|

Science In The Wild There is no better way to learn about the natural world then to actually go out, get dirty, and explore! Today, all middle school students enjoyed a day of outdoor science learning in Makiki, where they investigated the impacts of climate change in our local environment. This field study was the mauka (mountain) component of our From Mauka to Makai: Understanding Climate Change Impacts in the Ahupua’a program, a partnership with the Hawai'i Nature Center. The program will also consist of classroom lessons, a makai (coastal) field study in February, and student conservation projects in the spring. The environmental educators at Hawai'i Nature Center will help us better understand place-based knowledge in our studies of climate change. Today's mauka investigation was an opportunity for students to explore nature and was a great start to this ambitious program! Oahu's Watershed When you turn on the tap or take a shower, have you thought about where your fresh water comes from? Here on Oahu, all of our water comes from underground sources that originated as rainwater in a process that can take up to 25 years. Our watersheds, areas of land enclosed by mountain ridges, are important because they catch and collect the rainfall to replenish groundwater. The boundaries of the watershed roughly correspond to ahupua'a, the native Hawaiian land division system from mountains to the sea. To begin the process, trade winds drive clouds, laden with evaporated seawater, inland over our island. Next, our mountain ranges, the Waianae and the Ko'olau, trap and force clouds to higher elevations, resulting in condensation and rainfall. A healthy watershed has a plant canopy with trees, shrubs, and ground cover. Together the vegetation in these different layers acts like a giant sponge, allowing water to drip slowly underground and into our streams. If the area is deforested, the rainwater will run off the surface and not seep underground. Finally, in a healthy watershed, this rainwater is filtered and stored underground thanks to the unique geology of the island. As rainwater slowly percolates into the earth, it is naturally filtered by our volcanic soil and stored by dike rock compartments, which overflow and fill the aquifer. Oahu’s aquifer is an underground, natural, freshwater reservoir from which the island's water is extracted for our many uses. Stream Assessment (and fishing!)

The 'O'opu One of the organisms we hoped to see in Makiki Stream was a fish endemic to Hawaiian waters, the ‘o‘opu stream goby. These fish evolved from saltwater goby ancestors. Although ‘o‘opu live in freshwater streams as adults, their fertilized eggs wash downstream, and young ‘o‘opu spend the first several months of their lives in the ocean before they make their way back upstream. Most of the ‘o‘opu species have a very cool adaptation in order to make this journey. Their pelvic fins fuse together to form a suction cup which helps them fasten to rocks, the stream bottom, and even to climb waterfalls. Makiki Stream does not flow uninterrupted down to the sea; it has been channelized and areas of it are diverted through underwater tunnels. These tunnels get incredibly hot and limit the movement of the young ‘o‘opu trying to make it back upstream from the sea. While some streams in Hawai'i have healthy populations of ‘o‘opu, the fish have not been found in Makiki Stream for many years. Climate Change

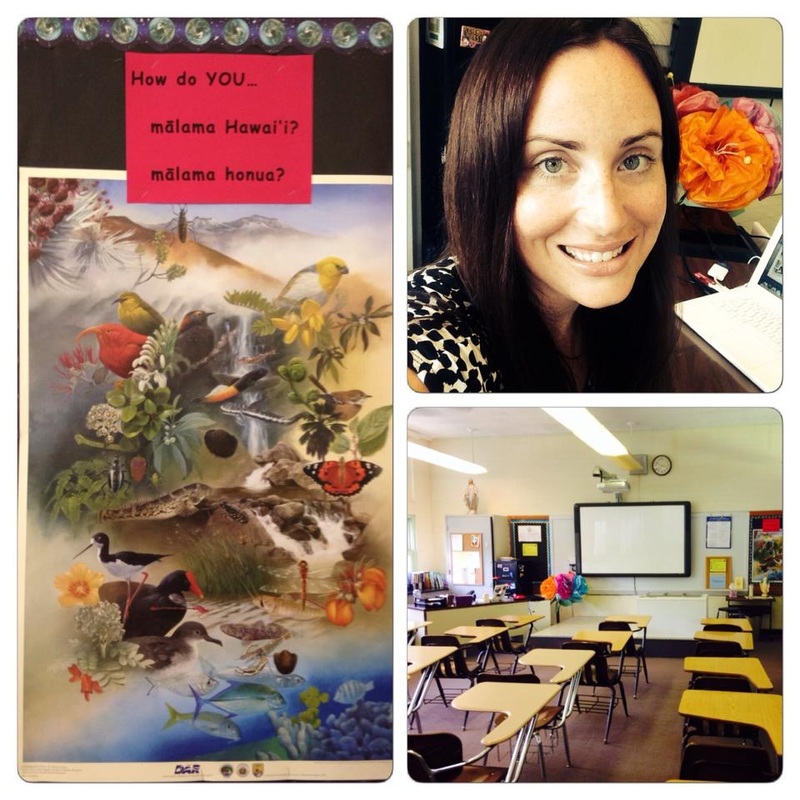

Climate change threatens local ecosystems already degraded by invasive plants and animals, excessive development, and pollution. We know that current climate change is mainly caused by humans burning fossil fuels. Global warming and sea level rise cause very challenging conditions for life on Earth, and islands, like Hawai'i, are particularly vulnerable. Yet there is good news: people can take action to limit global warming and mitigate its effects. Climate change will have some dire consequences here in Hawai'i. Scientists have predicted that, in addition to vast areas of flooding due to sea level rise, Hawai'i will most likely receive less rainfall in the future. Due to increased temperatures, the clouds will increase in elevation and might pass over our island's mountains instead of hitting them. Streams like Makiki will shrink over time. And if there is less rainfall, there is less freshwater to replenish our underground aquifer. We cannot let this happen. In follow-up classroom lessons, students will be investigating ways that they can make choices that help reduce global warming and conserve energy and water resources!  Presenting at the HaSTA annual conference on September 13, 2014. Presenting at the HaSTA annual conference on September 13, 2014. Sharing my expedition learning with students has been most meaningful, but I have also enjoyed telling my story to the larger community of teachers and the public. Today, I had the opportunity to present about my Arctic expedition at the Hawai'i Science Teachers Association (HaSTA) annual conference! I think they'll be some very enthusiastic educators from Hawaii applying to the National Geographic/Lindblad Expeditions Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship Program this year... Message to Science Teachers Here is a link to the Prezi for my session entitled Exploring the Arctic: My Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship. At the start of the talk, I showed a picture of myself in the GTF hat on the deck of the Explorer in the Arctic. I told everyone I would let them know how I ended up on the adventure of a lifetime and how they potentially could as well, through the Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship. I then summarized the GTF Program: expedition travel as professional development for teachers committed to geo-literacy. Next, I explained the National Geographic's three components of geo-literacy, and there was rich discussion about how science teachers can incorporate these components into their curricula. Finally, I got into the details about my expedition, the Land of the Ice Bears, and I explained the characteristics of the Arctic Svalbard region using maps and pictures. I moved through a series of my photographs, highlighting some of the main features of the expedition, including the ship, my shipmates, the landings, the wildlife, and the scenery. Then, I connected my expedition to the larger issue of global climate change as I described lessons learned on my voyage. I explained why Arctic sea ice is so important as critical habitat for wildlife and for regulating global climate, and I shared charts and data that illustrated the recent decline of Arctic sea ice. The “Chasing Ice” trailer was viewed and I described calving events, glacial retreat, and other effects of climate change in the Arctic. I concluded with a summary of how my GTF experience has impacted me and then played my interview from the Video Expedition Report: “it’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity!” Other Community Outreach I am so proud to be an ambassador for National Geographic and Lindblad Expeditions and to help carry their missions forward. For my community outreach, in addition to today's HaSTA presentation, I have leveraged existing partnerships with community organizations, and I have actively sought out new avenues for sharing my experiences. I currently volunteer as an interpreter at the Waikiki Aquarium, and I was able to set up a “learning lunch” slideshow and talk story about my Arctic voyage and the GTF Program. I also volunteer for plankton outreach with Kahi Kai (One Ocean), a local marine conservation group. Before and after my voyage, Kahi Kai published my blog posts. My other outreach activities came as a result of me reaching out to local media. I was able to do pre and post voyage live interviews with our two local news stations KHON2 and KITV4, a live interview on Hawaii Public Radio, an a pre and post voyage print interview with the Midweek. If you haven't yet, you can check out all these interviews on my In the News page! I have applied to present at the 2015 National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) conference in Chicago this spring, and I hope I have the opportunity to attend. Welcome Back! The first day of school at Star of the Sea has come! Welcome to all my new and returning students who are reading this, and I hope you enjoyed your summer break. I am starting this year energized by my summer of education and travel, and I am so excited to share all that I have experienced with you. Now that I have had an incredible voyage of discovery through Arctic Svalbard as a Grosvenor Teacher Fellow, it is my responsibility and privilege to bring back all I have learned. This year, you will have a chance to investigate Arctic ecology, the importance of polar regions, and the impacts of global climate change. We will examine ways in which Hawaii is connected to the Arctic. Get ready for my personal accounts, photos and video from the Arctic! I want to inspire all of you to protect our planet's natural and cultural resources and, hopefully, become explorers yourselves! This year, we will be asking ourselves as individuals and as a society: How do you mālama Hawai'i? How do you mālama honua?

Looking Ahead...

There are quite a few special things to look forward to this year. All middle school students will be conducting science field labs this year for a unique program called From Mauka to Makai: Understanding Climate Change Impacts in the Ahupua’a. This program represents a partnership with Hawaii Nature Center in Makiki, and as part of it, we will be conducting two field studies, one mauka and one makai, and producing a final environmental service project. I also plan to select twenty 7th and 8th graders (by application) to take to the Big Island May 14th-16th for National Geographic's 2015 Bio Blitz. Every year, the Bio Blitz is held at a different National Park, and this year it will be hosted by Volcanoes National Park. The Bio-Blitz is a 24-hour event where teams of students, teachers, rangers, community members, National Geographic staff, and scientists work together to conduct a comprehensive biological survey of the park. That is, they work hard to find and identify as many of the animals, plants, fungi, and other organisms that they can! For more information about the Bio Blitz, please visit this website: www.nationalgeographic.com/explorers/projects/bioblitz/ Mahalo for joining me on a science learning adventure this year! Let's all work together to make sure we have a productive and rewarding experience. 6th Grade Welcome Letter/Course Policies 7th Grade Welcome Letter/Course Policies 8th Grade Welcome Letter/Course Policies Whenever I open up an issue of National Geographic magazine, I immediately flip though the pages to preview the photographs. Though I later return to each article to read the text, the images are most powerful in telling the stories. One of the most exciting aspects of the Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship is the opportunity to learn from the expert photographers associated with National Geographic. I am a totally inexperienced photographer myself and, armed with a hand-me-down Canon Power Shot, was determined to gain some skills. At our pre-voyage workshop in April, naturalists and Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic certified photo instructors Michael S. Nolan and CT Ticknor presented a session on expedition photography that was very inspiring. I was fortunate enough to have both Michael and CT on my Lindblad-National Geographic expedition through Svalbard, where I continued my learning. They both have the technical skill to help the most sophisticated photographers but also the heart to help novices like me. These following expedition photography tips are not my own and must be credited to Michael and CT. However, I will provide my interpretation and examples of my own photos taken on the expedition. Still daunted by settings and white balance, I shot in Auto mode but I did try and pay attention to composition and create images that would help me tell a story. 1. Take an establishing shot. Each landing we made, I tried to take a photo that broadly captured a sense of place--usually with the ship in the background. The establishing shot provided useful context for the other photos. This is a shot of the beautiful isthmus at our last landing. The white sky and muted colors were otherworldly. 2. Leave space in the frame. With the polar bears, it was temping just to zoom in and bulls-eye the animal in every frame. However, when I pulled back and left some space, I got powerful images of the bear in its vast landscape of pack ice. 3. Rule of thirds. When shooting landscapes, think of the frame as divided in horizontal thirds and group elements by thirds instead of halves. So, in this shot of water and sky, instead of half water and half ice, I aimed for two-thirds water and one-third sky. 4. Light sets the mood. Both the midnight sun and the silvery light in the high latitudes were like nothing I have ever seen. I looked for reflections and shadows. I tried to get up at different times, like this shot at 2am, to capture the mood. 5.Get in close. Though I did not have a powerful zoom lens, I did try and get in close where I could. One of the ways I could reasonably do this was by taking macro shots of the vegetation. I often lay down on the spongy tundra to get at ground level. Another way was to zoom in on a glacier face to capture the ice texture. 6. Use continuous shot to capture action. Get to know your continuous shot setting! When capturing action, it is a great way to ensure you don’t miss the look of the arctic fox, the take-off of the guillemot, or in this case, the yawn of the polar bear! 7. Consider the angle of your shot. I tried to get the ship itself and other guests in some of my shots not only for scale and to establish the scene but to find new angles. During a visit by a curious polar bear, I went up a deck to get this shot. 8. Layer your images. I would often hear CT remind us of this when we were on hikes ashore. One easy way to accomplish this is to place something dominant in the foreground with an interesting background like this whale vertebra with hikers and the ship behind it. 9. Get a sense of scale. It can be much more powerful to know how big or how small a subject. After photographing tiny vegetation for several days, it finally occurred to me to occasionally put my finger in the shot for scale! Another example: I took a lot of shots of the bird cliff but this one with the Zodiac in it offers scale. 10. “Don’t Point and Shoot— Aim and Create” This is a motto that Michael and CT shared at our April meeting that resonated for me while on my expedition. I did not want to come back having snapped thousands of pictures but not really capturing the landscape, the wildlife, and my shipmates in a creative way. I am definitely more mindful of how to aim and create interesting images that tell a story. I am inspired to continue my own journey with photography. And one of these days, with a successful Arctic expedition behind me, I might even venture out of Auto mode. All photographs by Cristina Veresan unless otherwise indicated.

Back to Port in Longyearbyen This morning, we ate breakfast, said our goodbyes, and began to disembark the ship. I cannot believe we are leaving the Land of the Ice Bears! It was hard to leave my shipboard home and all my new friends with whom I have shared this great adventure. I have a flight to and overnight in Oslo, a flight to and overnight in Newark, and a long flight to Honolulu before I am back home. Though school is not in session until August, I am already thinking of lessons that draw upon this rich experience. I hope my Arctic adventure will foster a more global perspective, encourage environmental stewardship, and inspire a passion for discovery among my students! Lessons from Svalbard Gaining a sense of place in the high Arctic was a powerful take-away: feeling the tundra sponge beneath my feet on a hike, smelling the freshness of a massive ice cap, hearing the snow bunting sing its solo in the vast Arctic landscape, and seeing a polar bear navigate from ice floe to ice floe in a seemingly endless scramble of sea ice. It was a sparse, harsh, and beautiful environment, and it has left an indelible impression on me. I now have a first-hand experience in the region, and my biggest take-away is not only a sense of place but also a sense of urgency to protect it. I have renewed passion about combating climate change and specifically about conserving our polar regions. In Hawaii and elsewhere in the Pacific islands, negative effects of climate change are already being experienced. I scientifically understood how climate change is a worldwide concern, but my Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic expedition gave me first-hand knowledge of its global reach. As longtime Maui-resident, naturalist CT Ticknor shared in our April workshop, the Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship is a heavy kuleana. Kuleana is a rich, nuanced native Hawaiian word meaning both privilege and responsibility. Now that I have returned from my Arctic voyage, it is my duty to tell the story of my expedition but it is also my honor. Gratitude I feel incredibly fortunate to have been awarded a Lindblad Expeditions-National Geographic Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship. My voyage through Arctic Svalbard has enriched my teaching and changed my life.

Hiking the Arctic Desert It is hard not to mark this day with lasts: Oh, this is our last hike, our last lunch, our last reindeer, etc...But it is a fact that this is our last full day in Svalbard. And I am not ready to leave. This windy morning, the ship entered Bellsund and was finally able to find a suitable anchoring spot so we could go ashore. The staff reported not often landing in this particular place, but I think it was a happy accident. The scenery was breathtaking. Ellen, Aimee, and I had a good long hike in this Arctic desert, and for a last hike, it was amazing.

Guests were piling into Zodiacs and heading back to the ship. As Karen kept watch on the hill for bears, Brian finally got his interviews with Aimee and myself. We had to duck down to get out of the whipping wind. Before he could complete Ellen's interview, Karen announced we had better get going. I think Ellen was relieved! Below is the segment of the VER about the Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship that Brian filmed today. It was difficult to be articulate in a spontaneous interview out in the cold, but I was excited to share my appreciation for the program! Last night on the Explorer... In some ways, Svalbard is exactly as I had pictured and imagined, but my experience has no doubt been full of lovely surprises. Over 60% of the archipelago is glacier-covered, and I certainly have seen plenty of ice in various forms. However, I have also hiked on the spongy green tundra dotted with colorful wildflowers. Svalbard's geology is also quite varied and has rich occurrences of fossils; in fact, there is bedrock from almost every geologic period present here. I was prepared for the cold temperatures but taken aback by the dryness of this climate. People generally associate deserts with heat, but this region is technically an Arctic desert due to lack of precipitation. Arctic deserts are defined as being located above 75 degrees north latitude and receiving less that 10 inches of precipitation annually, an amount comparable to the Sahara. Tonight was also the last nightly recap in the lounge. Lucio explained the disembarkation procedures in detail before our last delicious sit down dinner. People used the shared computers to upload photos from yesterday's polar plunge and share photos for a guest slideshow. Tonight, we enjoyed a bit of social time in the lounge with crew and guests. Aimee, Ellen and I spent time packing and reviewing our journals and photos. Tomorrow our voyage ends where it begins back in Longyearbyen, where the ship will dock and we will disembark. My Lindblad-National Geographic expedition is coming to an end. However, my missions of incorporating all my new learning into my curriculum and of sharing my Arctic story with as wide an audience as possible is just beginning. All photographs by Cristina Veresan unless otherwise indicated.

Read the Lindblad Naturalist Daily Expedition Report (DER) here. A Very Wet Hike Overnight, our ship had begun to retrace its path along the southern coast back to Longyearbyen, and in fine weather, we were able to make a landing after breakfast at Ardalsnuten. This morning's hike made it clear why every staff member I talked to pre voyage stated the most essential piece of expedition gear in two words: rubber boots. Knee high rubber boots are so important because when we go ashore, we travel by Zodiac boats; when we jump out of the boats, it's often into about six inches of frigid Arctic water! Today's hiking conditions were also particularly soggy, and on our long hike, Ellen and I were both thankful we had our rubber boots and waterproof pants. Temperatures had warmed, and there was lots of sunshine and plenty of meltwater. On our wet walk we encountered many bones of the great whales: ribs, vertebrae, and a moss-covered skull. The bones were settled on what was once a beach terrace but is now far from the current shoreline. The earth is slowly rebounding from when it was covered by ice. Svalbard's land, remember, was shaped by glacial activity. This area used to be an important area for early hunters, and we saw a weathered trapper's cabin that had a decrepit beauty. We saw lots of piles of reindeer scat but only a few actual reindeer. I had hoped we would be approached by reindeer, for I have not yet had a close encounter. A Polar Plunge!

Climate Change in the Arctic Lindblad Expeditions provides guests high quality, engaging interpretation through its naturalist staff during voyages. Additionally, they invite a Global Perspectives Guest Speaker familiar with the region to explore with guests and provide informal and formal commentary. On our expedition, we were fortunate to have polar ecologist Dr. Andrew Clarke with us to share insight into climate change and its impacts in the polar regions. This afternoon, as we cruised across Storfjorden, headed for the southernmost tip of Spitsbergen, Dr. Clarke gave a compelling lecture in the lounge. He made sure to distinguish between climate and weather at the start of his talk. Weather refers to short term conditions while climate reflects the long term average conditions for a region. Simply put: climate is what you expect, weather is what you get. Dr. Clarke outlined how our modern climate is not what we would expect. That is, our global climate is experiencing a pronounced warming trend beyond the range of natural variability. Sea levels have risen in the last century. And the scientific consensus is that the major cause is an increase in atmospheric CO2, predominantly due to the burning of fossil fuels. Climate change is real; let's not debate it's existence, let's work on solutions. The effects of climate change in the Arctic are quite dramatic. Data presented indicated that the Arctic is warming rapidly, ice is forming later and melting faster, and the melting surface layer of the permafrost is getting deeper. I thought of the underweight polar bear we had seen. The glacier calving we witnessed. The tidewater glaciers with newly exposed land beneath them, evidence of retreating. This Arctic ecosystem is threatened, and I have a newfound sense of urgency to protect it. I have observed evidence of climate change in Hawaii and now more evidence on the other side of the world. Global change is truly an issue that connects us all. But combating it can, too! Fin Whales Later in the afternoon, the weather turned cold and the wind picked up a bit. Just before our evening recap, two fin whales were spotted and the captain positioned the ship closer to them. The two whales were feeding and surfaced periodically to breathe. There's something so powerful about being in the presence of great whales. So much of the animal is unseen under the surface but you can sense it's immensity. It was difficult to get a great photograph, but the experience is unforgettable and, like many times on this voyage, I just tried to be fully present and enjoy the moment. I was one level up from the bow and it was fun to watch everyone move from port to starboard and back again, shutters clicking, as the whales silently repositioned themselves underwater. Yes, the wind has picked up and we are getting a lot of ocean motion tonight. After another fabulous dinner, everyone gathered in the lounge for a preview of our Video Expedition Report (VER). On each Lindblad Expeditions voyage, an expert videographer shoots the amazing moments along the way and by the end of the expedition, presents a complete, edited short documentary VER. Talented artist and adventurer Brian Christensen joined us on our Svalbard expedition and created our VER. As I expected, he beautifully captured the stunning scenery, documented diverse wildlife, and conducted interviews with guests and naturalists. Goodbye to another awesome day in Svalbard! All photographs by Cristina Veresan unless otherwise indicated.

Read the Lindblad Naturalist Daily Expedition Report (DER) here. The Bird Cliff at Kapp Fanshawe I hate to admit this, as curious as I am about the natural world, I have never really considered myself a bird person. I have a tough time using binoculars, and I feel like I can never see what birders get that excited about-- literally. Unless it's a big wading bird, I cannot even get a good look and certainly not a good picture. My Mentor Naturalist Karen talks about birds with such passion, though. When I see her on the bridge early this morning, she tells me, "We saw an ivory gull!" and I want to share her excitement as she relates how these birds often follow bears to scavenge their kills. When another naturalist explains how the little Arctic tern migrates from the high Arctic all the way down to Antarctica and back again in a year, I can appreciate this record-breaking accomplishment. And when I am hiking out on the tundra, I love straining to hear the snow bunting sing out its solo tune. But birds still leave me feeling kind of ambivalent. That all changed at the Kapp Fanshawe bird cliffs. I dare anyone to spend some time cruising right below these towering cliffs crammed with a quarter million nesting murres and not be in complete awe of bird life. That's how I spent this morning. Once we sailed out of Bear Sound and through the Hinlopen Strait, we had made our way to this amazing point of land in Eastern Spitsbergen. As we approached the cliffs, I was dwarfed by the sheer rock cliffs rising hundreds of feet from the sea lined with shoulder-to-shoulder murres. I was deafened by bird noise. Oh, and did I mention the acrid guano smell?

That is, until the chicks are ready to leave the nest. At this point, usually at night, the father will call the chick down from the ledge for what might be a free fall into the sea. Selection at work! Surviving chicks swim away with their father, and he continues to provide food for them as they develop. I took my attention away from the cliffs for a second and looked down at the sea. There were a few ice floes that shone white above the water but glowed with a blue hue below the surface. Suddenly, two of the ice floes began moving. Fast. I turned to naturalist Doug Gualtieri, pointed down, and (foolishly) asked "Doug, why is that ice moving?"

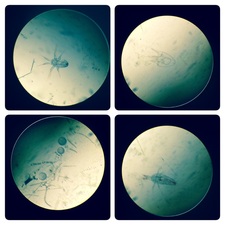

Plank-ton of fun! I participate in plankton outreach with a local non-profit back in Hawaii, Kahi Kai ('one ocean' in native Hawaiian). For my voyage, they have given me a unique tool we use in our outreach for mobile microscopy: the Cell Scope. The Cell Scope contains powerful optics but easily connects to an iPhone in order to observe and photograph plankton. I facilitate an annual plankton lab with my students at Star of the Sea, but I never imagined I would get the chance to do one in the high Arctic! As excited as I am to observe the macro life up here in the Arctic, I am also interested in the micro life drifting undetected in these frigid waters. The base of this Arctic food chain, tiny plankton, was on my mind, and today I finally got a chance to conduct a plankton tow. The first officer Piers took me out in a Zodiac after shuttling guests, including Ellen, to shore for a hike. With us were Aimee to observe and photographer Sisse Brimberg to capture the action. The plankton net is a funnel shaped, fine-meshed net connected to a plastic bottle. When the plankton net is towed through the water for awhile, you get a concentrated sample of plankton in the bottle. As we cruised by Idunbreen glacier and I gripped the tow line as the plankton net streamed behind us in the icy water. Enjoy this slideshow of plankton tow images taken by the amazing Sisse Brimberg, and graciously provided to me for use on my blog. When I got back aboard the Explorer, I could see lots of organic matter suspended in the sample and, thankfully, some swimming plankton! I took a cursory look at my sample in the Zodiac landing area but quickly realized I needed to find a more suitable spot. So I took my sample and the Cell Scope up to the Observation Deck where I could interact with guests and enjoy the majestic alpine scenery. Over and over, I used a plastic dropper to draw up a small amount of water to put on a slide, put the slide on the Cell Scope, and tried to find as much plankton as possible. I was happy to explain to guests what I was doing and share my passion for plankton. Some guests put their iPhones in the Cell Scope and attempted to find and photograph plankton themselves. I let them know that we all depend on plankton not only for supporting marine food chains but also for the oxygen they release during photosynthesis. Considering how much of the Earth is covered with seawater, does it surprise you that plant plankton provide us with about 60% of the oxygen we breathe?

While I was playing with Plankton... Ellen had a fantastic hike on the rocky coast adjacent to Idunbreen Glacier and shared these images with me. Lindblad Expeditions provides guests the opportunity to explore pristine and remote places, and the company is guided by a strict set of Governing Principles that really sets them apart in their field. The principles outline the commitment to guest safety and the high level of service. But one that really sticks out for me is "Positively impact the areas we explore and in which we work." One of the ways we do that is to leave only footprints and take only photographs. When we are ashore, we do not take anything with us: artifacts, fossils, rocks, specimens, bones etc...However, Ellen's hiking group made an exception to the no-take rule when they cleaned a small area of plastic trash. Now that's a positive impact! Another Bear!

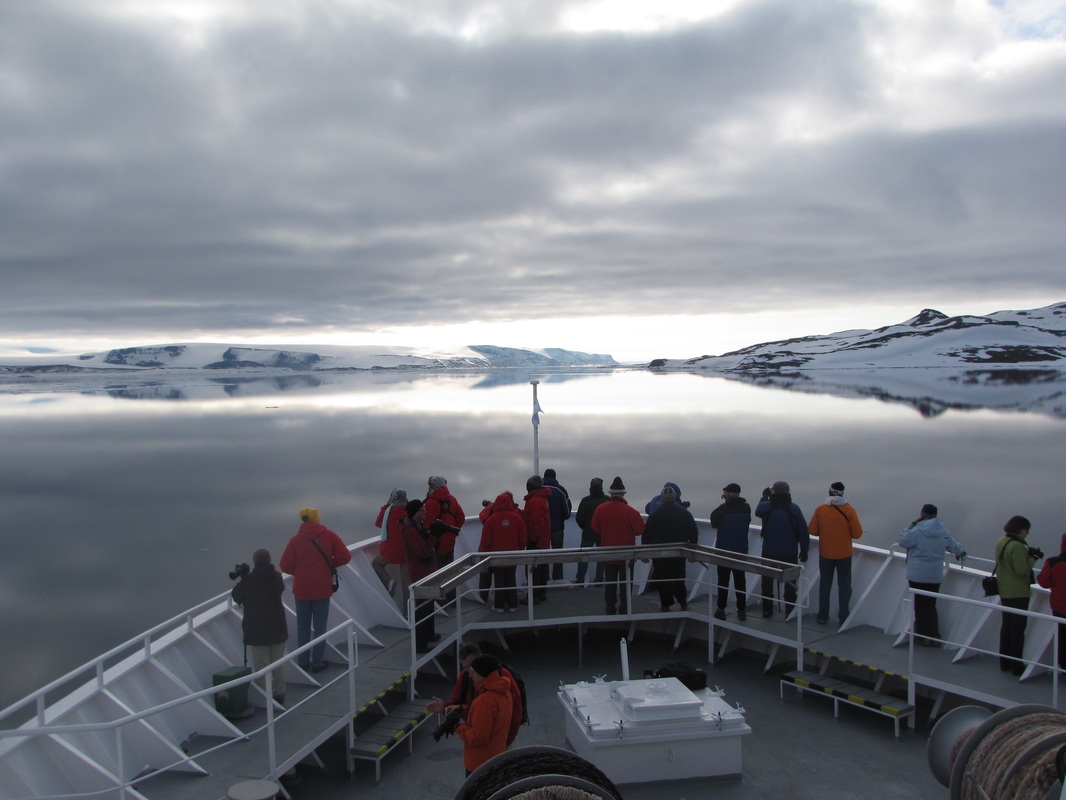

It was an awesome experience to once again observe a polar bear in its natural habitat. This large male bear appeared healthy and fat. We watched him walk across the ice with his huge paws, stopping every once and awhile to look up at our ship. Often, polar bears will roll on the ground after they swim to get the salt off them. But this bear in one amazing moment sprawled out on his belly! He came near the ship only once before lumbering away. I got thinking about a lecture that Magnus had given about polar bears. Polar bears diverged from brown bears in their evolution about 300,000-500,000 years ago and have adapted to their extreme conditions in both physical and metabolic characteristics. Because polar bears and brown bears can mate, there has been discussion in the scientific community about whether or not they are each different species, but recent genomic evidence confirms they are in fact unique species that have intermingled and interbred at various times. In fact, Magnus reported that due to climate change causing habitat to overlap, brown bears are again mating with polar bears in some parts of the world, and a few hybrid bears had been identified. The Day Winds Down... The silvery light in the high latitudes continues to amaze me. A group of us is gathered on the bow, taking in the scenery. When the water is this calm, the light so silvery, and the sky this full of wispy clouds, is it even possible to take a bad photograph? Gorgeous subject matter. I try not to think about the days of my voyage counting down, for I do not want this experience to end. Life aboard a ship has a sense of shared initiative and camaraderie like nothing else, and this ship is filled with such capable, fun, and interesting shipmates. Two of them are in my cabin right now. Aimee and Ellen are having another rich discussion tonight, dissecting our day and brainstorming all the ways we can incorporate our new learning into our curriculum. Oh, and there also might have also been some girl talk. All photographs by Cristina Veresan unless otherwise indicated.

Read the Lindblad Naturalist Daily Expedition Report (DER) here. Cruising the Pack Ice...

In the bridge, expedition leader Bud and first officer Piers studied the most recent ice charts in order to plan our day. Naturalists and crew scanned the horizon with their binoculars. Yes, today will be spent cruising in and along the pack ice looking for wildlife and taking in the icy scenery. Before lunch, there was also a presentation on Svalbard's natural and cultural history by naturalist Carl Erik Kilander. His presentation outlined the human uses of Svalbard in the 1600-1800's and their impacts on the wildlife: from the Dutch whalers who decimated populations of the blue and bowhead whales to the Russian hunters that would spend all winter hunting and trapping polar bear, arctic fox, birds, and reindeer. He spoke about the rise of coal mining and founding of Longyearbyen, and the fact that mining is currently being phased out and replaced by tourism and scientific research. 98% of Svalbard is wilderness, making it one of the world's last great wild places, and 65% of it is completely protected. Conservation of wildlife and habitat has allowed the Arctic animals of Svalbard to thrive in recent years. However, Svalbard's ecosystems are still vulnerable to more long-range threats like global climate change, radioactivity and other pollutants, and resource depletion and mismanagement in the Barents Sea. Carl Erik's talk was not only concerned with the history but also with future of this region he loves so much. Seals, Seals, Seals! It was a great day for pinnipeds (seals)! The two seals that make up the bulk of a polar bear's diet are ringed seals (Pusa hispida hispida) and bearded seals (Erignathus barbarous), and we were fortunate enough to see both species today. The ringed seal gets its name from the spots that mottle their light brown coats. And the bearded seal is named for its long, white whiskers used to feel for prey on the muddy sea bottom (this feeding behavior also gives its face a characteristic coppery hue). Both seals have thick layers of blubber to insulate themselves from the cold and thick nails on their flippers to grip the ice when resting. They are streamlined, fast swimmers and can usually evade polar bears when underwater. On the ice, however, they are vulnerable to attack. The photos below represent two different survival strategies of the seals that naturalist Michael Nolan shared with me. The smaller ringed seals are generally found in the center of large ice floes, next to their breathing holes. For a polar bear to attack, it would have to pull itself up on the far edge of a floe and run across the ice. The ringed seal would hear the bear and be able to quickly slip down the hole and swim away. The only danger would be when the seal returns to its hole, perhaps after hunting some fish, and can be surprised by a waiting bear. It is said that polar bears can even smell which breathing holes are most frequented. The larger bearded seals most often hang out on the edges of smaller ice floes, looking downward to keep watch for predators. They keep to the edge so they can quickly roll into the water if there is any sign of a bear. Once in the water, the bearded seal can swim away, provided the seal has reacted quickly enough. The relationship between seals and polar bears is, as Michael told me, a dance over time of each species trying to outwit the other. Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) are seals that do not often fall prey to polar bears, for males and females have ivory tusks with which to defend themselves! Our excellent spotters saw a walrus on a far off floe, and we cruised closer to get a good look. These large seals can weigh up to two tons! We got close enough to see the vibrissae (whiskers) lining its snout. The whiskers are used to search out invertebrates like clams and sea cucumbers from the muddy sea bottom. Sometimes walrus haul out on land and pile in large groups in order to retain heat and protect their young from the ice bears. But this walrus was all alone on a small ice floe. Ice Caps and Grosvenor Teacher Fellow Hats This afternoon, the ship made its way to Austfonna, a formidable tidewater glacier that is actually the third largest ice cap in the world by area (after ones in Antarctica and Greenland). The total area is over 3000 square miles! The sheer face above water is incredible, but most of the ice is underwater. We learn that it is about 1800 feet thick in places, though on average about 900 feet thick. As we approached the face of the massive ice cap, Ellen, Aimee, and I were humbled by its beauty. The air was incredibly fresh and we swore we could hear the ice pop and tremble. On the ice face, the creamy white glazed over the vibrant blues like a confection. The slideshow below has some great shots of the Austfonna ice cap...and us Grosvenor Teacher Fellows rockin' our GTF hats!

Enjoy this slideshow of Austfonna portraits of the Grosvenor Teacher Fellows taken by the amazing Sisse Brimberg, and graciously provided to me for use on my blog. Breakthroughs and Reflection This evening, we cruised by the edge of the last remaining fast ice in Bjornsundet. There were times when the Explorer had to ram drifting pack in order to push forward. It was so cool to watch from the bow as the ship broke through. Alone on deck, I looked out at the fractured surface of the sea and reflected on the ice. Birds dipped and dived in our wake, for we had uncovered food sources below. All Arctic life truly depends on the ice to survive: these birds, the seals we saw today, and the polar bear we had observed yesterday. The high Arctic is a place of relatively simple beauty. Of breakthroughs and reflection. All photographs by Cristina Veresan unless otherwise indicated.

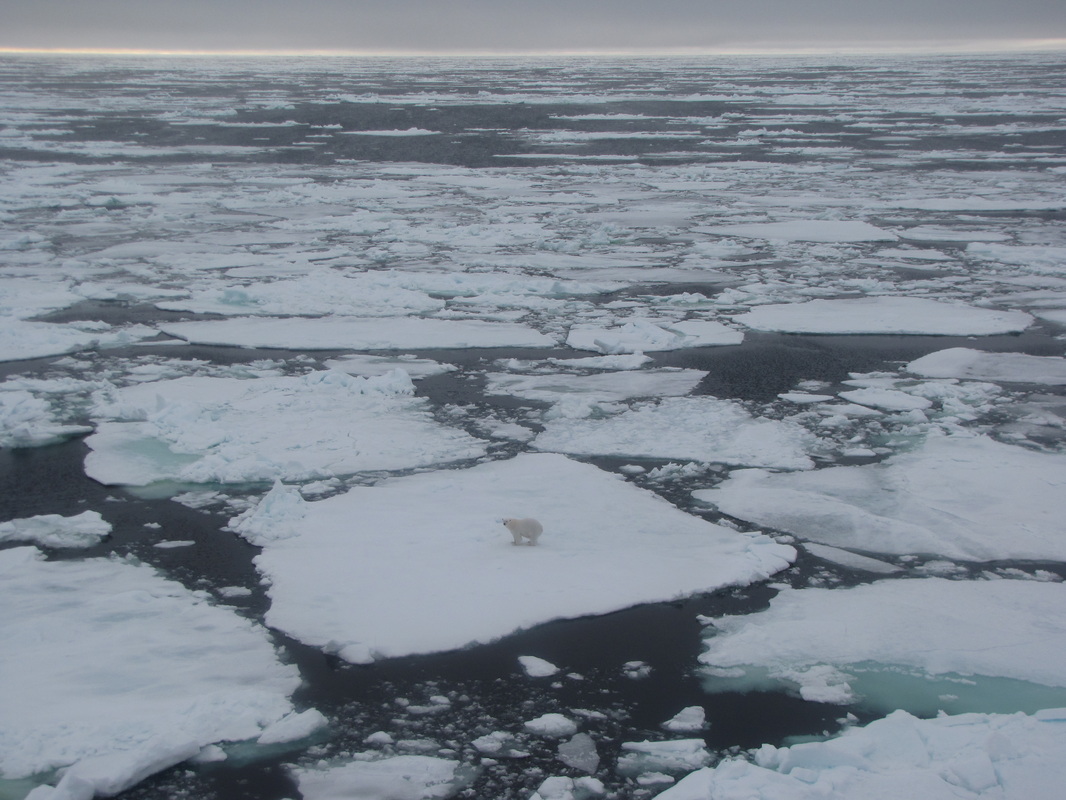

Read the Lindblad Naturalist Daily Expedition Report (DER) here. A Morning Kayak  What a team! Photograph by Piers Alvarez What a team! Photograph by Piers Alvarez After another sleepless night, my morning coffee on the bridge, and breakfast with my fellow Fellows and our naturalist mentor Karen Copeland, I was ready for a morning excursion! We were anchored at Rosenbergdallen, a broad valley at the northwestern corner of Edgoya island. Hikes promised to be quite scenic with the chance of reindeer encounters. However, the waters were calm enough for kayaking, and I could not pass up the chance to paddle in the high Arctic. Ellen decided she wanted to hike, but Aimee was game to share a kayak with me. It was amazing to be inches above near-freezing water in our kayak. I had on enough layers to keep me warm, though I felt a bit awkward holding my paddle with thick gloves. There was not much wind, and the frigid water was quite glassy. Aimee and I enjoyed the vast Arctic scenery as our paddle blades sliced through the still water and propelled us forward in a wordless rhythm. On the gentle slopes of Rosenbergdallen, was both snow, melting with summer's warmer temperatures, and swaths of tundra vegetation. Reindeer ambled along the hillsides, stopping to feed on new grasses. An Accidental Nap After lunch, the ship began making the passage between Barentsoya and Edgoya, and I spent some time talking to guests up on the observation deck. In the late afternoon, I retreated to my cabin to do some journaling. However, as soon as I was in my bunk, I fell fast asleep! Sleep, which had eluded me for two nights, had finally arrived and my body shut down. In fact, I slept through dinner but awoke soon after. Ellen had just crept into my bunk with a plated sandwich for me when the intercom crackled and Bud's soothing voice announced, "For those of you who might not have heard, a polar bear has been spotted. You'll want to make your way up on deck." Ellen and I frantically donned our coats, neck gaiters, hats, gloves, and cameras. Yes, I needed some sleep, but this was worth waking up for! Leader of the Pack (Ice) Most guests shared with me that the reason they chose this particular expedition was to see the polar bear/ice bear in its natural habitat. The prospect of observing this iconic Arctic animal was thrilling to me as well, but I knew that there was no guarantee. Arctic wildlife is very spread out, especially the polar bears, and our experienced staff and crew was working so hard to spot them. The bear we had seen at a distance the other day foraging seaweed was so underweight, and I hoped that this bear would be more healthy. I stepped out on deck on the port side and looked out. It was truly like I had woken up in a different world. In every direction, ice floes of all sizes dotted the sea surface like scrambled white puzzle pieces. I crossed to the starboard side and looked down. An ice bear looked up at me and I was too stunned to grab my camera. The bear's dark eyes held my gaze for a moment and then scanned the ship. By now, the bow below was filled with guests, who pointed lenses of all sizes at the bear. Our ship was not moving, but I watched as the bear moved closer to us. This bear was curious! For the better part of an hour, we were able to observe this bear. The naturalists explained that she was most likely a younger female who had not seen a ship before. It was one of the greatest joys of my life watching the bear behavior: rolling around in the snow, hugging a chunk of ice, yawning, and jumping in and out of the water in between floes. People stared in reverence, silent except for their camera shutters clicking. Mine was clicking, too; here are some of many images captured of this beautiful animal.

This bear appeared fat and healthy. Eating mainly a diet of blubber-rich seals and occasionally walrus, beluga whale, great whale carcasses, and even birds/bird eggs, polar bears are top predators in their environment. They can weigh up to 1500 pounds and up to 50% of their body weight comes from fat. These carnivores get their water from the chemical reaction that breaks down fat, so they do not even need to drink water. This polar bear's coat appeared bright white, though a yellowish coat is most common. This color obviously camouflages the animal on the ice, and I can attest that the bears are very difficult to spot! The hair follicles of the coat are actually clear and hollow. Hollow fur transmits the sunlight (much like a fiber optic thread conducts light) to the black skin underneath, where it is absorbed as heat. Polar bears do not hibernate, but they are able to adjust their metabolic rates depending on the availability of food. However, female bears do slow down for pregnancy, birth, and nursing in the cozy confines of a winter den they dig in the snow. Generally, females mate on the ice during the early spring but can delay implantation until they successfully den. Perhaps this female bear has already mated and will give birth in the winter. Maybe, as the sunlight returns, she will nudge her cubs, now large enough to trek, out of the den and begin teaching them about life on the ice and how to hunt seals. I can only hope this and other bears continue to have the ice they need. Their survival depends on it. What an incredible day! Though my expedition doesn't seem that long on a calendar, my time is filled with so much learning (and light) that days seem to last longer than expected. Amazingly, after my nap, I still get some sleep at night. And I am pretty sure I had some Arctic dreams...

All photographs by Cristina Veresan unless otherwise indicated. Read the Lindblad Naturalist Daily Expedition Report (DER) here. |

AuthorThis blog contains occasional dispatches from my science classroom and professional learning experiences. Thank you for reading! Archives

December 2021

|

|

Cristina Veresan

Science Educator |

Proudly powered by Weebly

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed