Grosvenor Teacher Fellow AlumnaTo my delight, I was offered a chance to join a National Geographic-Lindblad Expeditions Galápagos expedition as a Grosvenor Teacher Fellow Alumna. It was a tremendous professional honor and a unique opportunity to explore a place that has long fascinated me. On expedition, I gained firsthand knowledge of Galápagos wildlife, geology, and natural history as I followed in the footsteps of Charles Darwin. Now that I have returned from my voyage of discovery, I am just beginning to process all that I have learned. The Galápagos archipelago is a province of Ecuador and straddles the Equator in the eastern Pacific approximately 600 miles from the mainland. It's comprised of 13 large islands and over 40 small islands, islets and rocks. The total land area of the Galápagos islands, just over 3,000 square miles, is about half the size of Hawaii. In 1959, the Ecuadorian Government declared all uninhabited areas of the Galápagos Islands a National Park (a total of 96% of the total area). Since the 1960's the Galápagos National Park Service has managed the park with help from the Charles Darwin Foundation for the Galápagos Islands, a private non-profit scientific and conservation organization. The region's unique cultural and natural treasures made Galápagos the world’s first UNESCO World Heritage Site. What a place to explore! So, on Thanksgiving, I flew out of San Francisco on a seven hour red-eye flight to Panama City, Panama where I was thrilled to find a Dunkin' Donuts to buy a coffee. After a brief layover, I flew to Guayaquil, Ecuador to spend the night at a hotel. The next morning it was time to fly to San Cristobal Island. There, we had to clear additional customs and familiarize ourselves with Galápagos National Park rules. It was finally time to check out the port and board the National Geographic Endeavor II. Lindblad Expeditions has over 50 years experience in Galápagos: read about the ship here; and get more information about travel with Lindblad in the region here. Day 1: San Cristobal and Boarding the ShipGetting to know my fellow travelers, the naturalists, and the photo instructors was so much fun. Also, I was not the only Grosvenor Teacher Fellow Alumni on expedition. I had a fabulous partner in Kelly Meade from Long Beach, California. At David Starr Jordan High School, Kelly teaches Medical Chemistry and Epidemiology & Public Health. We bonded right away, and I was so stoked to share a cabin, and this adventure, together. I am also grateful because Kelly was able to document the experience with some sophisticated cameras, whereas I was just using an iPhone (on land) and an old GoPro (underwater). Check out Kelly's amazing photos and insights on her blog here. Though the National Geographic photographers, and most guests, had impressive camera equipment, one of the Galápagos National Park rules relating to photography is that you are not allowed to use a flash (on land or underwater). About 30,000 people live in the Galápagos. Only four of the large islands (Santa Cruz, Isabela, Floreana and San Cristobal) are inhabited. This city, Puerto Baquerizo Moreno, here on San Cristobal Island, is the capital of the Ecuadorian province of Galápagos. The island residents primarily make a living from tourism, fishing and farming. Day 2: Gardner Bay & Punta Suarez, EspanolaWe had Gardner Bay all to ourselves this morning. I quickly found out that the Galápagos National Park strictly regulates this and other sites by rotating groups through on a schedule, so we never saw another tour group at our landings or snorkel spots. You do, however, have to be in a group with a certified park guide/naturalist all times and you must stay on established trails. This particular beach is known for dazzling white sand! The sand is a result of millions of years accumulation of the organic waste of fish, breakdown of corals, and deposition of calcium carbonate; after many years of erosion, the sand develops a very fine texture. The beach is also known for its charismatic Galápagos sea lions. This endemic species of sea lion, found throughout the islands, is a separate species than its California sea lion relatives. When we got to port in San Cristobal one of the first creatures I saw were the endemic Sally Lightfoot crabs (Grapsus grapsus) scrambling on the rocks below the dock. In fact, they can be seen feeding in large groups on most beaches and in shallow water on all the islands. Here, at Gardner Bay, I finally got close to these colorful crabs! These scavengers provide ecosystem services like cleaning organic debris and eating ticks off marine iguanas. In the afternoon, we took a long hike around Punta Suarez, and were treated to some spectacular scenery and wildlife. Though the Galápagos has relatively low biodiversity, it has high rates of endemism—organisms separated from their main population and adapted to their environment, eventually changing to become a new species. There are as many as 26 endemic species among the islands including Darwin’s finches, Galápagos giant tortoises, marine iguanas, and Galápagos penguins. This is the only place on earth you can see these animals in their natural habitat. And because Galápagos animals have no instinctual fear towards humans, you closely encounter wildlife. Galápagos National Park rules require visitors stay 6 feet (2 meters) minimum distance from wildlife, and it is unbelievable to be so close to these rare and wild creatures. I think of all the famed Galápagos wildlife, I was most excited about seeing the endemic marine iguanas. The world’s only swimming lizards, these iguanas were the inspiration for Godzilla’s visage. They forage algae underwater, so they ingest large amounts of seawater. I learned two things about this: they loudly “sneeze” out the excess salt without losing water due to special glands; and they usually do it right after I stop videoing them. A large population of waved albatrosses breed and nest here on this island. The waved albatross is the largest bird in Galápagos with a wingspan of over six feet, and they are phenomenal gliders that spend most of their lives offshore. We were lucky to see pairs courtship dancing, which included bill circling, bill clacking, and head nodding. Waved albatross couples mate for life and each breeding season the female lays a single egg on bare ground which the couple take turns to incubate for up to two months until it hatches. Day 3: FloreanaWith three snorkels, most of today was spent underwater, but I did have the opportunity to go for a morning photography walk on Floreana island. Although the Galápagos Islands were visited by pirates, buccaneers and whalers from the late 1500s through the early 1800s, they remained unclaimed until 1832 when Ecuador officially took possession of the islands. In 1832 people first began to colonize Floreana Island, which eventually turned into a penal settlement. Repeated colonization attempts by penal colonies and settlers, largely unsuccessful, occurred for another century. We hiked inland to a brackish lagoon to see a flock of American flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber). Dozens of flamingoes were foraging for food in the mud. Their lovely pink coloration is determined by the amount of carotenoid pigment that they ingest in their food sources (algae, crustaceans and tiny plant material); the more carotenoid pigment a flamingo consumes, the more intense their pink color. I was so excited because I saw my first blue-footed boobies! Their odd name comes from the Spanish '‘bobo’, meaning foolish/clown, on account of their clumsy movement on land. Their most distinctive characteristic is obviously their large blue feet, which play an important role in courtship. Females are thought to select males with brighter feet, as they are an indicator of his fitness and the quality of his genetic material. Thus, males make quite a performance of showing off their feet! Galápagos National Park rules prohibit collecting anything, but it was still fun to go beach combing and find shells, sea turtle bones, and various sea urchin tests. Day 4: Puerto Ayora/Darwin Research Center/Highlands, Santa CruzToday we were off the ship the entire day on the island of Santa Cruz. We were shuttled by Zodiac to the bustling port city of Puerto Ayora. Over half of all “Galapagueños” live in this city, and it's the center of tourism and conservation. Puerto Ayora has the best developed infrastructure in the archipelago. The small downtown area has some hotels, restaurants, tour companies, convenience stores and gift shops. The main street, Avenida Charles Darwin, runs between the main dock and the Charles Darwin Research Station. Along this avenue, I was absolutely captivated by an outdoor fish market. Men cleaned the day's catch as frigate birds swooped in and pelicans and sea lions circled their feet. Locals came up to make purchases while tourists and policemen watched the scene. My pictures of the fish stall in Puerto Ayora, Galápagos illustrate connections between the human and natural world that I try to address in my science courses. To engage student curiosity, I’m going to use it as the focus of a See-Think-Wonder exercise in class. Educator-Explorer friends, consider using this powerful thinking routine with some rich images from your own travels.  We toured the Charles Darwin Research Station and Museum. I had been really looking forward to this, as the foundation's Executive Director Dr. Arturo Izurieta Valery has been a featured guest speaker onboard the ship and he and his wife were frequently on excursions with me. The mission of the Charles Darwin Foundation is "to provide knowledge and assistance through scientific research and complementary action to ensure the conservation of the environment and biodiversity in the Galapagos Archipelago." Read more about the Charles Darwin Research Station on their website. I loved seeing all the different species of tortoises in their captive breeding program. They had tortoises at all stages of life from baby to elder. I felt a bit melancholy seeing Lonesome George, though. A male Pinta Island tortoise and the last known individual of the species, George was cared for at the research station for forty years (by the same primary caretaker) until his death in 2012. After his death, Lonesome George was shipped to New York and underwent a taxidermy process by experts at the American Museum of Natural History before being returned to Ecuador. Now a preserved specimen on display, Lonesome George is still an important symbol for conservation efforts in the Galápagos islands and the world.

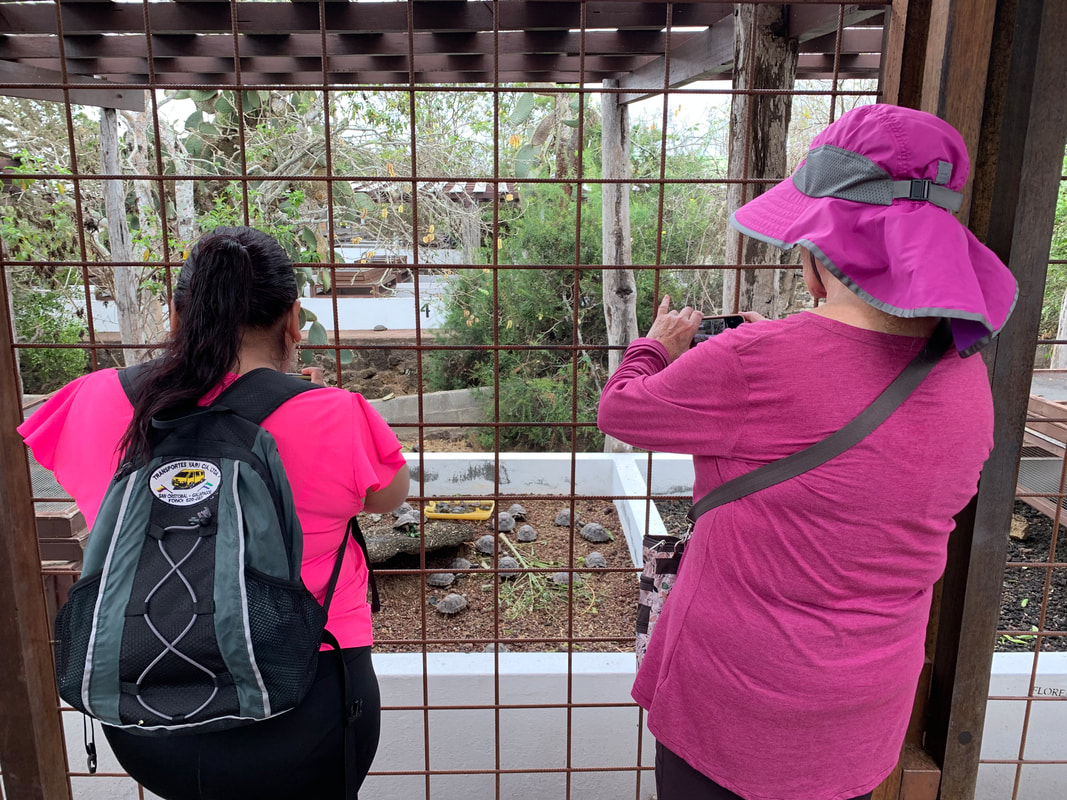

Darwin arrived in the Galápagos Islands on September 15, 1835. He spent just five weeks in the archipelago, but he later wrote that the wildlife of the Galápagos islands were central to all his scientific thinking. While in the islands, Darwin, who suffered from seasickness, spent most of his time taking notes on land features and collecting specimens of unknown species. Upon his return to England, as he reviewed his notes and specimens, he began to develop his “Theory of Natural Selection." Twenty years after he first postulated the theory, due to both desiring more data and ducking controversy, he would finally publish On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. His radical idea, the driving force behind evolution, is the central unifying theory of biology. While adventuring with the support of National Geographic Education and Lindblad Expeditions as a Grosvenor Teacher Fellow Alumna, I had a chance to learn about Lindblad’s education initiatives in Galápagos. First, that afternoon in Santa Cruz, I visited Tomás de Berlanga, a bilingual PreK-12 school that has a project-based approach to learning and a campus fully immersed in nature. I loved the playground: no foam mats or AstroTurf here. The school receives funding from Lindblad Expeditions, including support for its lending library— the first of its kind in Galapagos! I was pleased to bring a few new books I had bought at the Nueva School Book Fair as donations. Second, despite a language barrier, I got to know three teachers from Galapagos that were invited guests on the voyage. In fact, Lindblad Expeditions has sent hundreds of Ecuadorian teachers on expedition in the archipelago over the years. I am proud of this commitment to local education. We had lunch and spent the rest of the afternoon up in the lush, rainy highlands. Observing Galápagos giant tortoises (Chelonoidis nigra) in the wild is a thrill, but you have to be careful where you step! I saw the herbivores lumbering through field and forest. The “giant” tortoise title is well-deserved— they can get up to 500 pounds! They are the longest-lived of all vertebrates, living more than 100 years. Centuries of being hunted for food left populations critically endangered but the species has been protected by the Ecuadorian government since 1970 and repopulation efforts by the Charles Darwin Research Station have been very successful. Fun fact: though they are largely solitary roamers, a group of tortoises is called a creep. Love that collective noun! Day 5: Cerro Dragon, Northern Santa CruzToday, was all about trying to find the elusive Galápagos land iguanas (Conolophus subcristatus) on a long hike in the northern part of Santa Cruz island known as Cerro Dragon or "Dragon Hill." The sun was scorching and the dry landscape was covered in sparse stands of cactus and palo santo trees, the latter giving the air a slightly sweet licorice smell. Remember, Santa Cruz is the island with the largest human population in Galápagos, so unfortunately, many domestic animals have gone feral; wild goats, cats, and dogs had been decimating the iguana populations for decades. However, recent efforts of the Charles Darwin Foundation and the Galápagos Park Service to re-populate the iguanas and remove feral animals have been effective, and the iguana population has been on a steady increase. We were determined to find some of these dragons! We saw four individual Galápagos land iguanas but they were pretty far off the trail, and it was hard to get a good picture with my iPhone. Luckily, Kelly shared some of her pictures like the one below. The Galápagos land iguana is one of three species of land iguana endemic to the archipelago (one of the others being a pink Galápagos land iguana). Their skin is generally yellow with white and brown blotches. They have short heads and powerful hind legs with sharp claws. Despite the threatening appearance, they are primarily herbivores who feed on fruit and prickly pear leaves. These large reptiles have a mutualistic relationship with finches, who eat ticks from their scaly backs. Did you know Galápagos native flowers are only either white or yellow? There are few insects in the archipelago, so plants don't have to work as hard to compete for their attention. Because, you know, evolution. Day 6: BartolomeToday was all about geologic wonders and sweeping vistas while hiking on Bartolome islet. The Galápagos Islands are one of the most active oceanic volcanic regions on Earth, and I was definitely reminded of this while on the near-barren, almost Martian landscape. The islands are on the Nazca tectonic plate, above a hot spot that produces a plume of hot magma, adjacent to a mid-oceanic ridge, atop what's known as the Galápagos Spreading Center. When magma finds a weak spot in the plate above, it rushes to the surface, creating a volcano. The volcano is eventually carried away from the hot spot by plate movement and a newer volcano is created in its place. Thus, over time, the hot spot made the Galápagos archipelago. The Nazca plate is moving in a south-easterly direction, so where are the oldest island in the island chain located? Very few plan species can survive this drought-prone habitat, but there are some low-growing plants, lichens, and native cactus. I loved seeing the sooty lava flows and rust-colored "spatter cones.". The islet's golden sand here originates from the ochre-colored tuff cones that are comprised of silt loam and have a clay-like texture. On account of the strong ocean breezes here, erosion occurs daily. To help control erosion, the "trail" is a wooden boardwalk and a series of staircases (376 steps in total!) that lead to the summit of the islet. The view from the top is stunning, with a near 360-degree view of the surrounding islands and the iconic Pinnacle Rock formation. Pinnacle Rock, an old volcanic cone, was formed when magma was expelled from an underwater volcano; the sea cooled the hot lava, which then exploded, and many thin layers of basalt formed the rock. Some say Pinnacle Rock looks like a shark tooth, some say a sail. The afternoon was spent snorkeling down at the base of Pinnacle Rock, and I felt so fortunate to see some endemic Galápagos penguins (Spheniscus mendiculus) both on the shore and under the water! Sighting them is very rare. They’re the only penguin found north of the Equator and cool ocean currents allow them to live in the tropical latitudes of the archipelago. The weather here is periodically influenced by the El Niño events, which occur about every 3 to 7 years and are characterized by warm sea surface temperatures, a rise in sea level, greater wave action, and a depletion of nutrients in the water. Past El Niño events have resulted in an approx. 75% population mortality due to prey species decline and reduced breeding success. There are currently less than 1,500 individual Galápagos penguins left. Climate scientists predict that future El Niño events will become more frequent and severe due to global climate change; has the fate of this endangered species been sealed? Day 7: GenovesaToday, I went on a few different hikes in the birder's paradise known as Genovesa island. Because it is somewhat remote, many land species never made their way to this island, allowing birds to dominate. Indeed, thousands of birds nest here. As we approached the island, storm petrels, boobies, and great frigates filled the air. Huge birds walked the shoreline and roosted in the red mangroves lining the coastal trail. In addition, sea lions lumbered on the sand and marine iguanas sunned themselves on rocky tidal pools. Let's talk about booby birds! On expedition, I saw all three Galápagos species. The smallest, the red-footed booby (Sula sula) that, despite its webbed feet, perches on branches. They are fast swimmers and can dive up to 130 feet deep. The Nazca booby (Sula granti), pictured here with a chick, often lays two eggs days apart and one of the hatchlings will kick the weaker one out of the nest. And of course the iconic blue-footed booby (Sula nebouxii)! They look clumsy on land, but they reach speeds of 60mph while dive-bombing for fish. Fun fact: a group of boobies is referred to as a congress, a hatch, or a trap. I for one prefer a "congress of boobies." We saw a Galápagos short-eared owl (Asio flammeus galapagoensis) on a rocky ledge and then later walking across the trail! It is a sub-species of the short-eared owl, a bird which is found on all continents but Antarctica. Most owls hunt at night, yet this owl has adapted to hunt in the day to avoid competition with the Galápagos hawk. Underwater GalapagosThe terrestrial wildlife and the habitats of Galápagos were spectacular, but the underwater world was equally impressive! Although the islands are in the tropics, the Humboldt Current brings cold, nutrient-rich waters to the archipelago, making Galápagos a rich oceanic oasis. In fact, all the iconic species you encounter on land, such as the marine iguanas, sea lions and seabirds, depend on the productivity of the seawater surrounding the islands. Exploring by snorkel at different sites, I was surrounded by thousands of beautiful tropical fish, colorful invertebrates, playful sea lions and graceful green sea turtles. I didn't always capture everything with the GoPro (especially after it died halfway through the voyage), but it will be forever in my memory. Though they were not very active on land, all the sea lions were very acrobatic underwater! Swimming with them was a blast! Anyone else swim towards sharks when snorkeling? I was stoked to get a quick look at this beautiful white tipped reef shark (Triaenodon obesus). Galápagos sharks and hammerhead sharks are also not uncommon, but unfortunately I did not see any. Oh the absolutely magical experience of snorkeling in tropical water and having penguins unexpectedly swim by! This was my favorite moment of the expedition. Adios and GraciasIn 2014, I had the opportunity to voyage through Arctic Svalbard as a National-Geographic-Lindblad Expeditions Grosvenor Teacher Fellow (GTF). Exploring the Galápagos as a GTF Alumna is like having a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Twice. Educator-Explorer friends, please read more about this extraordinary professional development program here.

Overall, as I think back to my time on expedition in Galápagos, I have a strong sense of urgency about protecting this incomparable region of our planet and all its natural and cultural treasures. I am now more aware of how the fragile ecosystems of the Galápagos islands are impacted by tourism and under threat from invasive species and climate change. Sailing as a GTF Alumna was a privilege but also a responsibility; I consider myself an ambassador for the Galápagos islands and will do all I can to educate others. In a future blog post, I will be sharing how I have incorporated my expeditionary learning into my classroom and beyond. I miss our ship the National Geographic Endeavor II and all the incredible crew, naturalists, and fellow travelers. For now, I want to express deep gratitude to leaders at National Geographic Education and Lindblad Expeditions for honoring me with this experience. Also, thank you to all those who made my expedition possible, including my principal, colleagues, and students at the Nueva School. This voyage of discovery is dedicated to them! |

AuthorThis blog contains occasional dispatches from my science classroom and professional learning experiences. Thank you for reading! Archives

December 2021

|

|

Cristina Veresan

Science Educator |

Proudly powered by Weebly

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed