worst Invasive Alien Species" list. So, before our Bio Blitz experience officially began, I decided we were going to spend a few hours serving the park by removing this invasive ginger. Volunteers Paul and Jane Field provided our Star of the Sea crew all the knowledge and tools needed for the task. After donning gloves, students grabbed their loppers (cutting tools) and got to work. Students slashed their way through a large marked area, cutting huge gingers to about knee-high and stacking the lopped stems in clear areas. The Fields will return to the area later and apply a low-concentration herbicide to the exposed stems, which will kill the gingers and not affect the native plants.

Students Bio-Blitz the Rainforest! On Friday morning, the official Bio Blitz Student Inventories began. These inventories, held simultaneously at five different rainforest sites in the park, were conducted by over 800 students from many different Big Island schools. Star of the Sea School, however, was the only participating school from another island. Students engaged in three different rotations: plants, birds, and arthropods. During each rotation, students learned about how scientists identify and classify members of those groups. Students used the iNaturalist app on their mobile devices to photograph, identify, and map species they found, adding the observations to the official Bio Blitz inventory.

At the plant rotation, students were most impressed to see the hapu'u, giant tree ferns endemic to Hawai'i. The fern's massive fiddleheads were covered with a silky fluff called pulu that protects the young fronds; native Hawaiians used pulu as an absorbent dressing for wounds. The students learned about how scientists set up transects and quadrats to measure plant diversity of an area. In the arthropod rotation, students got to find and classify tiny insects such as mites, crickets, and beetles. A large white 'beating sheet' was placed beneath a tree branch, and when the branch was beaten with a stick, arthropods fell out onto the sheet. To get tiny insects into smaller vials, students used a collection tool called an aspirator. Though you provide the suction on an attached tube to move the insect, a screen prevents you from sucking it into your mouth!

Don't Worry, Be Happy (Face Spiders!)

Our helpful Bio Blitz liaison, park volunteer Arthur Wierzchos, instructed us how to look for the rare spiders by carefully peering under the leaves of Kolea and Kawa'u trees. Arthur assured me that the spiders were in this area of rainforest, but he stressed that they can be quite hard to find. Within our first 30 minutes, Arthur spotted a female spider with eggs and we all got to see it! In the few hours, we found four more adult spiders, including three females and one male. Melia and Kayla found one female guarding about fifty baby spiders! The Bio Cube: Not So Square One of the student groups had the opportunity to participate in a Bio Cube project with acclaimed naturalist photographer David Liittschwager, who often works with National Geographic and Smithsonian. Our aim was to set up David's green metal frame, one cubic foot in area, in a diverse habitat and carefully identify and document all the life within it. It's a Bio Blitz on a small scale. In Smithsonian Magazine's The Insane Amount of Biodiversity in One Cubic Foot, David describes his One Cubic Foot book and mission. He makes a case for why these small spots, and small creatures, matter. While in the field with students, David took the time to give students technical tips on how to best photograph the plants and animals. We had a lot of fun scoping out a spot to put the Bio Cube, and we finally placed it in a gully dripping with mosses, liverworts, ferns, and other plants.

There's Fungus Among-us Another student group started their afternoon by hiking the Kilauea Ike trail through lush rainforest all the way down to the solidified but still-steaming crater floor. Students followed the lightly etched trail across the lava field and saw steam vents, cinder cones, and spatter cones. Hard to believe that this field formed in 1959, when Kilauea Ike's Pu‘u Pua‘i cinder cone erupted and sent lava fountains almost 2,000 feet in the air! Students were stoked to explore this volcanic landscape together.

All specimens that were collected will be accessioned in the University of Hawaii's Rock herbarium; if fungi cannot be identified using macroscopic or microscopic features, then DNA sequencing will be utilized to help with the identification. Some of the inventory's samples have been found in the park before, while others are likely new records. Way to go, fungus finders!

Celebrating Biodiversity & Hawaiian Culture! As a way to further marry science and culture, the park hosted the Volcanoes Biodiversity and Cultural Festival during the Bio Blitz. The festival featured a variety of exhibits, demonstrations, and hula and musical performances. Before we departed from the park on Saturday, students were excited to spent some time at the festival's many educational booths and try their hands at some traditional Hawaiian crafts. As we set out on this sunny day, the wide, shield-shaped dome of the park's other active volcano, Mauna Loa, was visible. In fact, Mauna Loa is the world's largest active volcano, with an elevation of 13,680 feet and encompassing 10,000 cubic miles. On our walk, we also saw some more of the park's unique features.

The Bio Blitz was a huge success and at the Closing Ceremonies we learned that over 1500 observations were uploaded into iNaturalist. And over 400 different species were formally identified by scientists, students, and community members in 24 hours! Read more about the official inventory results here. It was also announced that the 2016 Bio Blitz will be held in Washington. DC, with associated events held in national parks nationwide.

I would like to extend a big MAHALO to...

In closing, the mahalo 'oli, composed by Kepā Maly and performed by Keola Awong:

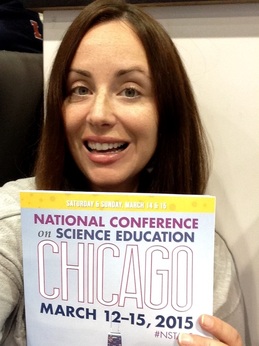

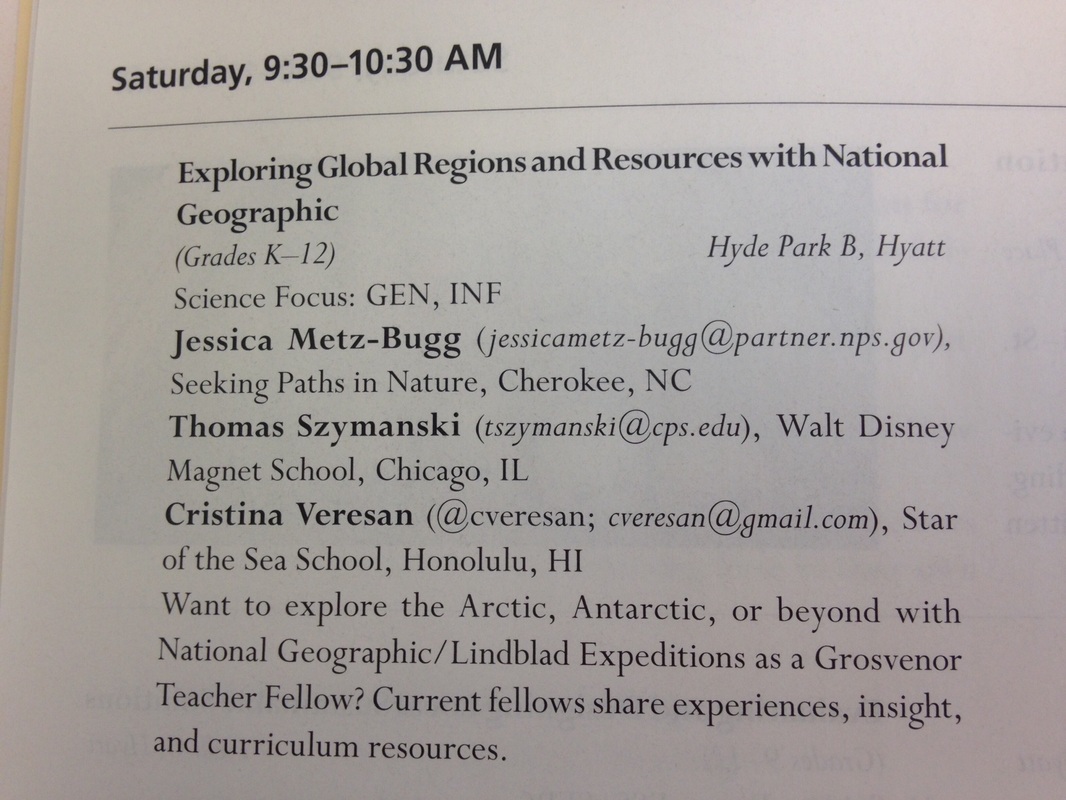

The (Cold and) Windy City Chicago's famous football team, the Bears, was not named for the polar variety, but I came to this city to share about my Arctic expedition— a story of polar bears and sea ice! I was selected to deliver a workshop at the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) conference along with two other Grosvenor Teacher Fellows, Mrs. Bugg from North Carolina and Mr. Szymanski from right here in Chicago. We wanted to let teachers know about this amazing National Geographic/Lindblad Expeditions fellowship that brings teachers on voyages of discovery all over the world.

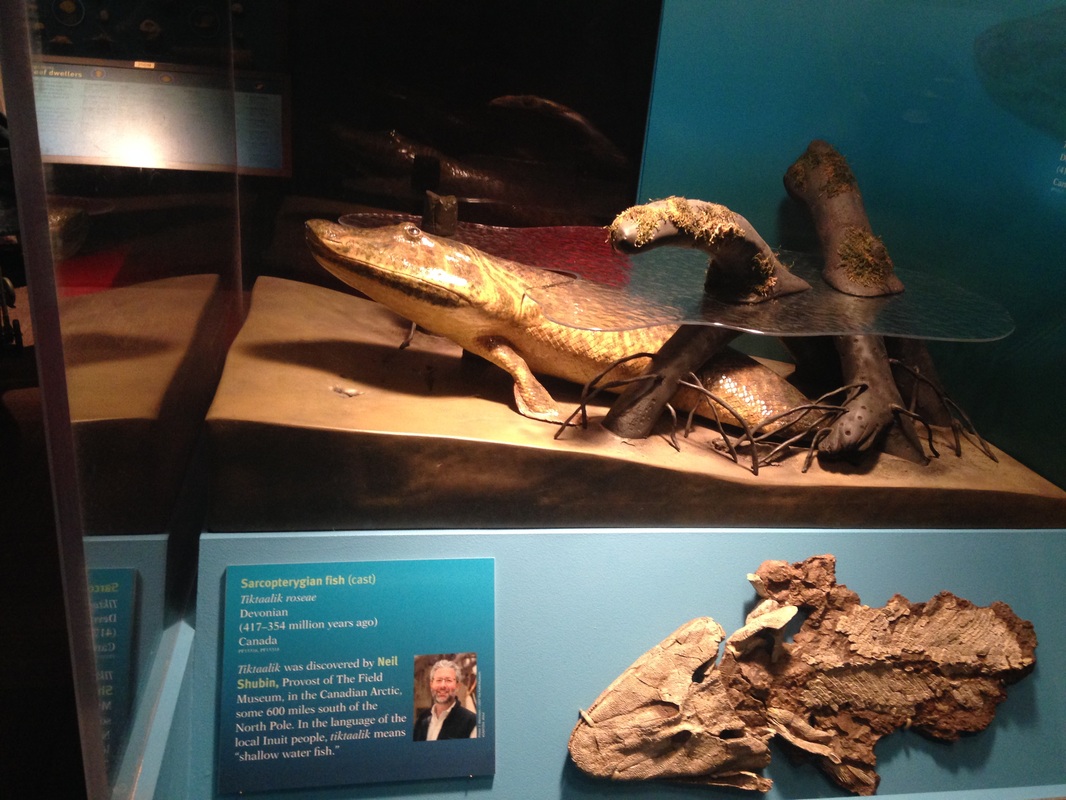

In Dr. Shubin's talk, and Your Inner Fish, he also tells the story of his research team's 2004 discovery in the Canadian Arctic of Tiktaalik roseae, a 375 million year old fossil fish that has both fish and amphibian traits. Thus, Tiktaalik is an important transitional fossil between fish and tetrapods (creatures walking on land). In delivering his address, Dr. Shubin emphasized that science is a collaborative endeavor; that is, scientists work together to conduct investigations and solve problems. Though now based at the University of Chicago, Dr. Shubin had also served as Provost of Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History. I planned to visit this museum before I left Chicago.

Our Presentation This morning, about 30 teachers attended our session, and they were a very enthusiastic audience! Our talk was entitled "Exploring Global Regions and Resources with National Geographic." Mrs. Bugg, Mr. Szymanski, and I had all taken different voyages aboard the National Geographic Explorer through our fellowship: Mrs. Bugg journeyed through the Canadian Maritimes, Mr. Syzmanski got to explore Antarctica, and I, of course, was cruising through Arctic Svalbard. Our talk introduced the Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship and described our particular voyages using expedition photos. We emphasized the importance of imparting geo-literacy to students; that is, an awareness of global interactions, interconnections, and implications. So, we tried to describe how our adventures enriched our own geo-literacy of the regions we explored and how it impacted our teaching. Expeditionary learning can be incredibly powerful!

Soon I would be actually traveling back to Hawai'i. I have learned a lot, but I am anxious to get back home to the warm weather and my wonderful Star of the Sea 'ohana. Aloha Chicago!

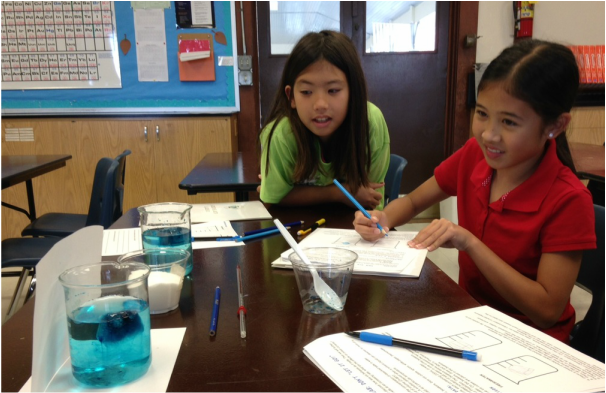

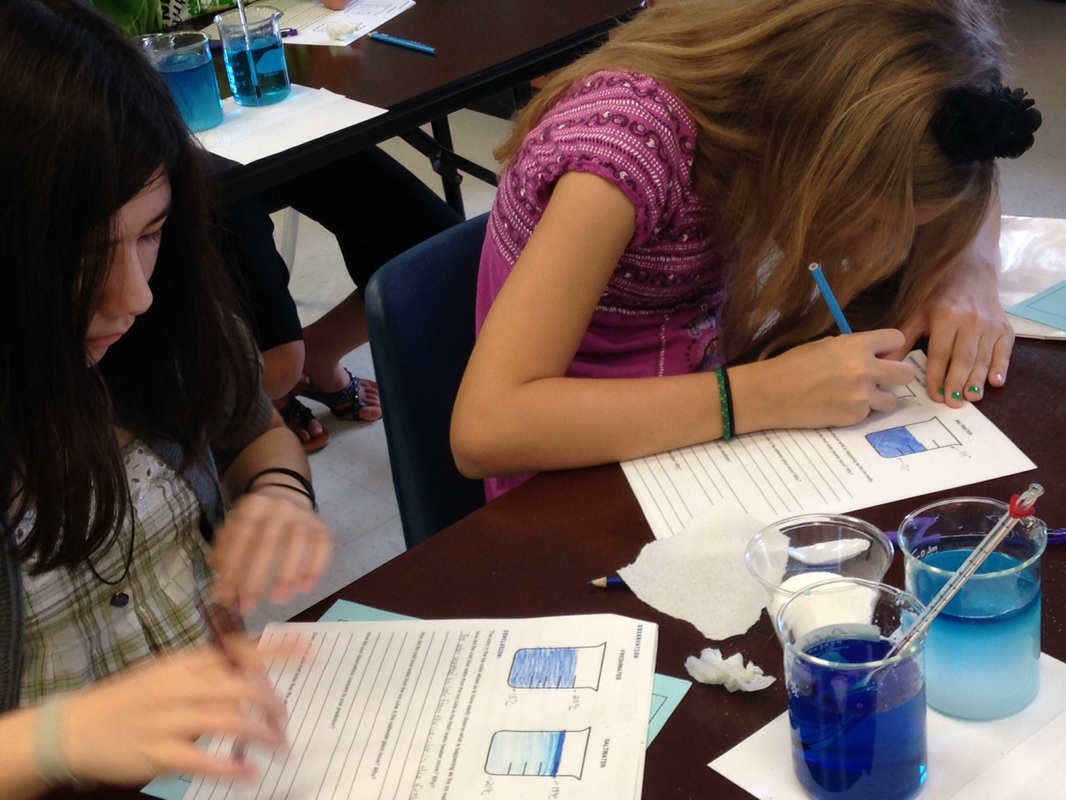

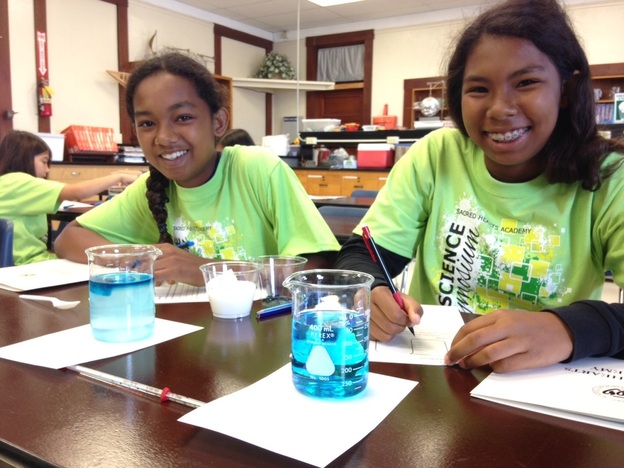

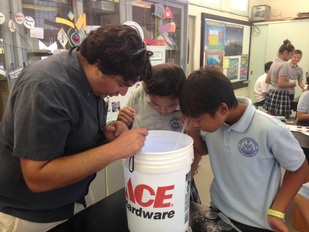

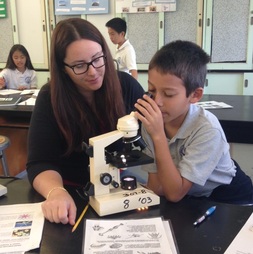

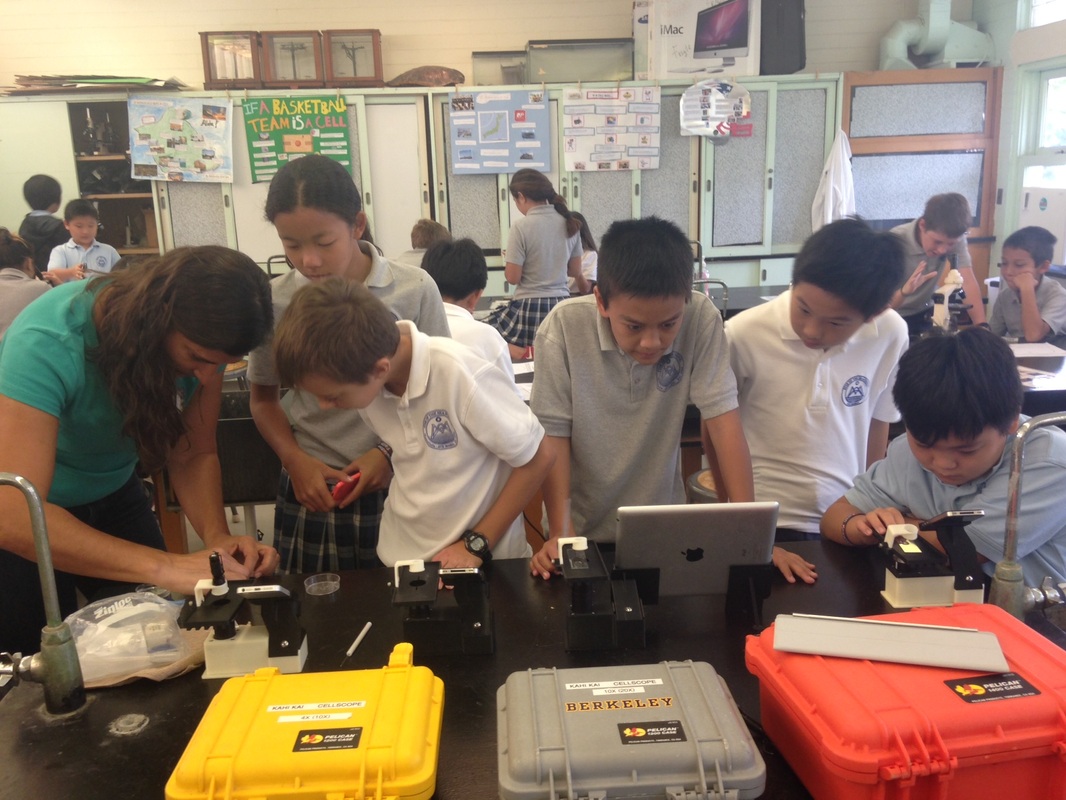

Encouraging all STEM Learners Early this fall, I was contacted by one of the organizers of the Science Symposium for Girls here in Honolulu. She had seen me on the local news talking about my Arctic expedition as a Grosvenor Teacher Fellow, and she asked if I would be willing to present about the Arctic at this year's symposium. I could not pass up the opportunity to work with 5th-8th grade girls from island schools in the 2015 Science Symposium for Girls. The symposium, now in its 21st year, is presented by Sacred Hearts Academy in partnership with Bank of Hawaii Foundation. Females are often discouraged from STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) subjects in school and are still underrepresented in potentially lucrative STEM careers. But why? While inherent gender differences have been ruled out by science, multiple environmental and social barriers influence the complex issue of female participation and achievement in STEM subjects. According to current research, these factors include persistent gender-bias about traditional male and female fields, a fixed mindset rather than a growth mindset for intelligence, lack of spatial skills training for girls, and a lack of confidence and feeling of isolation for girls in STEM subjects. My Symposium Workshop I believe events like the symposium can not only boost girls' confidence in STEM but also help them develop relevant skills. Moreover, girls interested in STEM gain a sense of community through collaborative work. If we are going to increase our nation’s STEM participation and achievement, we need to support all learners! Therefore, I was honored to be invited to participate in today's symposium. As a featured presenter, I delivered a workshop to two different groups of 20 girls. For my workshops, I decided to focus on sharing about my Arctic expedition with a Prezi for the first half of the session and use to second half for an ice inquiry investigation. First, I introduced how I was able to travel to the Arctic through a teacher fellowship through National Geographic and Lindblad Expeditions. Next, I defined the Arctic region and pointed out some facts about Svalbard, the land of the Ice Bears. I shared the Arctic scenery and wildlife through my expedition photos. In my talk, I told the story of how the polar bear depends on sea ice for survival. These top predators rely on the sea ice in order to hunt seals. However, I explained to the girls that like the polar bear, our planet also depends on sea ice. One reason we need sea ice is critical habitat for Arctic wildlife, from crustaceans to seabirds to walrus to the iconic polar bear. Also, our ice-covered polar regions reflect much of the incoming solar radiation, regulating global climate. In addition, sea ice plays an important role in the ocean conveyor belt, the global transport of seawater. Next came the hands-on part of the session! The ice inquiry allowed the girls to practice making predictions and then collecting data while investigating if an ice cube (dyed with blue food coloring so water is easier to observe) melts faster in fresh or salt water. We then discussed how temperature and salinity each affect density and related the concepts to the ocean conveyor belt. The girls in each session asked a lot of thoughtful questions about the Arctic and were really engaged in the lab portion as well. It was an awesome day of learning!

Mahalo to Mr. Raphael and Miss Anuschka for helping us see the "invisible" world of plankton!

Our Outdoor Classroom Today, middle school students once again enjoyed a day in the best kind of classroom: nature! We spent the day at Sandy Beach Park in Hawai'i Kai, where students investigated the impacts of climate change in our local environment. This field study was the makai (coastal) component of our From Mauka to Makai: Understanding Climate Change Impacts in the Ahupua’a program, a partnership with the Hawai'i Nature Center. Today's outdoor science learning included a lesson on marine debris and an opportunity to help clean up the beach. Students also explored the tide pools, assessing environmental conditions and biodiversity. I think everyone's favorite part was searching for creatures in the intertidal zone. Marine Debris and Garbology

Human debris, or garbage, from both land and sea collects in the ocean and ends up on our beaches. Unfortunately, about 90% of marine debris is plastic, which is not biodegradable. This plastic trash, ranging from micro to massive, has far reaching impacts and is very dangerous for birds, turtles, and marine mammals. We can all make a difference by using less and properly disposing or recycling unwanted items. Another great way to help out is by participating in local beach clean-ups. On our island, almost every weekend there is a beach clean-up where you can volunteer with your family. Tide Pool Study When I was a little girl on the New Hampshire coast, my favorite activity was to explore the tide pools, scrambling along the rocky intertidal zone from pool to pool. I would lift up big piles of seaweed and scan for scurrying crabs and clinging sea stars. I would wade in the deeper pools. And I would always remember what my father taught me: you can pick up a rock to look underneath but always put it back just as it was— something makes a home there. Tide pool exploration was an important training ground for a curiosity about the natural world and a career in science education. Thus, it is always a pleasure to share this particular outdoor classroom with students. In October's mauka study, we talked about how conditions in the uplands affect the marine environment below. From the mountains to the sea, our watershed is interconnected and interdependent. Pollution and sediment are often carried by streams and channels to the estuaries and eventually the ocean. The estuary, where the fresh and salt water meet, is a critical nursery, as well as important habitat for organisms like the Hawaiian 'o'opu whose life cycle includes both stream and ocean environments. Here at Sandy Beach Park, students conducted a field study similar to that of the stream study, this time in coastal tide pools. Students made predictions and then assessed tide pools in different intertidal zones: upper, middle, and lower. In each of the tide pools studied, student measured and recorded pH, dissolved oxygen, temperature, and other environmental data. Students also searched for creatures in the tide pools to quantify the biodiversity.

The more time we spend in nature, the more we appreciate its beauty, resources, and diverse array of living things. We have to make our home while allowing other creatures to keep their homes. If we come to love nature, we will fight to protect it. So get out there and explore your world!

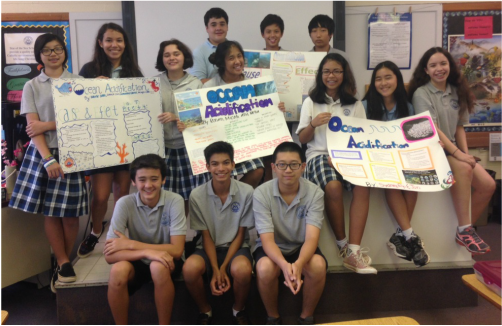

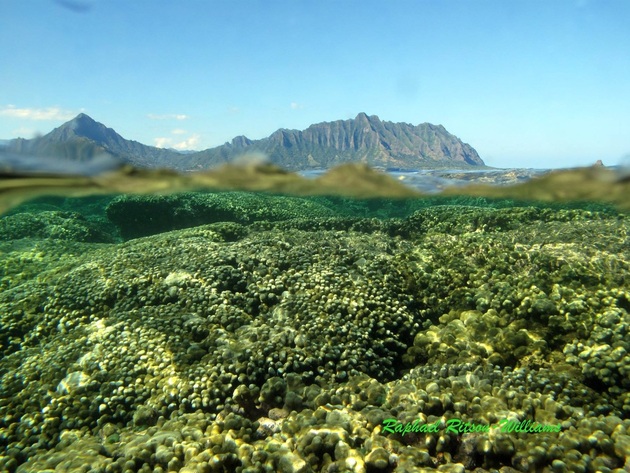

Ocean Chemistry By now, we are familiar with the concept of global climate change due to humans burning excessive amounts of fossil fuels that release carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. However, not all carbon dioxide ends up in our atmosphere. Approximately 1/3 of that carbon dioxide ends up getting absorbed by the ocean, where it is causing ocean acidification. This issue, which you may not have heard much about, is a serious threat to shell-forming plankton, corals and other organisms. So, how are the oceans becoming more acidic? What are the potential effects of ocean acidification? 8th graders students have been investigating these questions during an applied chemistry unit.

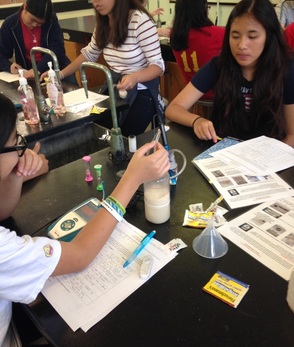

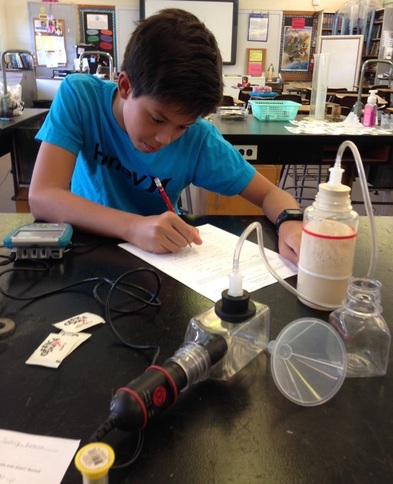

Modeling Ocean Acidification So students could explore ocean acidification first hand, I borrowed a kit from the University of Hawaii's Center for Microbial Oceanography: Research and Education (C-MORE). The kit had all the materials for an experiment that simulated ocean acidification using active yeast to generate carbon dioxide. Students used Lab Quest handheld computers with probes to measure the carbon dioxide generated by the yeast and the effect of this carbon dioxide on the pH of water. Yeast, a living fungus that respires, was placed in a bottle with sugar and water to activate it. The carbon dioxide gas released by the yeast respiration was directed through rubber tubing to two different places: a chamber of air, where carbon dioxide was measured by a special probe and a bottle of water, where the pH was measured by another probe. In the investigation, students observed the carbon dioxide levels dramatically rise as the pH slowly lowered. When they graphed and analyzed their data, students discovered for themselves the relationship between carbon dioxide and pH. Protect Our Coral Reefs

In addition to our hands-on labs, students have also been analyzing atmospheric and ocean data sets that indicate a rise in carbon dioxide that contributes to global warming and ocean acidification. Moreover, we have discussed the real-world impacts of these issues. One of the most devastating predicted consequences of ocean acidification is the degradation of reef-building corals. Here in Hawai'i, we rely on healthy coral reefs for the diverse array of life they support, as well as their recreational uses, fishing resources, and shoreline protection. Let's work together to combat ocean acidification, another disastrous consequence of climate change. How will YOU make a difference? Energy in Hawai'i In our studies relating to climate change, my students have been researching Hawai'i's energy production and consumption. We are very fortunate to have multiple renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, biomass, hydroelectric, and geothermal, but renewables only account for about 8% of our total energy consumption. Over 85% of our energy comes from domestic and international petroleum imports. That's right, most of our electricity comes from the burning of oil. One energy source that really interests my students is solar energy. Despite the intensity and duration of our sunlight here in the tropics, students were surprised to learn that less than 2% of our energy consumption comes from solar energy. Yet progress toward a more energy-independent Hawai'i is being made, and solar energy is increasingly popular. In fact, right now, photovoltaic panels are being installed on the roofs of our school that will convert solar energy into electricity to power Star of the Sea. Engineering Solar Ovens But how about harnessing solar energy to cook food? Solar ovens, also called solar cookers, convert sunlight into heat energy, which gets trapped in the oven and raises its temperature. My students were challenged to design and build a solar oven that would maximize solar heat gain and retain the heat for cooking. To construct their ovens, the students used common household materials, including many reused and recycled items such as chip bags, newspaper, and shoe boxes. Solar ovens should be covered with reflective material, such as aluminum foil, in order to catch as much sunlight as possible. Used chip bags, cleaned and turned inside out work well for this purpose. There needs to be a window-like opening on the top of the oven covered with clear plastic. Most students left the flap when they cut the opening which was then engineered so the angle could be adjusted. Sunlight, both direct and reflected, enters the oven through this clear opening and gets trapped. Crumpled newspaper is a good insulator to line the inside of the box. Black construction paper works well as a cooking surface on the bottom of the box because it absorbs a lot of heat. If you've ever worn a black shirt on a hot day, you understand this concept! Our Solar-Oven Cook-Off!

|

AuthorThis blog contains occasional dispatches from my science classroom and professional learning experiences. Thank you for reading! Archives

December 2021

|

|

Cristina Veresan

Science Educator |

Proudly powered by Weebly

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed