|

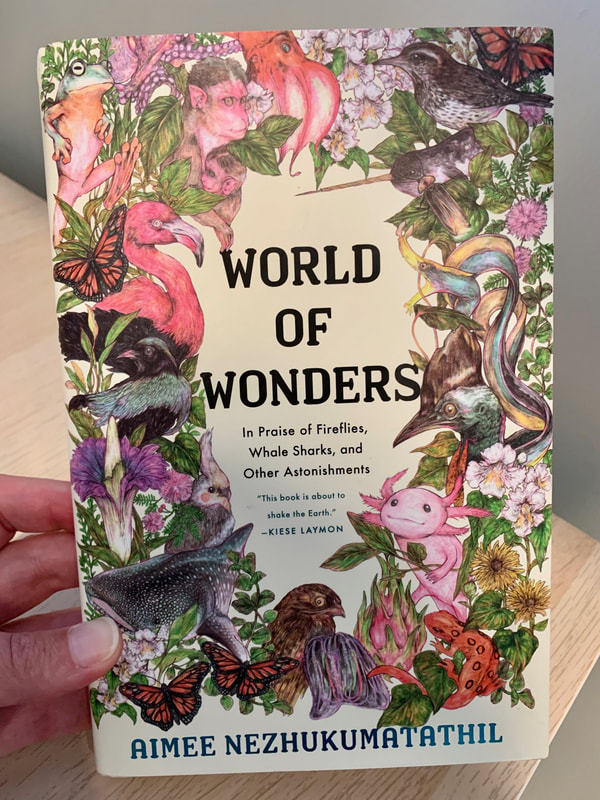

Our topography and coastal climate make the Bay Area a biodiversity hotspot- meaning not only that it supports a rich variety of plant communities and wildlife but also that the ecosystems are under threat. Despite widespread development, our region is home to hundreds of native plant species and a dazzling array of birds, mammals, amphibians, and reptiles. Many species are endemic— found nowhere else in the world— and some have been classified as rare and endangered. I think a lot about how I can help my 5th grade students gain a sense of place and nurture a deep appreciation for our local biological diversity. This year, a new way I've addressed that in my curriculum is through Bay Area Wonders, a project that was developed as a collaboration with my colleague— Nueva School writing teacher Cliff Burke. We were both inspired when we saw writer Aimee Nezhukumatathil speak at our school's Humanities Fair last year; even over Zoom, Nezhukumatathil sparkled with enthusiasm, and her insights about her writing process and the natural world were equally impressive.

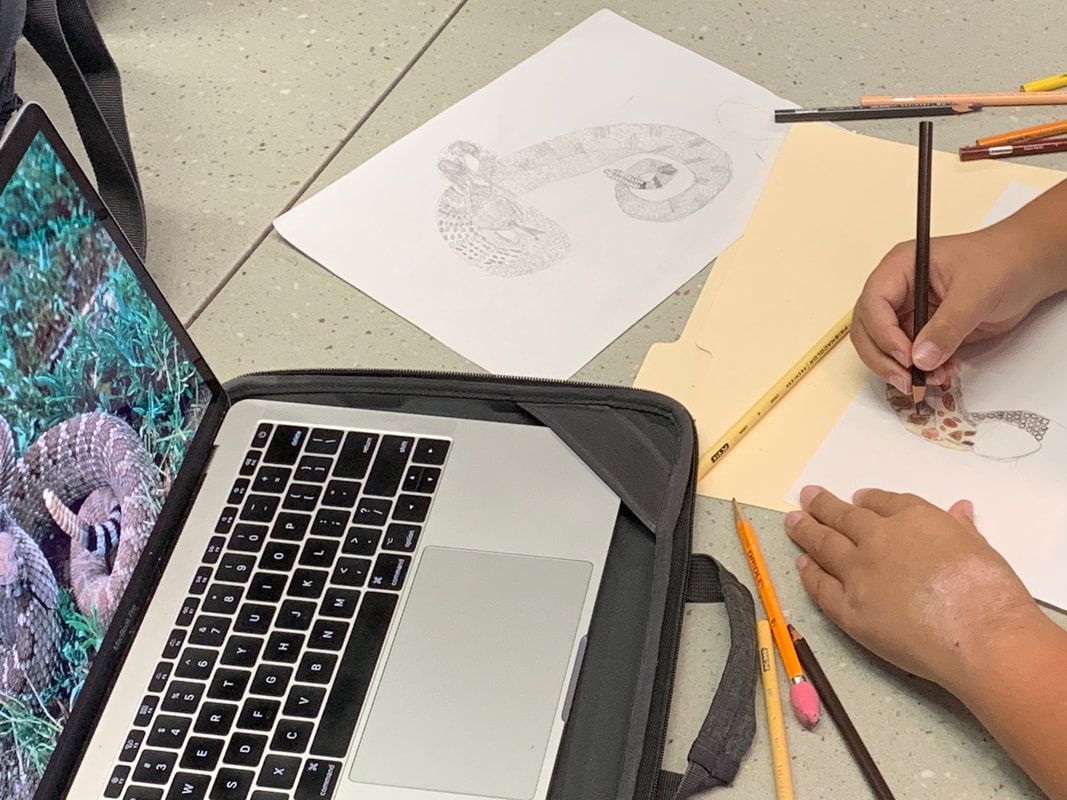

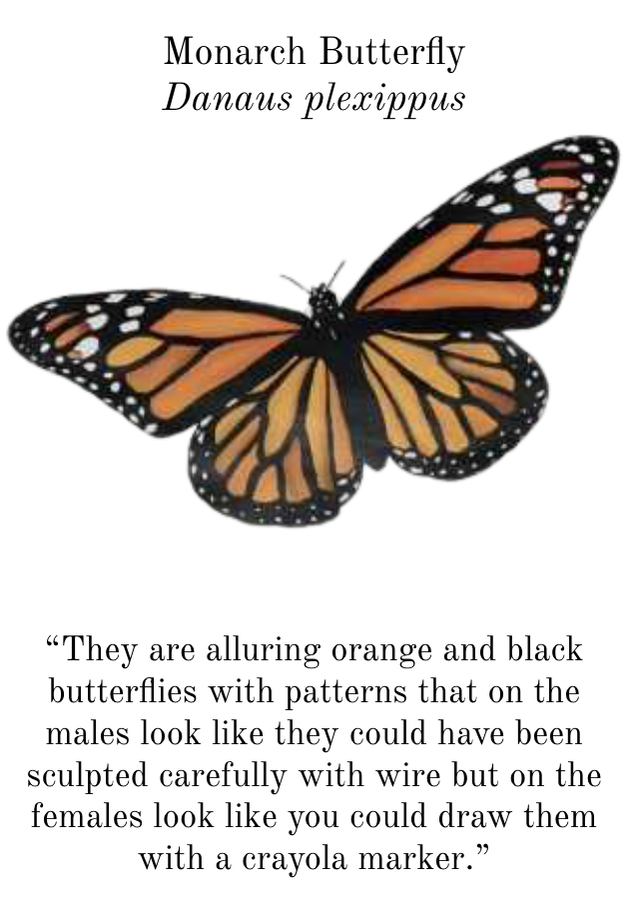

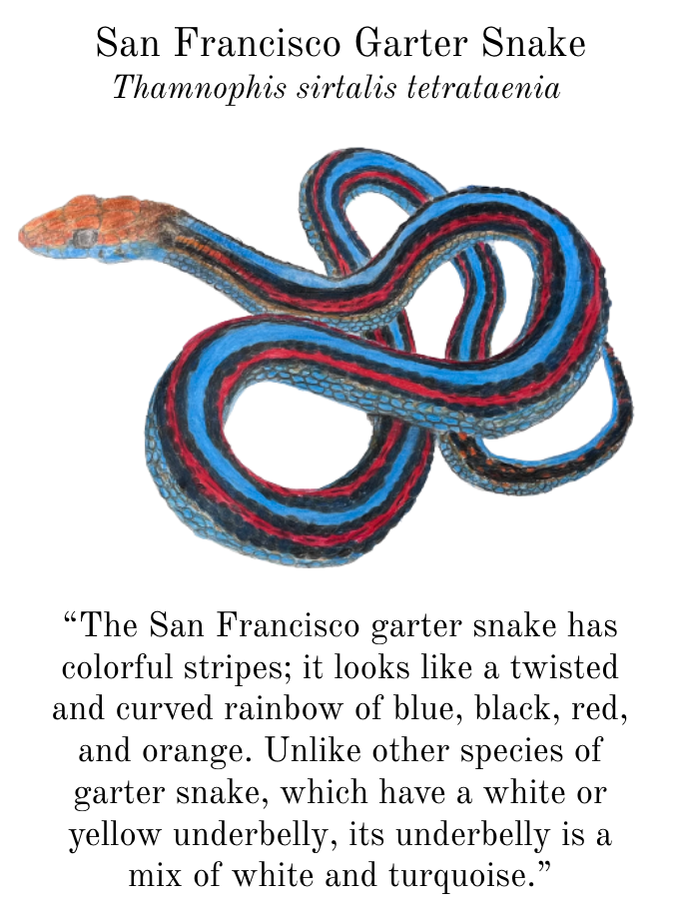

For our project, we decided to keep a local focus. Students were provided a curated list of Bay Area native plants and animals to choose from, but they were also free to select a species they found on their own. We encouraged students to choose a species with which they felt connected; for some, they had observed an organism first hand, while for others they just related to an aspect of the organism's physical characteristics or behavior. So a student might feel connected to a humpback whale because they saw one breaching on a whale-watching trip or they might feel an affinity towards a mountain lion, having never encountered one, due to its speed and agility. In science class with me, students investigated ecology concepts while in writing class with Cliff, they read and analyzed essays from World of Wonders. One great resource we found to help introduce the project to students is the Science Friday segment It's Still A Wild, Wonder-Filled World. Then, using Nezhukumatathil's essays as a guide, students researched and wrote their own essay about their selected species— combining personal experiences with observations and natural history information.

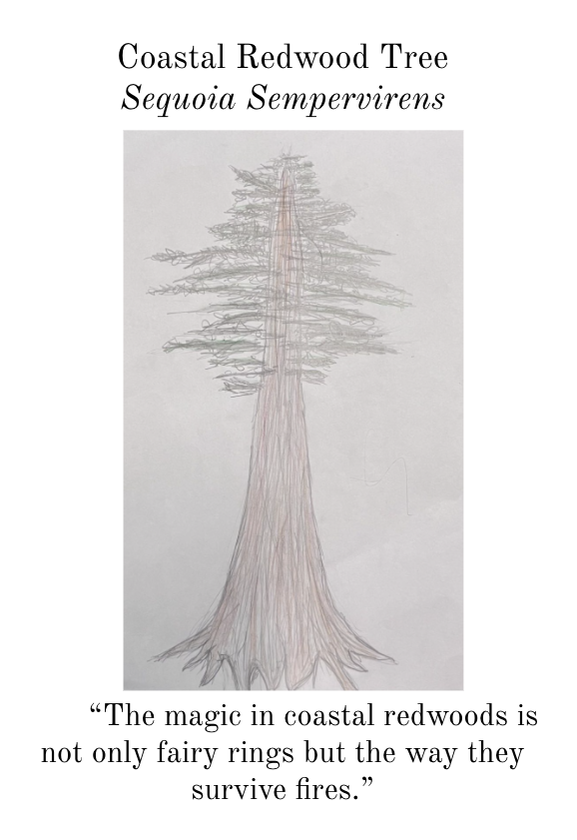

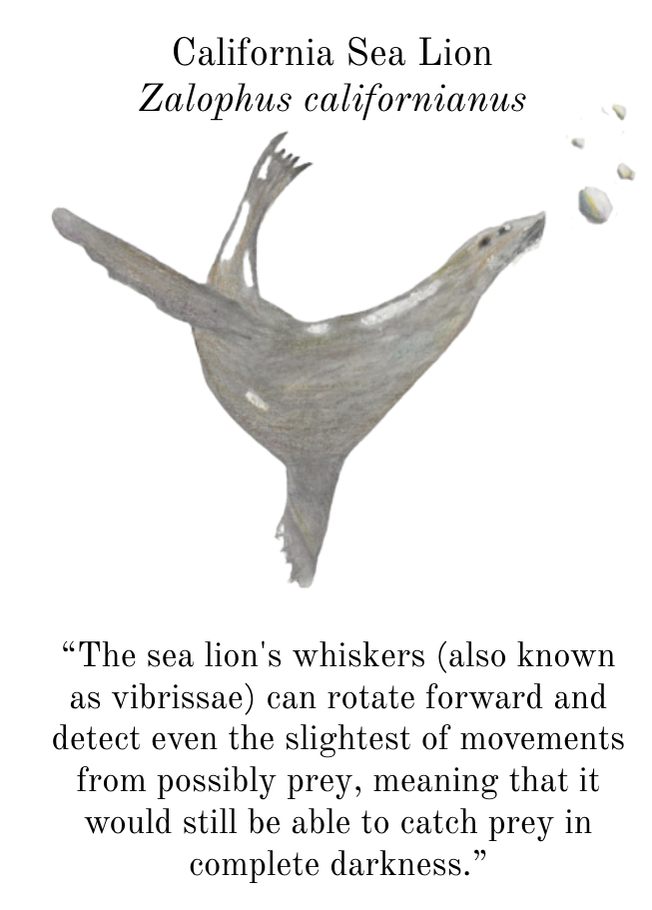

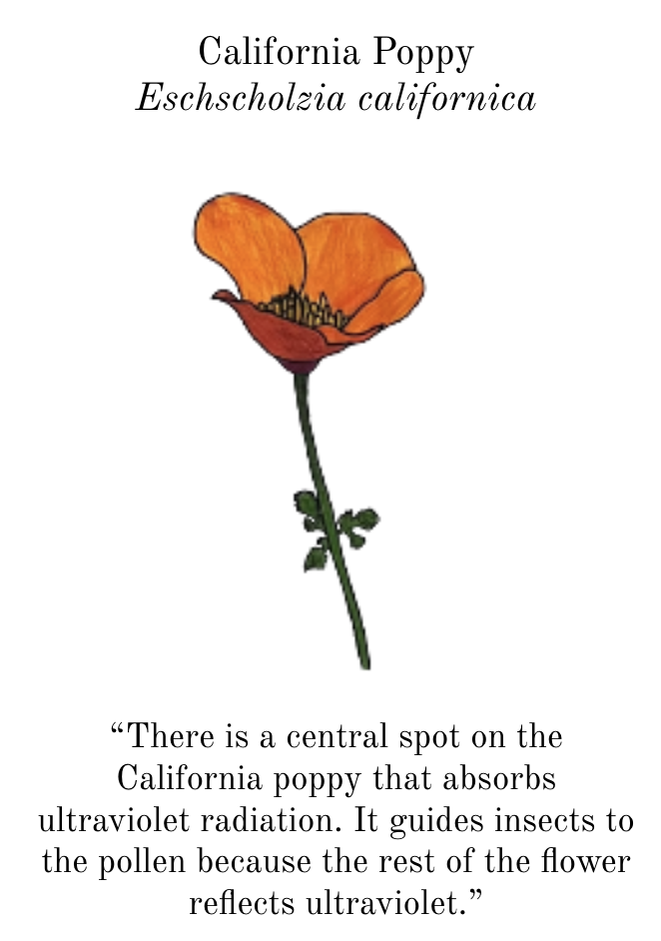

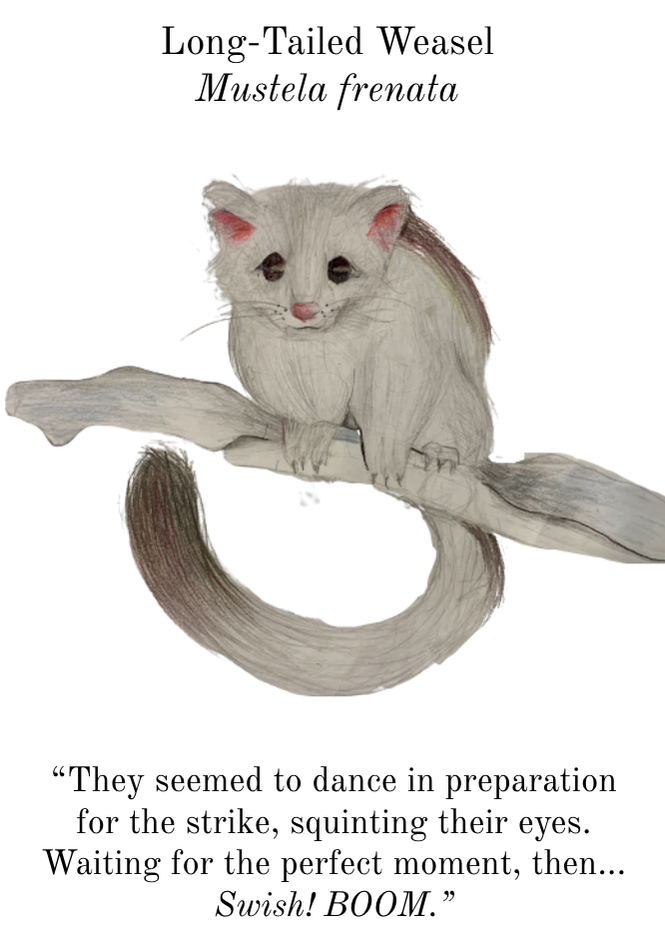

Here is a gallery of featuring some of the amazing scientific illustrations and essay quotes. All the 5th grade essays were anthologized in a Bay Area Wonders collection you can view here. The book was expertly formatted by LiAnn Yim from the Nueva School's Communications team. All students received a beautifully bound copy of the book; hopefully, families will treasure this celebration of local biodiversity!

I was excited to develop and teach a weeklong Coral Reef Adventure course for Nueva Summer this year! During the remote class, students were immersed in the most biodiverse marine ecosystem on Earth— the coral reef. Through activities like engineering a coral polyp out of household items and virtually diving the extraordinary reefs of Palau, students explored the fundamentals of coral reef ecology.

Coral Polyp-Palooza

Tiny zooxanthellae algae live within the tissues of the polyp. Corals provide the zooxanthellae with a protected home and the coral's waste gives energy to the zooxanthellae. Through the process of photosynthesis, the zooxanthellae produce food for the coral. Since they both benefit from each other, the symbiotic relationship is referred to as mutualism.

3D Corals & Coral BleachingWhile our polyps were delightful, it's also an option to 3D print durable physical models of polyps or entire colonies. 3D models of actual coral specimens can be made using a technique called photogrammetry to “capture” corals in three dimensions. In the process, multiple 2D photographs of a coral taken from different angles are combined into one 3D digital model using custom computer software. Models can be created through photogrammetry of both living corals underwater and preserved specimens in a museum. These types of models can be made for scientific study, museum exhibits, education, aquariums, or just for fun! Non-profit organization called The Hydrous, committed to connecting people to the ocean through technology, has a diverse gallery of digital coral models (see them on SketchFab). Once you have a digital model of a coral, it can be easily 3D printed.

Once the coral model's paint was completely dry, I was ready to test it. I placed the model in warm water to simulate coral bleaching - the phenomenon that is causing the rapid decline of coral reefs. In an actual coral, as water temperature increases, zooxanthellae leave the coral and it turns white (or appears to “bleach”). It's a total breakdown of the symbiotic relationship between the coral and its zooxanthellae. Students were amazed by the visual transformation— see it yourself in the short video below. This demonstration could be replicated with your own 3D printed coral models of various species. The models could also be used in the classroom as the basis for student investigations or for a high-impact demo in a STEM fair or other science outreach event. All actual corals have bleaching thresholds, the temperature at which they will bleach, and this varies by species, shape, location, and a number of other factors. Sometimes, if conditions improve, zooxanthellae will repopulate and the coral will ultimately survive. Most often, though, a bleached coral will die. Thus, coral bleaching events due to climate change are a major threat to coral reef ecosystems worldwide. Virtual DiveOur course culminated with a virtual reality (VR) dive through the spectacular reefs of Palau! All week in our Zooms, students had practiced the SCUBA diving hand signals to communicate their status (ok? distressed?) and to indicate the presence of reef creatures like octopus, sharks, and sea turtles. On dive day, students donned VR viewers and got to submerge into an underwater world. During the dive, students felt like they were really underwater and could look in all directions to explore their surroundings - they even put the hand signals to use! I'm grateful that my friend Dr. Erika Woolsey, The Hydrous CEO and National Geographic Explorer, could arrange for ambassadors Andrea and Will to help us out. The dive itself is 360-degree VR movie titled The Hydrous Presents: Immerse. It beautifully recreates what it’s like to SCUBA dive, whether you're watching a huge manta ray glide overhead or looking down at the intricate and colorful reef below. The movie takes you on an underwater tour led by Dr. Woolsey and narrated by other marine scientists and young ocean advocates. Get your own preferred VR viewer- like this inexpensive Google Cardboard- and check out the film on YouTube! Additional ResourcesDo you want to go deeper? To continue your own coral reef adventure, here is a curated list of some resources for learners of all ages:

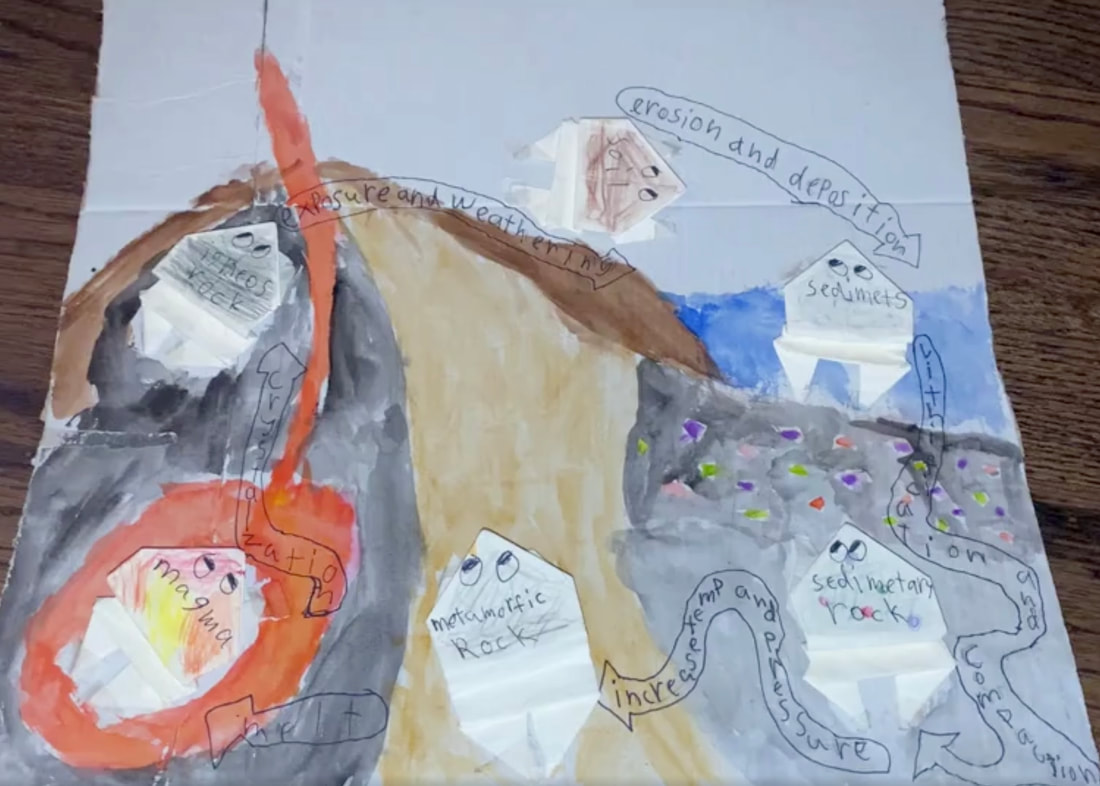

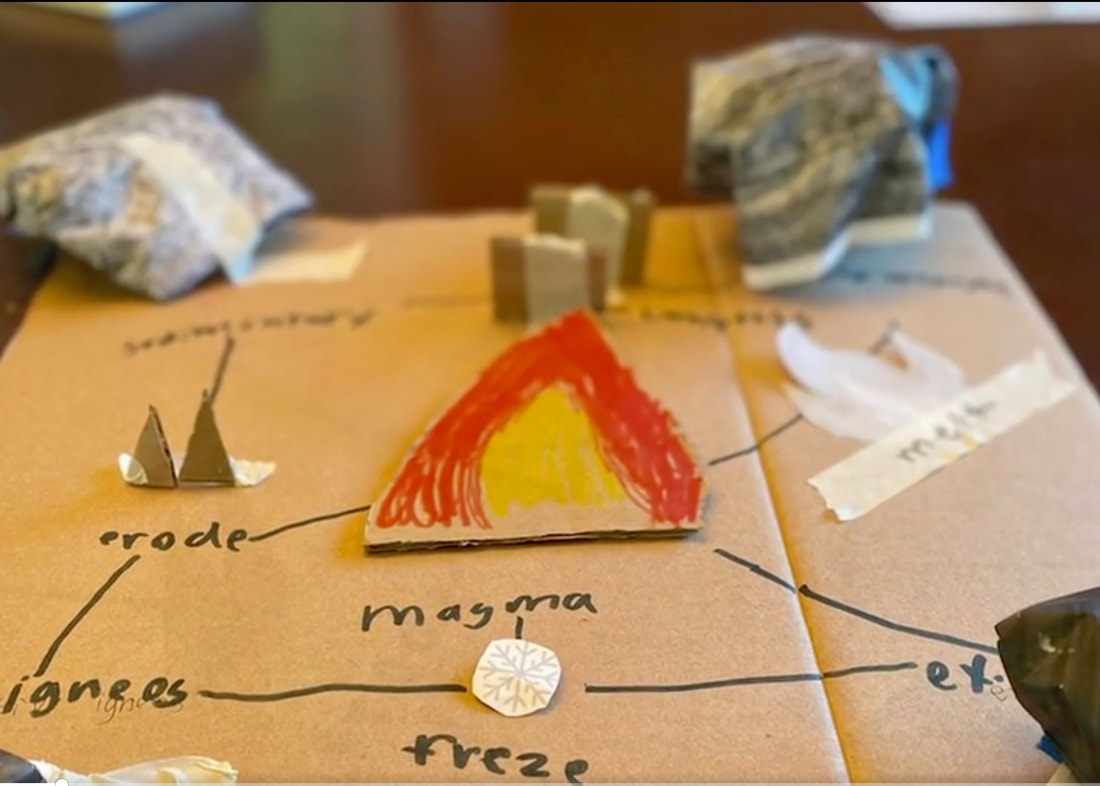

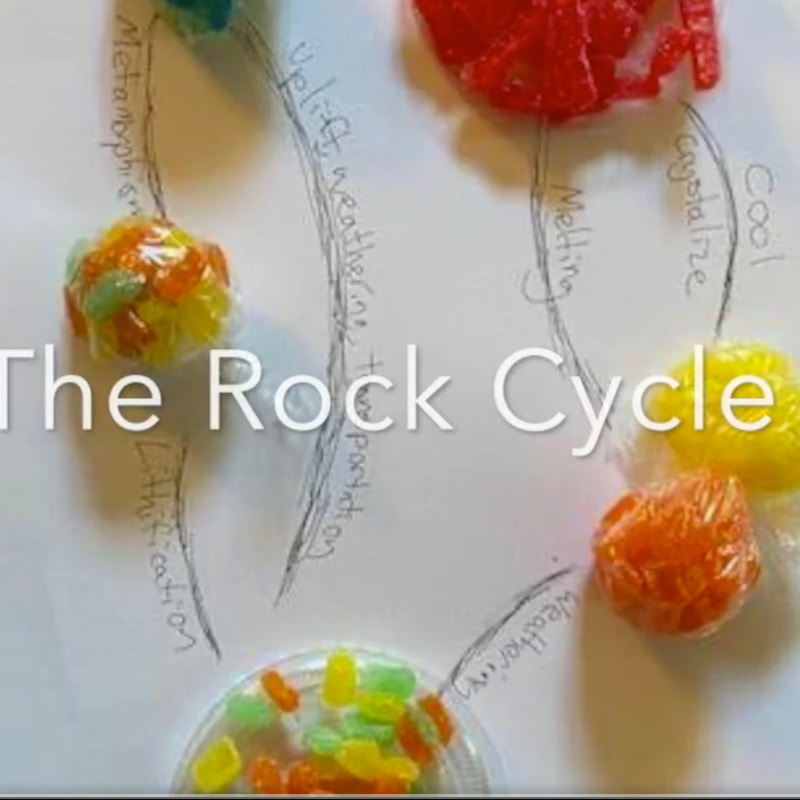

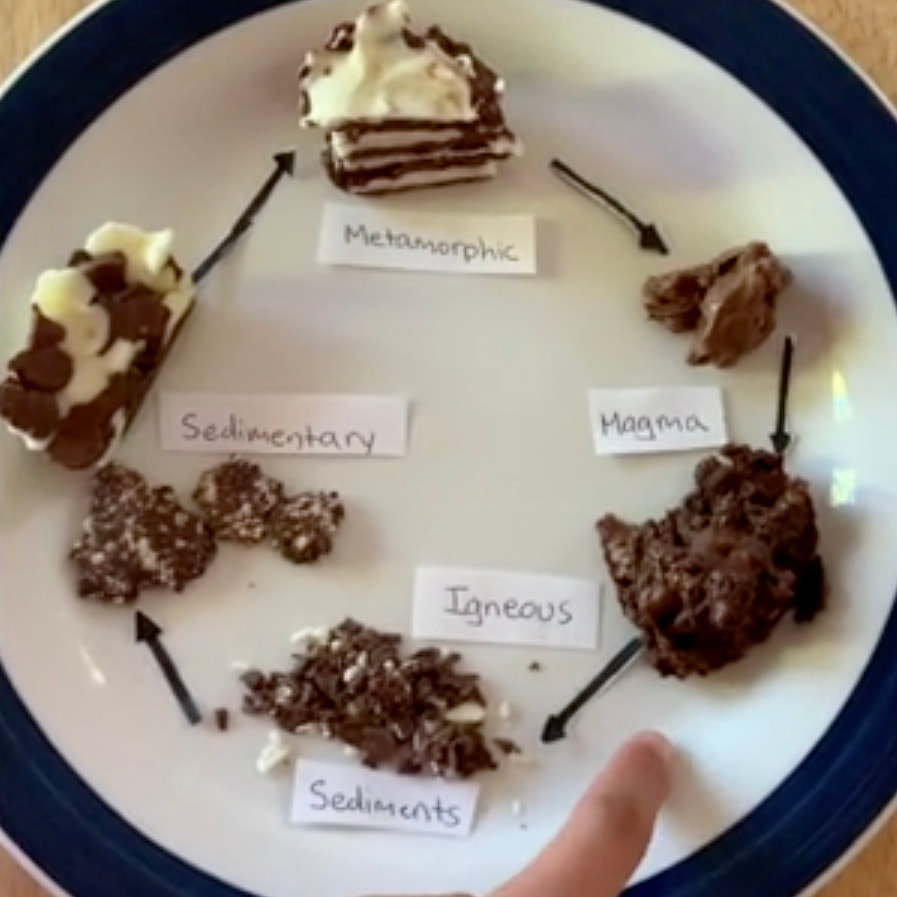

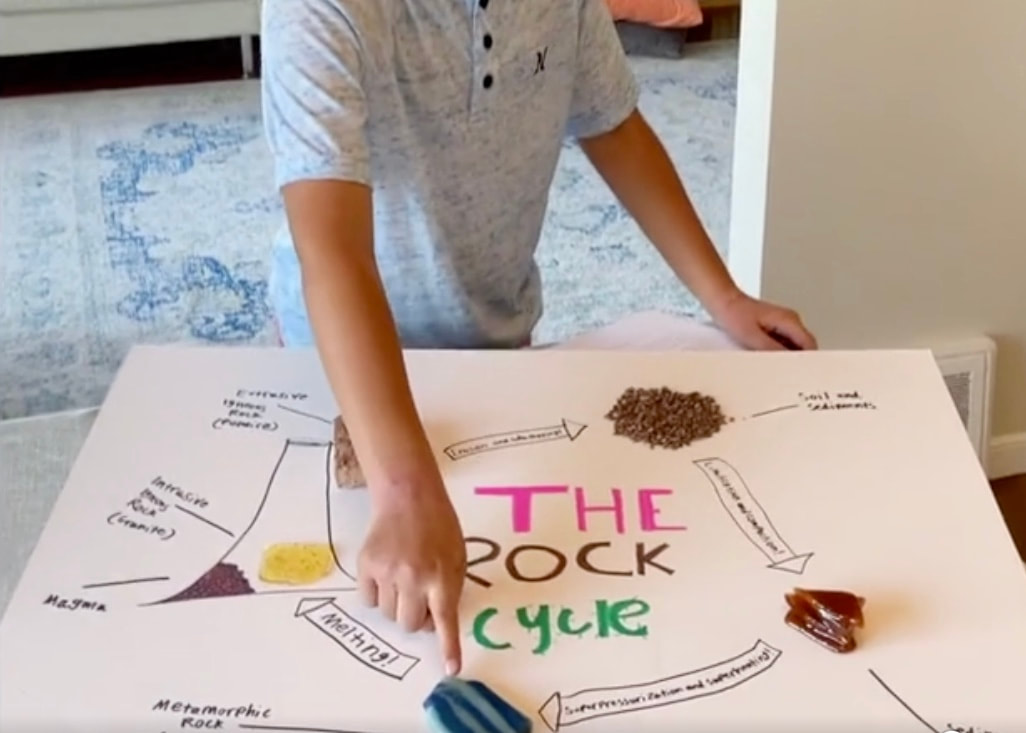

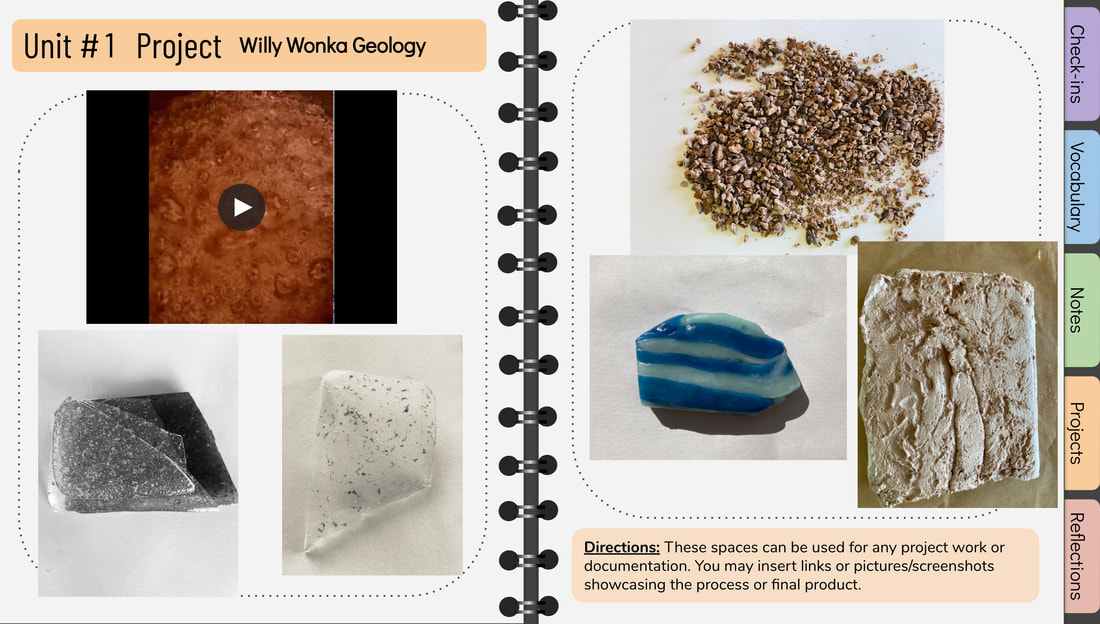

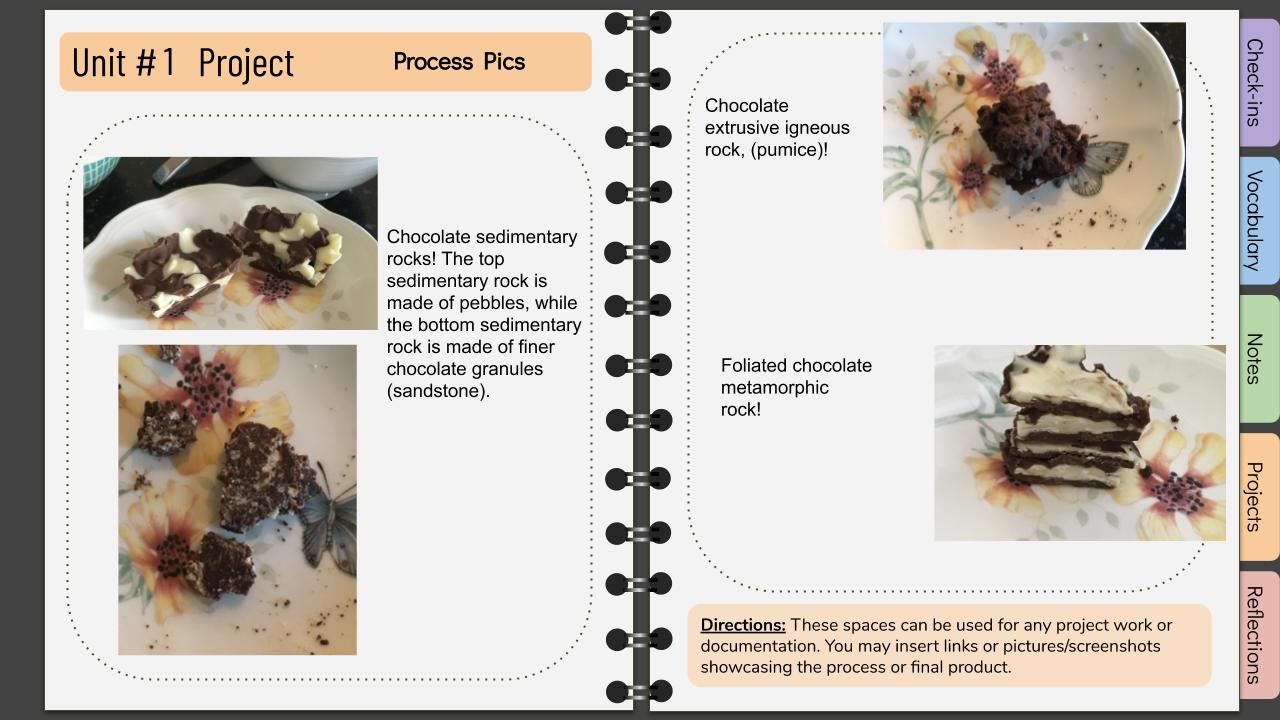

Developing models is an essential science skill. Models can help us represent abstract ideas and complex explanations. They can enable us to make predictions or determine relationships in a system. For example, we are all familiar with rocks as the most abundant features of our planet. Yet rocks are formed, de-formed, and re-formed in a cycle that's largely not able to be observed firsthand, since many of its processes occur deep within Earth or on a geologic time scale. As a culminating project in our Earth's Composition unit, since we were remote, students modeled the rock cycle with items found at home, and up-cycled or ephemeral projects were encouraged. Then, in a short video with their model, students explained the geologic processes and energy transformations involved in forming each of the three rock types (igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic). In their models, students were challenged to represent geologic processes like lithification, metamorphism, and crystallization. They totally "rocked" it, and I am amazed by the creativity! Some students used paper and cardboard to great effect... Some students used food like these sour gummies and homemade chocolates... One student even made his own candy to demonstrate each stage of the rock cycle in a project he called "Willy Wonka Geology." Check out the detail on his cocoa marshmallow "pumice" and his arrangement of the confections. All students documented their project research, brainstorming, and progress in their digital science notebook. The focus was on a process of iteration. Below are some sample science notebook pages. Watch this short compilation video and you'll see legos, clay, and other artistic mediums that the students utilized: This project was a chance for students to flex their knowledge by designing a scientific model that demonstrated Earth's dynamic recycling process in which all rock types can be derived from or form each other over geologic time. They were better able to predict outcomes of different geologic forces and discover relationships among the rock types. It was a powerful learning experience.

I am grateful to my Associate Teacher, Tim Varga, for taking the lead on developing and instructing this project work. Fellow science educators interested in incorporating the project into your curriculum, you can find our Modeling the Rock Cycle Project Doc (including instructions, timeline, and rubric) on the Shares tab above. This summer, I was delighted to pilot a new online course, Storytelling for Impact in Your Classroom: Photography, presented by National Geographic Education in partnership with Adobe. In the course, I gained a deep understanding of the power of visual storytelling and the value of photography as an instructional tool in my classroom. In the course, we were inspired by expert National Geographic photographers like Erika Larsen and Hannah Reyes Morales describing their own creative processes and tools. We explored how to compose images for maximum impact on the viewer, and we familiarized ourselves with the ethical and legal aspects of the medium. One of our final tasks was to shoot and edit a short photo series that captured a vivid sense of place at a specific location. We were allowed to include a brief intro and photo captions, but the goal was to make sure the images themselves told the story. You can view mine below. The Santa Cruz Wharf The Santa Cruz Municipal Wharf feels like an intersection of the human world and the natural world. Built in 1913, the wooden wharf stretches more than a half mile over Monterey Bay. Even in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic this summer, the wharf has continued to attract fisherman, tourists, and wildlife. Shot with iPhone. Santa Cruz, California. 8/13/20. I hope to integrate more photographic storytelling into my future science courses, so students can express themselves and illustrate concepts through a visual medium. I will convey this to students: next time you are somewhere with a camera, don't just point and shoot- aim and create. Challenge yourself to compose interesting images. Look for details others might miss. Tell an authentic story of place. With lots of practice, you might even become a National Geographic photographer.

Educators, Storytelling for Impact in Your Classroom: Photography is a free course, and it also includes complimentary access to Adobe Creative Cloud software for you and your students. The online learning is self-paced yet there are many opportunities to exchange feedback with other participants. You will gain classroom-ready resources like handouts and videos and start to develop a plan to integrate to photographic storytelling into your curriculum. Empower your students to tell their stories. If you are ready to register, please visit this webpage! Critical Creativity

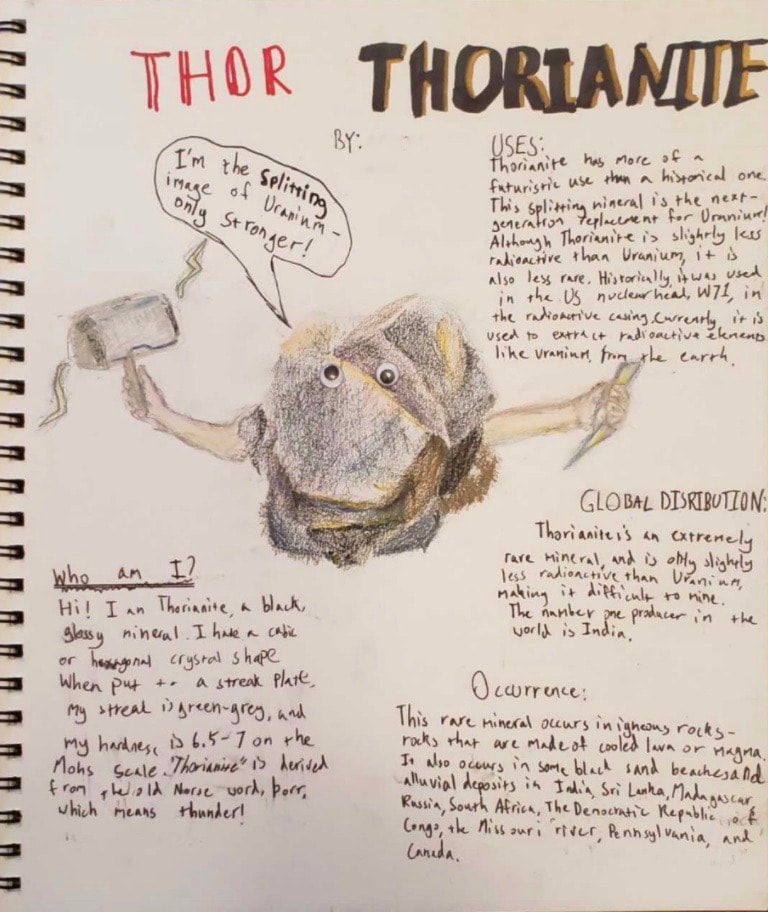

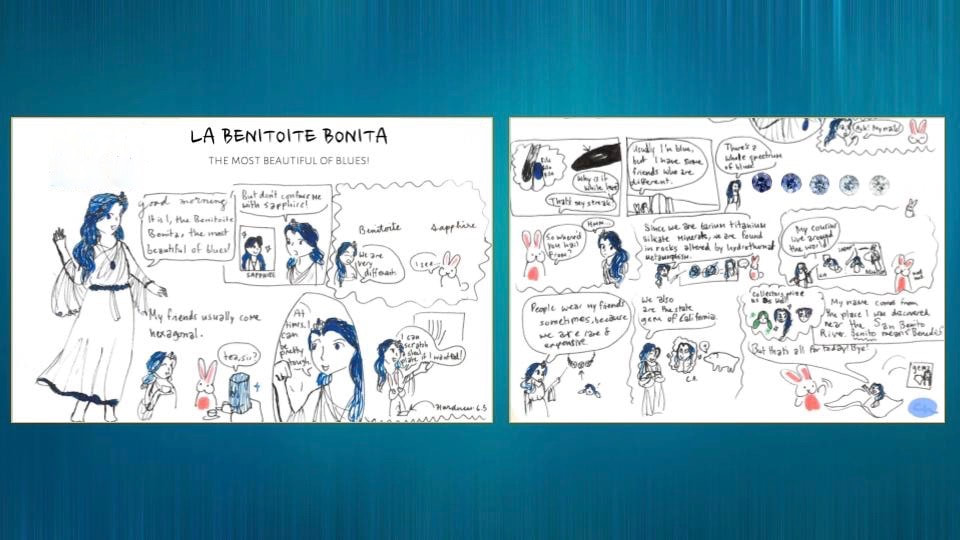

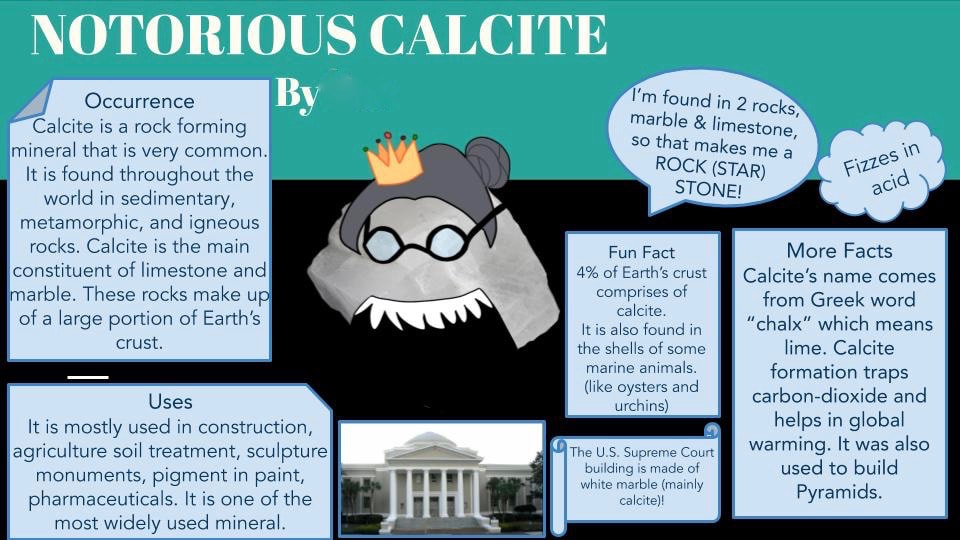

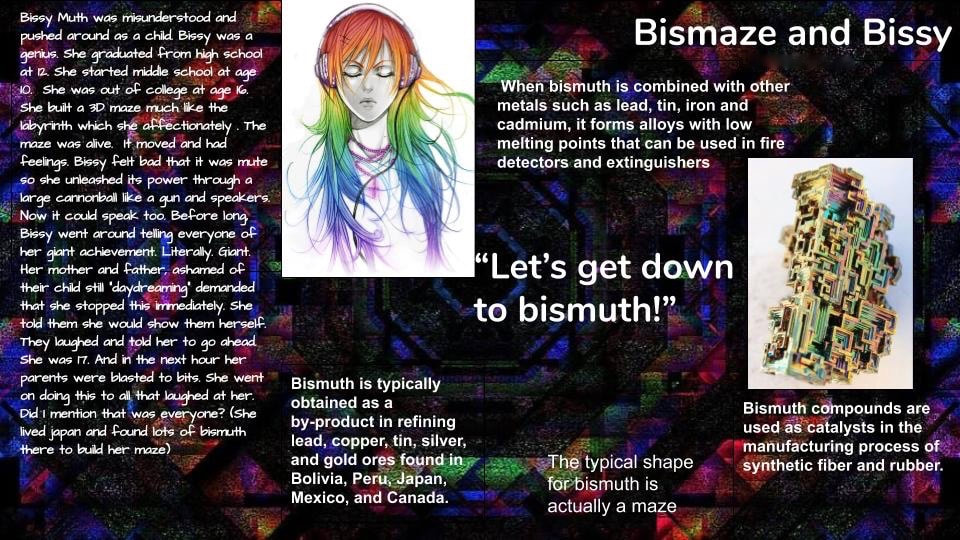

I think nurturing critical creativity is important in the science classroom and, especially in remote learning, activities like these are a fun outlet for students. Student Work SamplesSome students took the opportunity to hand draw (and photograph) their work, and some students worked with digital tools. Either way, the results were amazing. Check out some student work samples below. Quite a cast of characters, right? Fellow science educators interested in incorporating this project into your curriculum, you can find the Make-a-Mineral Doc lesson on my Shares page.

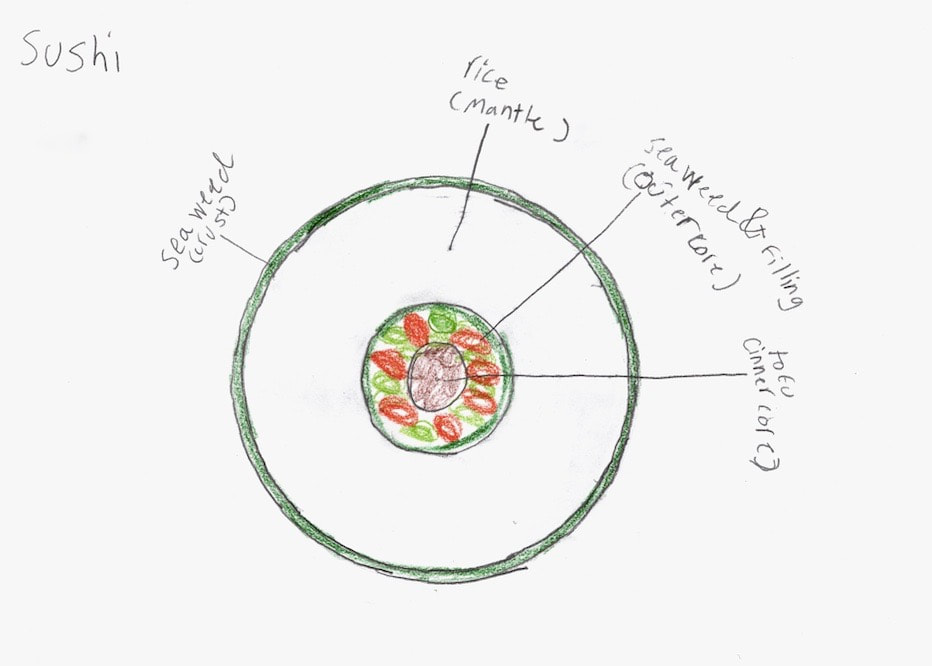

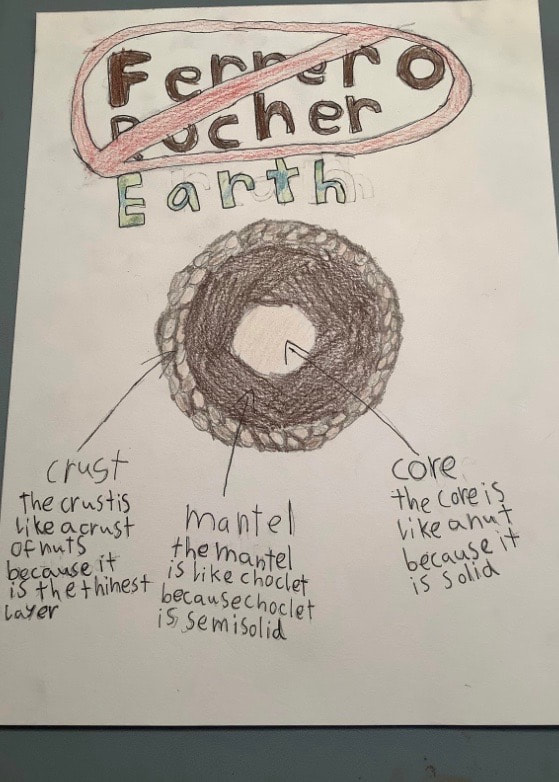

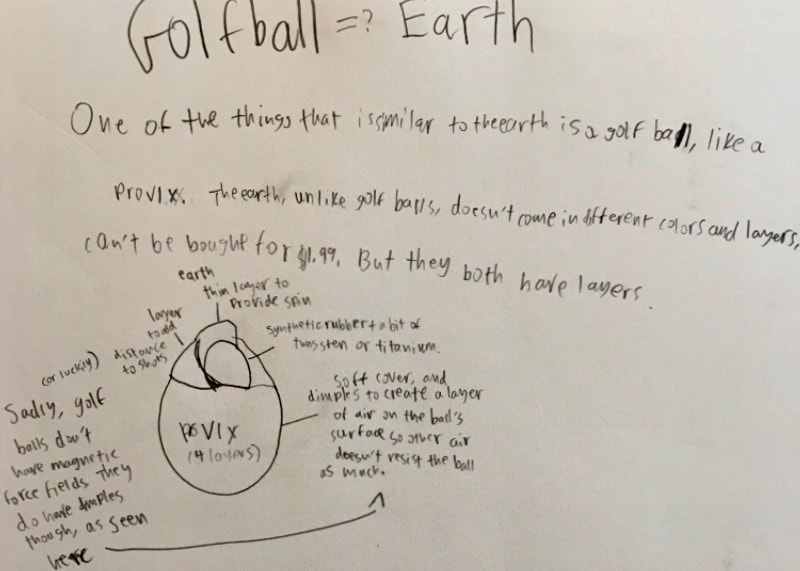

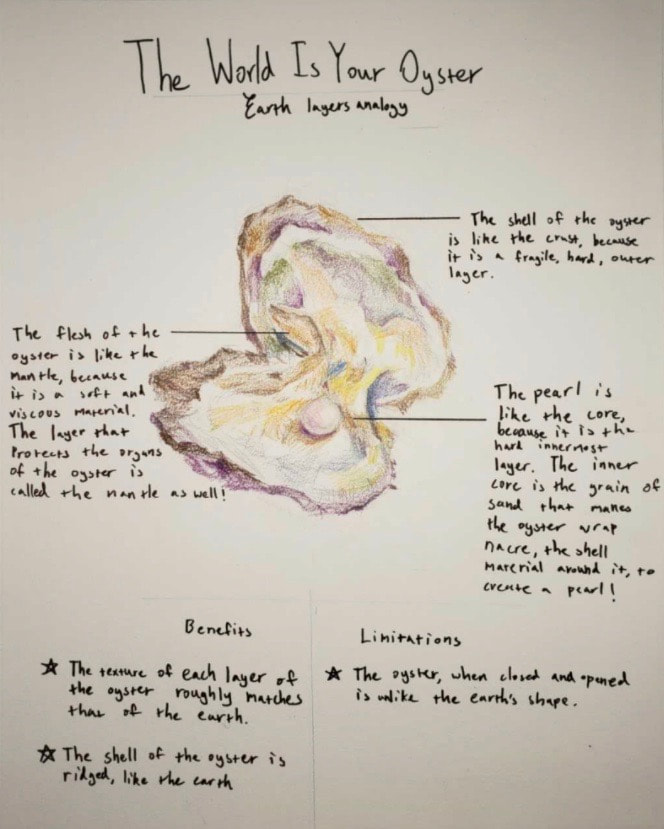

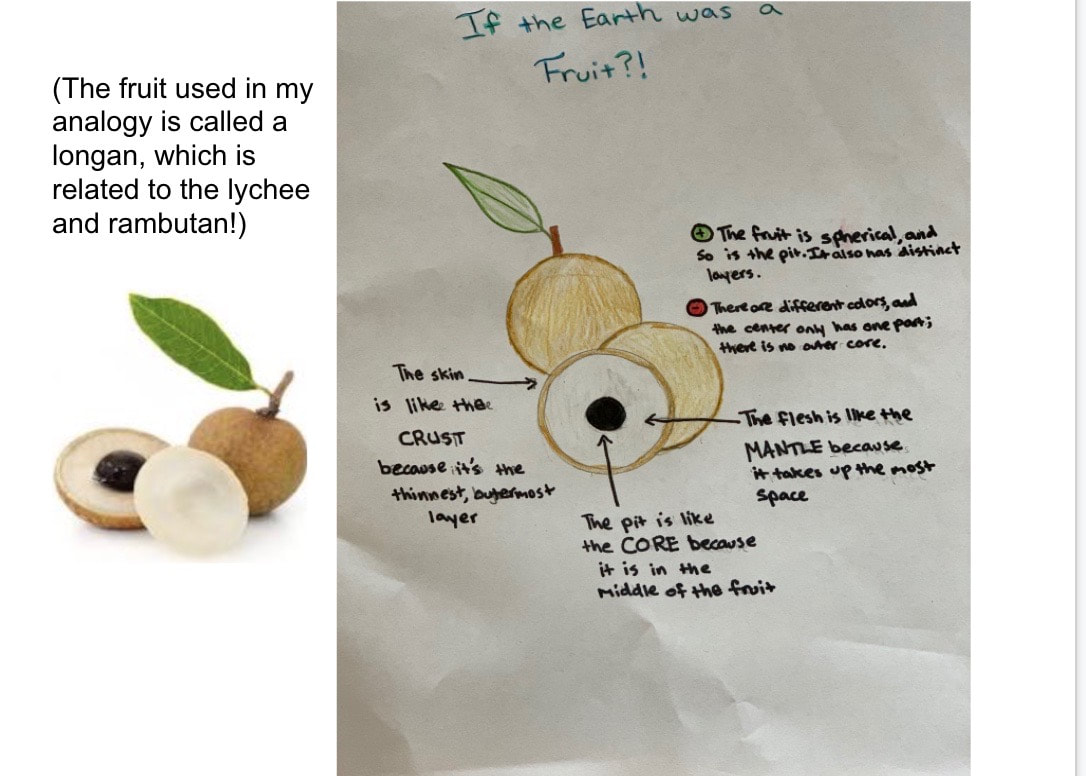

Using Analogies in Science Class

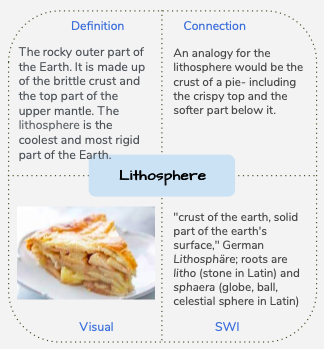

I have included analogies into a Word Study activity I've implemented this year; for selected vocabulary words, I have students complete a Word Study in their digital Science Notebook using the template below. In the "Connection" section many students opt to share an analogy to help make a connection to an unfamiliar word. Student Work SamplesIn my 5th grade Earth and Environmental Science class, I recently challenged students to come up with creative analogies comparing Earth to another layered object in an annotated drawing. Below are some samples of excellent student work. After completely their Earth analogy, students were encouraged to analyze the benefits and limitations of their model in their science notebooks. The activity was a great way for students to showcase their artistic talents while sense-making, and students appreciated the choice they had in selecting their analogy.

Fellow science teachers, how might you incorporate analogies in your teaching? What is a Naturalist?Since most of us are staying close to home this summer, we cannot widely explore, but we can deeply observe―with all of our senses― the natural beauty in our own backyards. In fact, I’ve taken the opportunity to become a better backyard naturalist, and I invite you to join me. When you hear the word naturalist, what do you think of? Charles Darwin investigating the flora and fauna of Galapagos islands back in 1835? Your birder aunt updating her detailed spreadsheet with this year’s avian sightings? The park ranger who led an interpretive hike in Yellowstone National Park on your last family vacation? Perhaps you do not even have an image to call up. Well, quite simply, a naturalist is someone who spends time in nature making observations and asking questions. Anyone can develop the mindset, and skill set, of a naturalist! Moreover, there is a robust body of research on the many benefits of spending time in nature. I will get you started by sharing a few of my recent experiences and some relevant National Geographic Education resources. Find a "Backyard" for ObservationsBeing a backyard naturalist is a great solo, family, or physically-distanced activity. I have really enjoyed the time alone, sometimes with my toddler son, exploring my backyard― about an acre of garden and oak forest in Palo Alto, California. If you don’t have a backyard, you can seek out a nearby green space or park. Somewhere close to home is great because you can quickly make some observations if time is limited. With better access, you can also vary the time of day when you can make observations, which is really useful in recognizing patterns like which wildlife are active during the day (diurnal), at night (nocturnal) or dusk and dawn (crepuscular). If you live in a city, you can use National Geographic Education's Finding Urban Nature Resource Library to help find opportunities for naturalist activities in an urban setting. Document ObservationsOne of the most important aspects of being a naturalist is documenting our observations. This could take different forms, depending on your interests. I am partial to iPhone photography, and I have included some of my insights on composition in the captions of the photographs included here. For more tips, check out Nat Geo Kids’ Take Awesome Outdoor Shots and 5 Wildlife Photography Tips. You might create a nature journal and include original sketches and annotations. Take note of the weather conditions. Think about what other quantitative and qualitative data you might include in your journal entries. Remember to include sensory details: compare the underside of the leaf to a familiar texture; explain how the air smelled after the rain; and transcribe that melodic chickadee call you heard. Beautify your nature journal with some flower or leaf pressings. Consider choosing a “sit spot” that you revisit for observations, and it may illuminate changes over time. Select one plant or square meter of land, for example, and carefully document it through the seasons. To aid your observations, you may want to acquire tools like binoculars, hand lenses, bug cases, or field guides, but they are not required to get started. So. Many. Questions.Remember, being a naturalist involves asking questions about our observations. One of the most simple ones, about an organism, is: “what is that?” Certainly, names have importance and learning to identify species is a useful skill, but it should be just the beginning of your inquiry. Naturalists wonder about about natural phenomena they witness. They ask questions concerning ecology, that is, about all the complex interactions among living things and their environment. Questions might include: why are some squirrels grey and some black?; how is that gall wasp parasitic?; what trees do woodpeckers prefer?; how does fungus pop up after a rain?; which flowers attract the most butterflies?; and why do I only hear owls at night? Sometimes the answers are revealed through systematic observation, but often the questions spark interesting research. For example, I saw tiny purple blooms growing right out of a tree trunk! It appeared to be cauliflory, when plants flower and fruit from their trunks or main branches. Yet I was only familiar with cauliflorous tropical plants like cacao, breadfruit and papaya. When I did some research, I found out that redbud trees (Cercis) like this one are fantastic local examples of cauliflory. This evolutionary trait allows trees to have their seeds dispersed or be pollinated by animals that can’t fly or climb. Looking High, Low, Close, and FarYou should visualize your backyard or other green space as a three-dimensional ecosystem like in this "Who's in My Backyard?" infographic by National Geographic Education. The infographic is helpful in that it highlights energy flow in feeding relationships. You might observe evidence of these feeding relationships firsthand; recently, I saw a jackrabbit munching on grass and I later found the scat of a coyote containing jackrabbit fur. The infographic also serves to remind us that when observing, we need to make a conscious effort to vary our perspectives to fully investigate all aspects of the space. Look high in the sky to see the hawk slowly gliding. Look low to see the tiny banana slug leaving its slime trail across the ground. Look close to discover the intricate moss growing on your back patio. Look far to spot the skittish white-tailed deer at the edge of the meadow. Keep looking. Recently, in late afternoons, I had observed swarms of moths fluttering in the canopies of my oak trees. I wondered if they were a threat to the tree health and why they were so active during the day. I could not get a great look at the moths at that height, but I decided to look closer at the tree. Clinging to the tree bark, I saw a boldly marked chrysalis that reminded me of a tiny painted bead. The creature metamorphosing inside that protective shell was a native California oak moth (Phryganidia californica). I did some research and found out that when they are in caterpillar form, a large population of oak moths can defoliate entire oak trees. However, the oaks are able to bud and produce new leaf systems and are not usually destroyed by the voracious eaters; the species have co-evolved as part of the same oak woodland ecology here in northern California. Also, most moths are nocturnal, but these oak moths produce a chemical defense against bird predators, which is why they are out during the daytime.. Uncovering HabitatSome habitats need to be uncovered, such as by turning over rocks and logs. For example, after hearing its call for weeks, I finally found a Pacific treefrog (Pseudacris regilla) this spring. Despite their name, they live on the ground; in fact, this camouflaged beauty was hiding under a rotting log. Their coloration is highly variable: bright green, tan, grey, brown or even black. Individuals can even change colors in a matter of minutes to months, depending on conditions. Recently, I lifted a log to reveal a wriggling golden treasure trove of salamanders. The slender salamanders (Batrachoseps), endemic to different regions of California, are small-limbed and mainly stay nestled in leaf litter and eat insects. Lungless, they breathe through their moist skin. Amphibians such as frogs and salamanders are important 'indicator species' of ecosystem health because they are especially sensitive to environmental changes. Remember, it is extremely important to re-cover any habitat you have uncovered. If you flip a log or rock over to inspect what's beneath it, then put it back in place to protect the creatures living there. Surveying LifeWhen you are ready to develop your species identification skills, you'll have to look closely at morphological characteristics of the organism (size, shape, structures); details like type of leaf margins, number of appendages, and position of color bands become critical. Why not use your smartphone to enhance your learning? I highly recommend the app iNaturalist, as it provides an online community of naturalists and the ability for any registered user to upload observation photos with locations. iNaturalist observations are organized in various projects, confirmed by expert naturalists, and are a form of citizen science― meaning the data collected by members of the public is used in actual scientific studies! Kids need parental permission to use the iNaturalist, but there's also a cool version for younger users called Seek. It has a gamification that can be appealing- like Pokemon but with nature. Another great citizen science all, specifically for bird identification, is eBird; use it to upload and log your own bird observations and find bird hotspots documented by the eBird user community. As a naturalist, one question you might ask yourself is “How many different species are in my backyard?” One awesome citizen science activity to help answer that question of backyard biodiversity is to conduct a biological survey of an area in a specified period of time. It's called a BioBlitz! The goal is to identify and document as many different species as possible, and you can record the data in your nature journal or with iNaturalist. Find detailed instructions for conducting one in National Geographic Education’s Backyard Bioblitz. When I conducted a backyard BioBlitz, I catalogued almost 100 species of animals and plants. Not surprisingly, the most animal diversity was among the insects; I identified red skimmer dragonflies, sweat bees, pill bugs, blister beetles, carpenter ants, yellow-faced bumblebees, painted lady butterflies, Jerusalem crickets, and so many more. Going FurtherThere are lots of different opportunities to grow as naturalists. Attracting wildlife means more wildlife observations, but it also can help conservation efforts. A fun family project might be setting up a bird feeder, a hummingbird feeder, or bat house. You could plant a native garden to welcome pollinating bees and butterflies. Finding a community of like-minded naturalists is another more social option. Local nature centers are great resources for lectures, guided hikes, and other activities once things start to open back up. Almost every US state has an official Master Naturalist program that offers courses and certification!

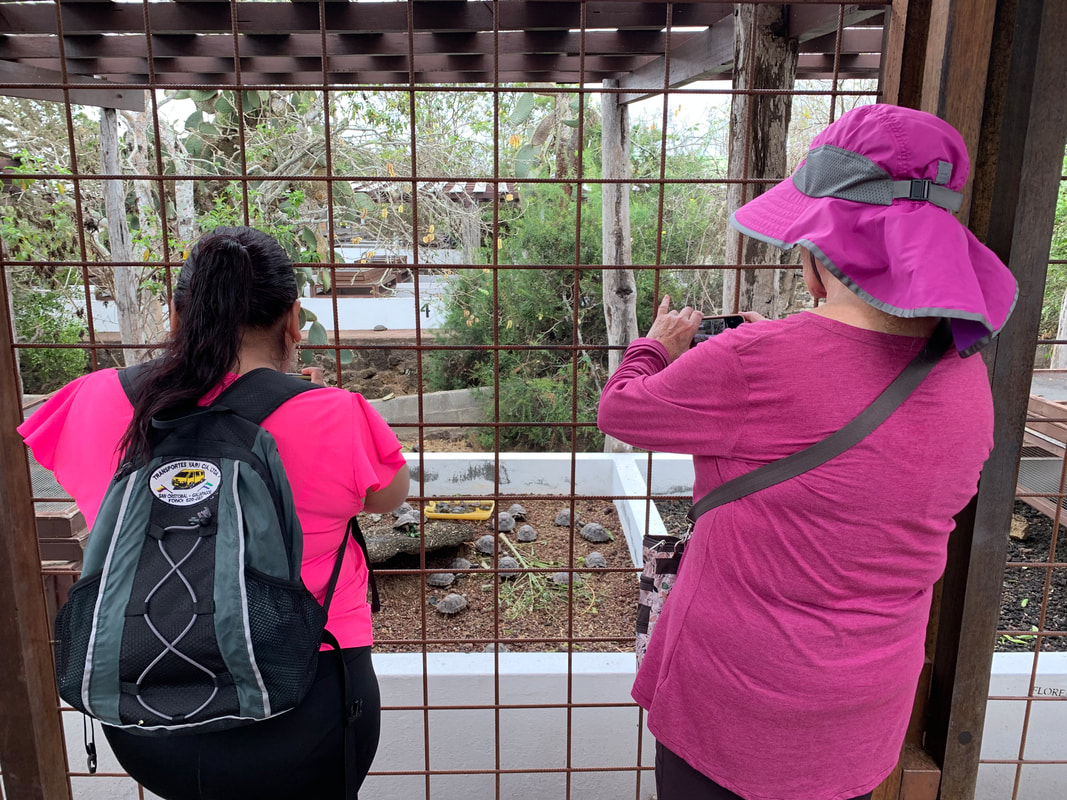

Grosvenor Teacher Fellow AlumnaTo my delight, I was offered a chance to join a National Geographic-Lindblad Expeditions Galápagos expedition as a Grosvenor Teacher Fellow Alumna. It was a tremendous professional honor and a unique opportunity to explore a place that has long fascinated me. On expedition, I gained firsthand knowledge of Galápagos wildlife, geology, and natural history as I followed in the footsteps of Charles Darwin. Now that I have returned from my voyage of discovery, I am just beginning to process all that I have learned. The Galápagos archipelago is a province of Ecuador and straddles the Equator in the eastern Pacific approximately 600 miles from the mainland. It's comprised of 13 large islands and over 40 small islands, islets and rocks. The total land area of the Galápagos islands, just over 3,000 square miles, is about half the size of Hawaii. In 1959, the Ecuadorian Government declared all uninhabited areas of the Galápagos Islands a National Park (a total of 96% of the total area). Since the 1960's the Galápagos National Park Service has managed the park with help from the Charles Darwin Foundation for the Galápagos Islands, a private non-profit scientific and conservation organization. The region's unique cultural and natural treasures made Galápagos the world’s first UNESCO World Heritage Site. What a place to explore! So, on Thanksgiving, I flew out of San Francisco on a seven hour red-eye flight to Panama City, Panama where I was thrilled to find a Dunkin' Donuts to buy a coffee. After a brief layover, I flew to Guayaquil, Ecuador to spend the night at a hotel. The next morning it was time to fly to San Cristobal Island. There, we had to clear additional customs and familiarize ourselves with Galápagos National Park rules. It was finally time to check out the port and board the National Geographic Endeavor II. Lindblad Expeditions has over 50 years experience in Galápagos: read about the ship here; and get more information about travel with Lindblad in the region here. Day 1: San Cristobal and Boarding the ShipGetting to know my fellow travelers, the naturalists, and the photo instructors was so much fun. Also, I was not the only Grosvenor Teacher Fellow Alumni on expedition. I had a fabulous partner in Kelly Meade from Long Beach, California. At David Starr Jordan High School, Kelly teaches Medical Chemistry and Epidemiology & Public Health. We bonded right away, and I was so stoked to share a cabin, and this adventure, together. I am also grateful because Kelly was able to document the experience with some sophisticated cameras, whereas I was just using an iPhone (on land) and an old GoPro (underwater). Check out Kelly's amazing photos and insights on her blog here. Though the National Geographic photographers, and most guests, had impressive camera equipment, one of the Galápagos National Park rules relating to photography is that you are not allowed to use a flash (on land or underwater). About 30,000 people live in the Galápagos. Only four of the large islands (Santa Cruz, Isabela, Floreana and San Cristobal) are inhabited. This city, Puerto Baquerizo Moreno, here on San Cristobal Island, is the capital of the Ecuadorian province of Galápagos. The island residents primarily make a living from tourism, fishing and farming. Day 2: Gardner Bay & Punta Suarez, EspanolaWe had Gardner Bay all to ourselves this morning. I quickly found out that the Galápagos National Park strictly regulates this and other sites by rotating groups through on a schedule, so we never saw another tour group at our landings or snorkel spots. You do, however, have to be in a group with a certified park guide/naturalist all times and you must stay on established trails. This particular beach is known for dazzling white sand! The sand is a result of millions of years accumulation of the organic waste of fish, breakdown of corals, and deposition of calcium carbonate; after many years of erosion, the sand develops a very fine texture. The beach is also known for its charismatic Galápagos sea lions. This endemic species of sea lion, found throughout the islands, is a separate species than its California sea lion relatives. When we got to port in San Cristobal one of the first creatures I saw were the endemic Sally Lightfoot crabs (Grapsus grapsus) scrambling on the rocks below the dock. In fact, they can be seen feeding in large groups on most beaches and in shallow water on all the islands. Here, at Gardner Bay, I finally got close to these colorful crabs! These scavengers provide ecosystem services like cleaning organic debris and eating ticks off marine iguanas. In the afternoon, we took a long hike around Punta Suarez, and were treated to some spectacular scenery and wildlife. Though the Galápagos has relatively low biodiversity, it has high rates of endemism—organisms separated from their main population and adapted to their environment, eventually changing to become a new species. There are as many as 26 endemic species among the islands including Darwin’s finches, Galápagos giant tortoises, marine iguanas, and Galápagos penguins. This is the only place on earth you can see these animals in their natural habitat. And because Galápagos animals have no instinctual fear towards humans, you closely encounter wildlife. Galápagos National Park rules require visitors stay 6 feet (2 meters) minimum distance from wildlife, and it is unbelievable to be so close to these rare and wild creatures. I think of all the famed Galápagos wildlife, I was most excited about seeing the endemic marine iguanas. The world’s only swimming lizards, these iguanas were the inspiration for Godzilla’s visage. They forage algae underwater, so they ingest large amounts of seawater. I learned two things about this: they loudly “sneeze” out the excess salt without losing water due to special glands; and they usually do it right after I stop videoing them. A large population of waved albatrosses breed and nest here on this island. The waved albatross is the largest bird in Galápagos with a wingspan of over six feet, and they are phenomenal gliders that spend most of their lives offshore. We were lucky to see pairs courtship dancing, which included bill circling, bill clacking, and head nodding. Waved albatross couples mate for life and each breeding season the female lays a single egg on bare ground which the couple take turns to incubate for up to two months until it hatches. Day 3: FloreanaWith three snorkels, most of today was spent underwater, but I did have the opportunity to go for a morning photography walk on Floreana island. Although the Galápagos Islands were visited by pirates, buccaneers and whalers from the late 1500s through the early 1800s, they remained unclaimed until 1832 when Ecuador officially took possession of the islands. In 1832 people first began to colonize Floreana Island, which eventually turned into a penal settlement. Repeated colonization attempts by penal colonies and settlers, largely unsuccessful, occurred for another century. We hiked inland to a brackish lagoon to see a flock of American flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber). Dozens of flamingoes were foraging for food in the mud. Their lovely pink coloration is determined by the amount of carotenoid pigment that they ingest in their food sources (algae, crustaceans and tiny plant material); the more carotenoid pigment a flamingo consumes, the more intense their pink color. I was so excited because I saw my first blue-footed boobies! Their odd name comes from the Spanish '‘bobo’, meaning foolish/clown, on account of their clumsy movement on land. Their most distinctive characteristic is obviously their large blue feet, which play an important role in courtship. Females are thought to select males with brighter feet, as they are an indicator of his fitness and the quality of his genetic material. Thus, males make quite a performance of showing off their feet! Galápagos National Park rules prohibit collecting anything, but it was still fun to go beach combing and find shells, sea turtle bones, and various sea urchin tests. Day 4: Puerto Ayora/Darwin Research Center/Highlands, Santa CruzToday we were off the ship the entire day on the island of Santa Cruz. We were shuttled by Zodiac to the bustling port city of Puerto Ayora. Over half of all “Galapagueños” live in this city, and it's the center of tourism and conservation. Puerto Ayora has the best developed infrastructure in the archipelago. The small downtown area has some hotels, restaurants, tour companies, convenience stores and gift shops. The main street, Avenida Charles Darwin, runs between the main dock and the Charles Darwin Research Station. Along this avenue, I was absolutely captivated by an outdoor fish market. Men cleaned the day's catch as frigate birds swooped in and pelicans and sea lions circled their feet. Locals came up to make purchases while tourists and policemen watched the scene. My pictures of the fish stall in Puerto Ayora, Galápagos illustrate connections between the human and natural world that I try to address in my science courses. To engage student curiosity, I’m going to use it as the focus of a See-Think-Wonder exercise in class. Educator-Explorer friends, consider using this powerful thinking routine with some rich images from your own travels.  We toured the Charles Darwin Research Station and Museum. I had been really looking forward to this, as the foundation's Executive Director Dr. Arturo Izurieta Valery has been a featured guest speaker onboard the ship and he and his wife were frequently on excursions with me. The mission of the Charles Darwin Foundation is "to provide knowledge and assistance through scientific research and complementary action to ensure the conservation of the environment and biodiversity in the Galapagos Archipelago." Read more about the Charles Darwin Research Station on their website. I loved seeing all the different species of tortoises in their captive breeding program. They had tortoises at all stages of life from baby to elder. I felt a bit melancholy seeing Lonesome George, though. A male Pinta Island tortoise and the last known individual of the species, George was cared for at the research station for forty years (by the same primary caretaker) until his death in 2012. After his death, Lonesome George was shipped to New York and underwent a taxidermy process by experts at the American Museum of Natural History before being returned to Ecuador. Now a preserved specimen on display, Lonesome George is still an important symbol for conservation efforts in the Galápagos islands and the world.

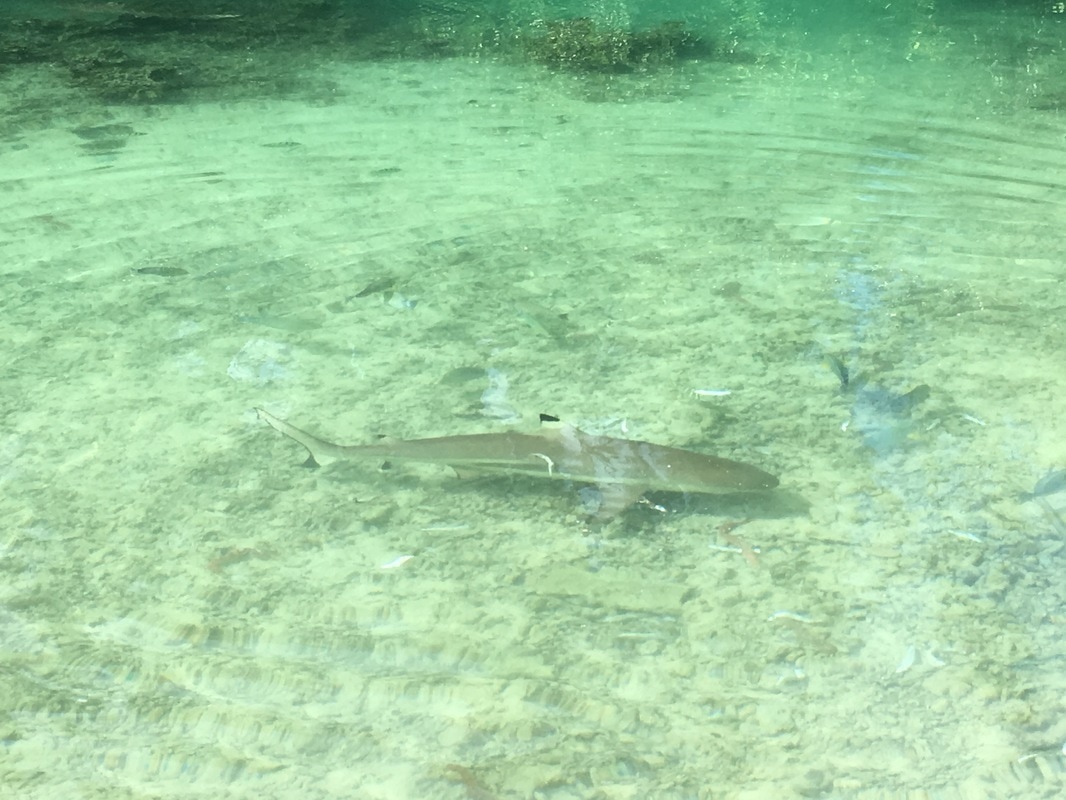

Darwin arrived in the Galápagos Islands on September 15, 1835. He spent just five weeks in the archipelago, but he later wrote that the wildlife of the Galápagos islands were central to all his scientific thinking. While in the islands, Darwin, who suffered from seasickness, spent most of his time taking notes on land features and collecting specimens of unknown species. Upon his return to England, as he reviewed his notes and specimens, he began to develop his “Theory of Natural Selection." Twenty years after he first postulated the theory, due to both desiring more data and ducking controversy, he would finally publish On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. His radical idea, the driving force behind evolution, is the central unifying theory of biology. While adventuring with the support of National Geographic Education and Lindblad Expeditions as a Grosvenor Teacher Fellow Alumna, I had a chance to learn about Lindblad’s education initiatives in Galápagos. First, that afternoon in Santa Cruz, I visited Tomás de Berlanga, a bilingual PreK-12 school that has a project-based approach to learning and a campus fully immersed in nature. I loved the playground: no foam mats or AstroTurf here. The school receives funding from Lindblad Expeditions, including support for its lending library— the first of its kind in Galapagos! I was pleased to bring a few new books I had bought at the Nueva School Book Fair as donations. Second, despite a language barrier, I got to know three teachers from Galapagos that were invited guests on the voyage. In fact, Lindblad Expeditions has sent hundreds of Ecuadorian teachers on expedition in the archipelago over the years. I am proud of this commitment to local education. We had lunch and spent the rest of the afternoon up in the lush, rainy highlands. Observing Galápagos giant tortoises (Chelonoidis nigra) in the wild is a thrill, but you have to be careful where you step! I saw the herbivores lumbering through field and forest. The “giant” tortoise title is well-deserved— they can get up to 500 pounds! They are the longest-lived of all vertebrates, living more than 100 years. Centuries of being hunted for food left populations critically endangered but the species has been protected by the Ecuadorian government since 1970 and repopulation efforts by the Charles Darwin Research Station have been very successful. Fun fact: though they are largely solitary roamers, a group of tortoises is called a creep. Love that collective noun! Day 5: Cerro Dragon, Northern Santa CruzToday, was all about trying to find the elusive Galápagos land iguanas (Conolophus subcristatus) on a long hike in the northern part of Santa Cruz island known as Cerro Dragon or "Dragon Hill." The sun was scorching and the dry landscape was covered in sparse stands of cactus and palo santo trees, the latter giving the air a slightly sweet licorice smell. Remember, Santa Cruz is the island with the largest human population in Galápagos, so unfortunately, many domestic animals have gone feral; wild goats, cats, and dogs had been decimating the iguana populations for decades. However, recent efforts of the Charles Darwin Foundation and the Galápagos Park Service to re-populate the iguanas and remove feral animals have been effective, and the iguana population has been on a steady increase. We were determined to find some of these dragons! We saw four individual Galápagos land iguanas but they were pretty far off the trail, and it was hard to get a good picture with my iPhone. Luckily, Kelly shared some of her pictures like the one below. The Galápagos land iguana is one of three species of land iguana endemic to the archipelago (one of the others being a pink Galápagos land iguana). Their skin is generally yellow with white and brown blotches. They have short heads and powerful hind legs with sharp claws. Despite the threatening appearance, they are primarily herbivores who feed on fruit and prickly pear leaves. These large reptiles have a mutualistic relationship with finches, who eat ticks from their scaly backs. Did you know Galápagos native flowers are only either white or yellow? There are few insects in the archipelago, so plants don't have to work as hard to compete for their attention. Because, you know, evolution. Day 6: BartolomeToday was all about geologic wonders and sweeping vistas while hiking on Bartolome islet. The Galápagos Islands are one of the most active oceanic volcanic regions on Earth, and I was definitely reminded of this while on the near-barren, almost Martian landscape. The islands are on the Nazca tectonic plate, above a hot spot that produces a plume of hot magma, adjacent to a mid-oceanic ridge, atop what's known as the Galápagos Spreading Center. When magma finds a weak spot in the plate above, it rushes to the surface, creating a volcano. The volcano is eventually carried away from the hot spot by plate movement and a newer volcano is created in its place. Thus, over time, the hot spot made the Galápagos archipelago. The Nazca plate is moving in a south-easterly direction, so where are the oldest island in the island chain located? Very few plan species can survive this drought-prone habitat, but there are some low-growing plants, lichens, and native cactus. I loved seeing the sooty lava flows and rust-colored "spatter cones.". The islet's golden sand here originates from the ochre-colored tuff cones that are comprised of silt loam and have a clay-like texture. On account of the strong ocean breezes here, erosion occurs daily. To help control erosion, the "trail" is a wooden boardwalk and a series of staircases (376 steps in total!) that lead to the summit of the islet. The view from the top is stunning, with a near 360-degree view of the surrounding islands and the iconic Pinnacle Rock formation. Pinnacle Rock, an old volcanic cone, was formed when magma was expelled from an underwater volcano; the sea cooled the hot lava, which then exploded, and many thin layers of basalt formed the rock. Some say Pinnacle Rock looks like a shark tooth, some say a sail. The afternoon was spent snorkeling down at the base of Pinnacle Rock, and I felt so fortunate to see some endemic Galápagos penguins (Spheniscus mendiculus) both on the shore and under the water! Sighting them is very rare. They’re the only penguin found north of the Equator and cool ocean currents allow them to live in the tropical latitudes of the archipelago. The weather here is periodically influenced by the El Niño events, which occur about every 3 to 7 years and are characterized by warm sea surface temperatures, a rise in sea level, greater wave action, and a depletion of nutrients in the water. Past El Niño events have resulted in an approx. 75% population mortality due to prey species decline and reduced breeding success. There are currently less than 1,500 individual Galápagos penguins left. Climate scientists predict that future El Niño events will become more frequent and severe due to global climate change; has the fate of this endangered species been sealed? Day 7: GenovesaToday, I went on a few different hikes in the birder's paradise known as Genovesa island. Because it is somewhat remote, many land species never made their way to this island, allowing birds to dominate. Indeed, thousands of birds nest here. As we approached the island, storm petrels, boobies, and great frigates filled the air. Huge birds walked the shoreline and roosted in the red mangroves lining the coastal trail. In addition, sea lions lumbered on the sand and marine iguanas sunned themselves on rocky tidal pools. Let's talk about booby birds! On expedition, I saw all three Galápagos species. The smallest, the red-footed booby (Sula sula) that, despite its webbed feet, perches on branches. They are fast swimmers and can dive up to 130 feet deep. The Nazca booby (Sula granti), pictured here with a chick, often lays two eggs days apart and one of the hatchlings will kick the weaker one out of the nest. And of course the iconic blue-footed booby (Sula nebouxii)! They look clumsy on land, but they reach speeds of 60mph while dive-bombing for fish. Fun fact: a group of boobies is referred to as a congress, a hatch, or a trap. I for one prefer a "congress of boobies." We saw a Galápagos short-eared owl (Asio flammeus galapagoensis) on a rocky ledge and then later walking across the trail! It is a sub-species of the short-eared owl, a bird which is found on all continents but Antarctica. Most owls hunt at night, yet this owl has adapted to hunt in the day to avoid competition with the Galápagos hawk. Underwater GalapagosThe terrestrial wildlife and the habitats of Galápagos were spectacular, but the underwater world was equally impressive! Although the islands are in the tropics, the Humboldt Current brings cold, nutrient-rich waters to the archipelago, making Galápagos a rich oceanic oasis. In fact, all the iconic species you encounter on land, such as the marine iguanas, sea lions and seabirds, depend on the productivity of the seawater surrounding the islands. Exploring by snorkel at different sites, I was surrounded by thousands of beautiful tropical fish, colorful invertebrates, playful sea lions and graceful green sea turtles. I didn't always capture everything with the GoPro (especially after it died halfway through the voyage), but it will be forever in my memory. Though they were not very active on land, all the sea lions were very acrobatic underwater! Swimming with them was a blast! Anyone else swim towards sharks when snorkeling? I was stoked to get a quick look at this beautiful white tipped reef shark (Triaenodon obesus). Galápagos sharks and hammerhead sharks are also not uncommon, but unfortunately I did not see any. Oh the absolutely magical experience of snorkeling in tropical water and having penguins unexpectedly swim by! This was my favorite moment of the expedition. Adios and GraciasIn 2014, I had the opportunity to voyage through Arctic Svalbard as a National-Geographic-Lindblad Expeditions Grosvenor Teacher Fellow (GTF). Exploring the Galápagos as a GTF Alumna is like having a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Twice. Educator-Explorer friends, please read more about this extraordinary professional development program here.

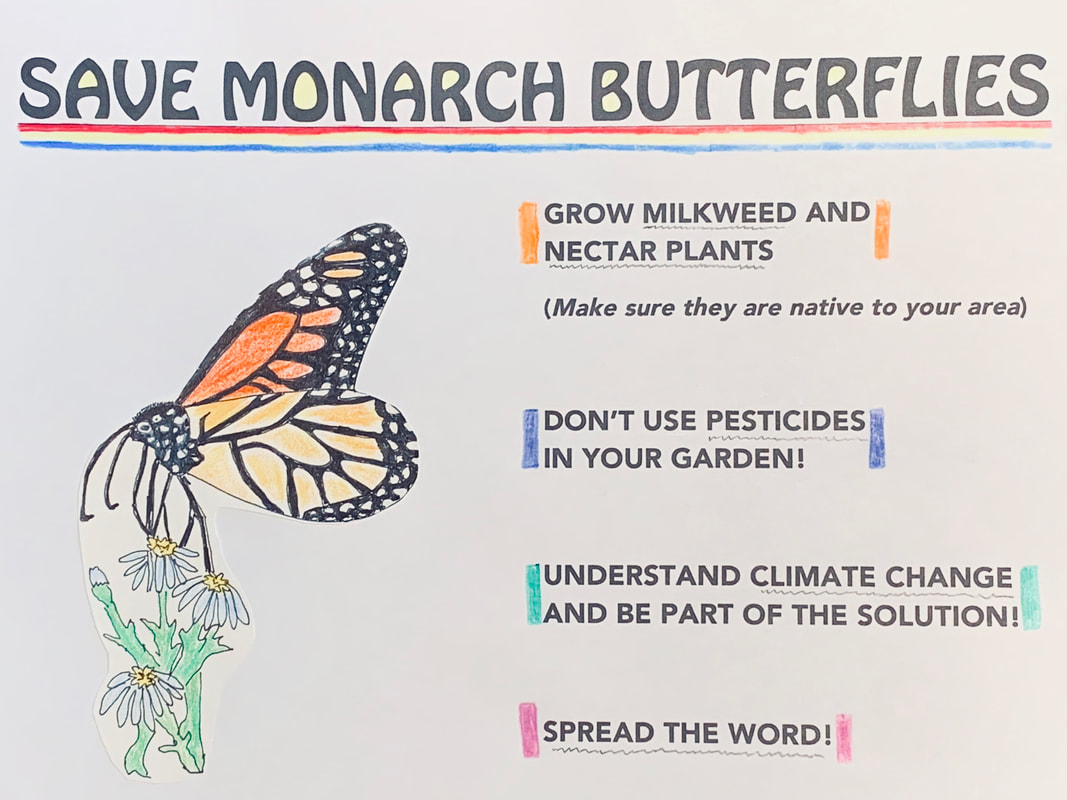

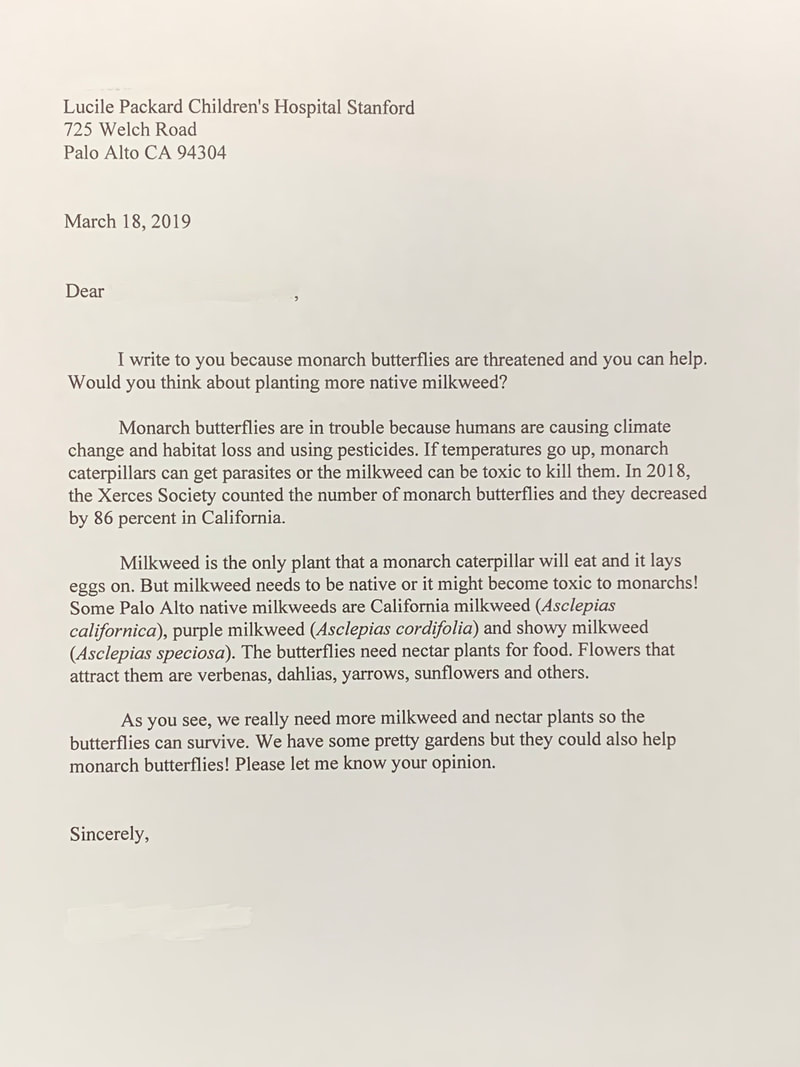

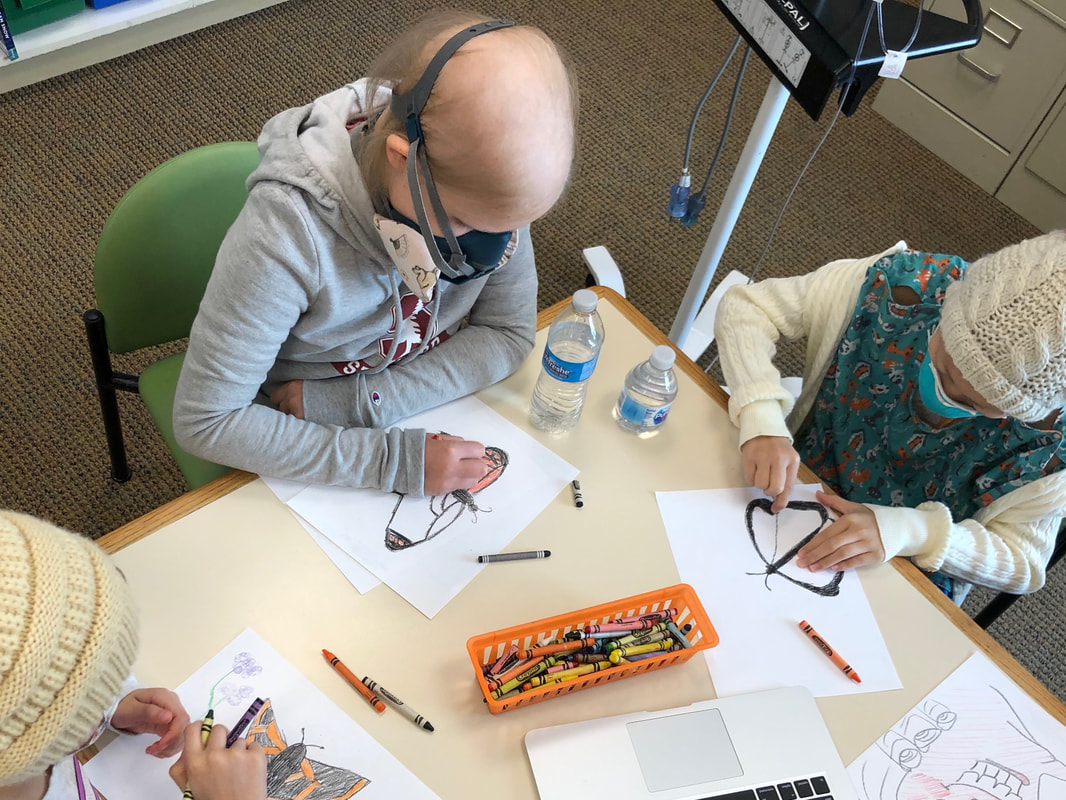

Overall, as I think back to my time on expedition in Galápagos, I have a strong sense of urgency about protecting this incomparable region of our planet and all its natural and cultural treasures. I am now more aware of how the fragile ecosystems of the Galápagos islands are impacted by tourism and under threat from invasive species and climate change. Sailing as a GTF Alumna was a privilege but also a responsibility; I consider myself an ambassador for the Galápagos islands and will do all I can to educate others. In a future blog post, I will be sharing how I have incorporated my expeditionary learning into my classroom and beyond. I miss our ship the National Geographic Endeavor II and all the incredible crew, naturalists, and fellow travelers. For now, I want to express deep gratitude to leaders at National Geographic Education and Lindblad Expeditions for honoring me with this experience. Also, thank you to all those who made my expedition possible, including my principal, colleagues, and students at the Nueva School. This voyage of discovery is dedicated to them! National Geographic Educator CertificationWhile I've been very fortunate in taking an extended maternity leave with my son, I really miss the classroom! One source of enrichment for me this year has been volunteering at the Lucile Packard Children's Hospital School at Stanford. I love the engagement with students, whether helping them with coursework or playing educational games. Volunteer teaching there has also allowed me to complete a National Geographic Educator Certification course. It's been a powerful learning experience that I'm excited to share with you all. National Geographic Educator Certification is a free professional development course open to any preK-12 educator committed to helping students investigate the world and positively impact it. In the three-month course, I refined my skills incorporating natural-human world interactions and multiple scales & perspectives into my instructional design. I've also been introduced to the National Geographic Learning Framework that's built around a set of Attitudes, Skills, and Knowledge embodied by their Explorers. I especially appreciated the sense of community in the online network of participants. The course culminated in using Nat Geo resources to teach two lessons and then producing a capstone video that highlights one of them. In my capstone lesson, students learned how monarch butterfly populations are being impacted by human activities. Lesson Overview and VideoFirst, students read and discussed a National Geographic article about monarch butterfly population decline due to global climate change and habitat loss. Next, students summarized the article in narrative structure by constructing an And-But-Therefore (ABT) statement. Then, students learned more about effective persuasive letter writing with a resource from National Geographic Kids. Finally, after researching native host and nectar plants, students wrote letters to Stanford about growing more of these plants on campus to aid in monarch butterfly conservation. I'm very proud of what students accomplished in this one lesson. At first, I was worried because the hospital school environment prohibits some of the practices previously central to my science teaching like outdoor field work and and long term investigations. Yet I discovered that I can utilize the National Geographic Learning Framework in any setting. In fact, constraints often just make educators like me more creative. Lesson Plan and Other ResourcesHere's the Motivate for Monarchs! lesson plan I developed, which is aligned to the Next Generation Science Standards and the Common Core State Standards in ELA/Literacy. In it, I've also included many ideas for extensions from planting a butterfly garden to participating in citizen science projects. In addition to the lesson plan, you'll find my Persuasive Letter Rubric and the Background Research Recording Sheet. You have all the resources you need to implement this lesson as soon as tomorrow! All documents combined in one PDF can be easily downloaded by clicking here. Please contact me if you'd prefer editable documents, for I'm happy to have teachers customize or re-mix this lesson as needed. Keep in mind, the framework of this lesson can be used for any conservation issue students are passionate about. Summarizing scientific text with ABT statements and writing persuasive letters are highly transferable skills that help improve science literacy. The lesson could also be a wonderful interdisciplinary project for science and language arts classes. Get #NatGeoCertifiedThrough their Educator Certification program, National Geographic supports the growth of teachers who are inspiring the next generation of "explorers, conservationists, and changemakers." That's a mission you'll surely want to join. Also, teachers from the Certified Educator Community are eligible to apply for the National Geographic-Lindblad Expeditions Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship Program, an incredible professional development experience that includes an expedition in places like the Galapagos, Iceland, or Antarctica.

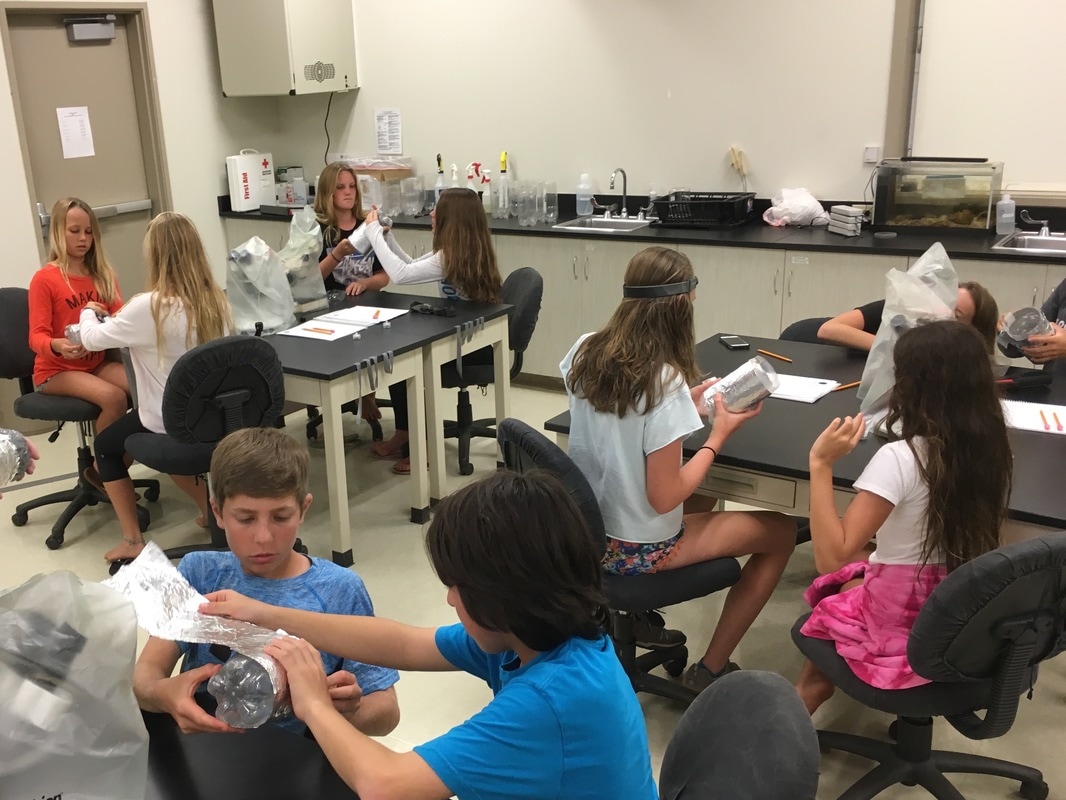

You might remember I was honored with a Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship in 2014 and voyaged in 'The Land of the Ice Bears'— Arctic Svalbard. This was before the Educator Certification process was developed. It's been amazing to continue my learning journey with National Geographic, and now I am (hopefully) soon-to-be Nat Geo Certified. If you're interested in registering for an upcoming cohort or want more information, click here and start exploring! Departing for Coconut Island What is it like to spend 24 hours on a private island in beautiful Kāneʻohe Bay conducting scientific field work? A group of my 7th grade students from Le Jardin Academy just found out. I had the privilege of bringing 15 students, all stoked on marine science, to the Hawai'i Institute of Oceanography (HIMB) on Moku o Loʻe (Coconut Island) for an overnight trip. Scientists from all over the world come to HIMB to access the marine environments and utilize their world-class laboratory facilities. Saturday afternoon, our group took the quick shuttle boat rides over to the island to begin our own marine science adventure. Setting Up Camp Our guide Leon from the HIMB Community Education Program welcomed us to the island and, after a safety briefing, everyone got to work pitching tents and organizing our gear. We had a long day (and night) of science ahead of us, so we had to get camp set up. We were all happy to be on the island and were impressed with the view from our campsite! Touring the Hawai'i Institute of Marine Biology Next, Leon gave our group a comprehensive tour of Coconut Island and the public areas of HIMB, sharing information not only about their current oceanographic research projects but also about the fascinating history of the 28-acre island. Students were impressed to learn how the island has evolved over time. Some of the island's uses include: an outpost for native Hawaiian fishermen; a lavish private estate complete with exotic zoo; and a world-renowned research institution operated by the University of Hawai'i. You can read a detailed history of the island here.

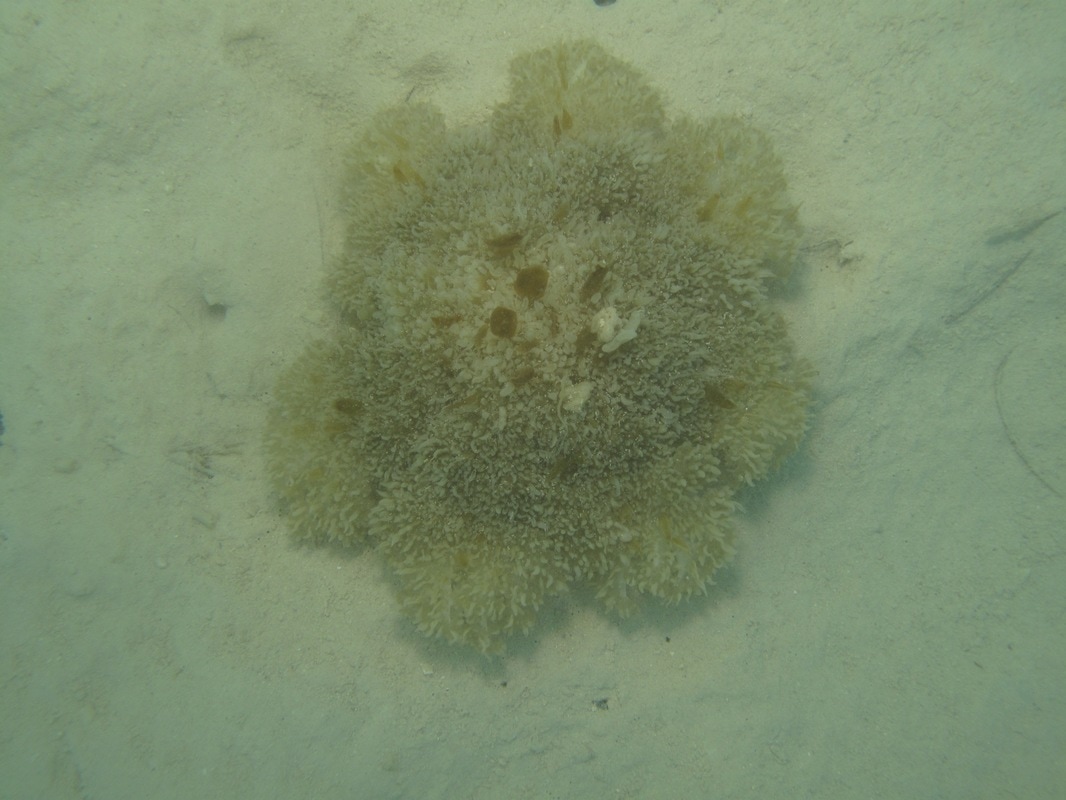

Not surprisingly, some of the most popular destinations on the tour were the shark labs. In two different pens, we observed blacktip reef sharks and hammerhead sharks getting fed. We also visited a large enclosure and watched scalloped hammerhead sharks and sandbar sharks cruise below. Students learned about HIMB's current shark research projects involving shark-human interactions, spawning migrations and foraging strategies of top predators, and digestive physiology and navigational abilities of sharks. Students gained a new appreciation for our local sharks; in fact, Kāneʻohe Bay is an important breeding ground for the hammerheads. You can read an overview of the research conducted at HIMB's labs here. Setting Up Our Coral Larval Experiment Next, we joined graduate student Raphael Ritson-Williams of HIMB's Gates Lab. In his graduate work, he is studying how corals respond to local and global stressors, including climate change, and he told students about the recent coral bleaching events in Kāneʻohe Bay. Raphael also explained his work in larval ecology, and he gave us the unique opportunity to participate in an actual coral larval experiment that was set-up in the lab's outdoor seawater system.

Getting in the Water... Now it was time to get in the water and explore the bay! Raphael and I explained how scientists quantify habitat and biodiversity in different environments, including coral reefs, by conducting a transect survey. Students grabbed their transect lines and quadrats and used these real scientific tools to survey an area of coral reef next to the island.

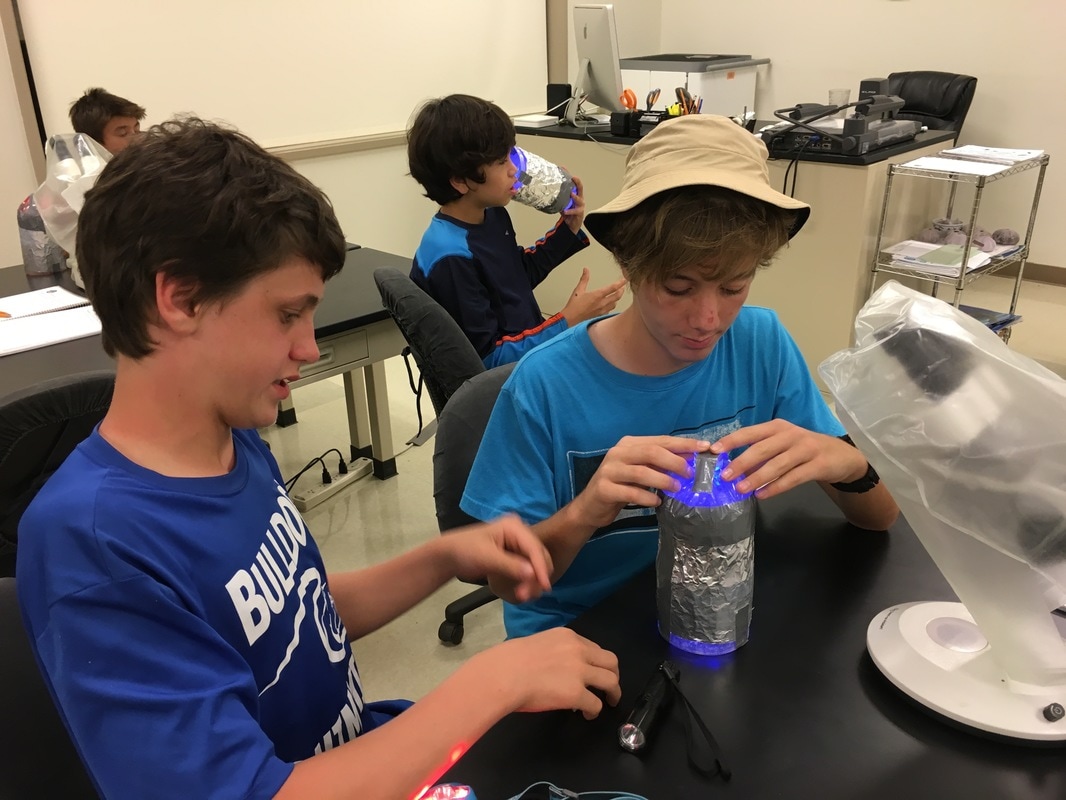

Conducting a Night Plankton Lab Once we got cleaned up, the sun began to set and it was time for dinner. We had to fuel up before our night plankton lab. We were not done science-ing yet!

We found that blue LED lights attracted more plankton than the red...Do you know why?

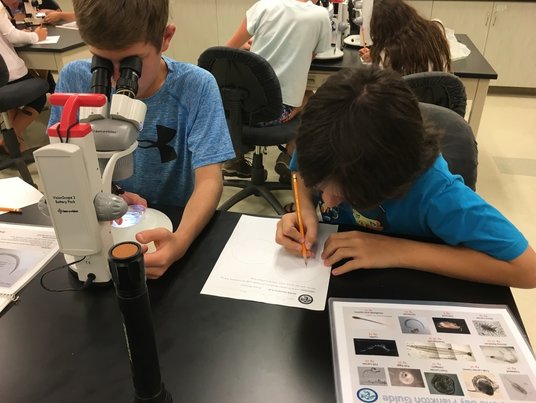

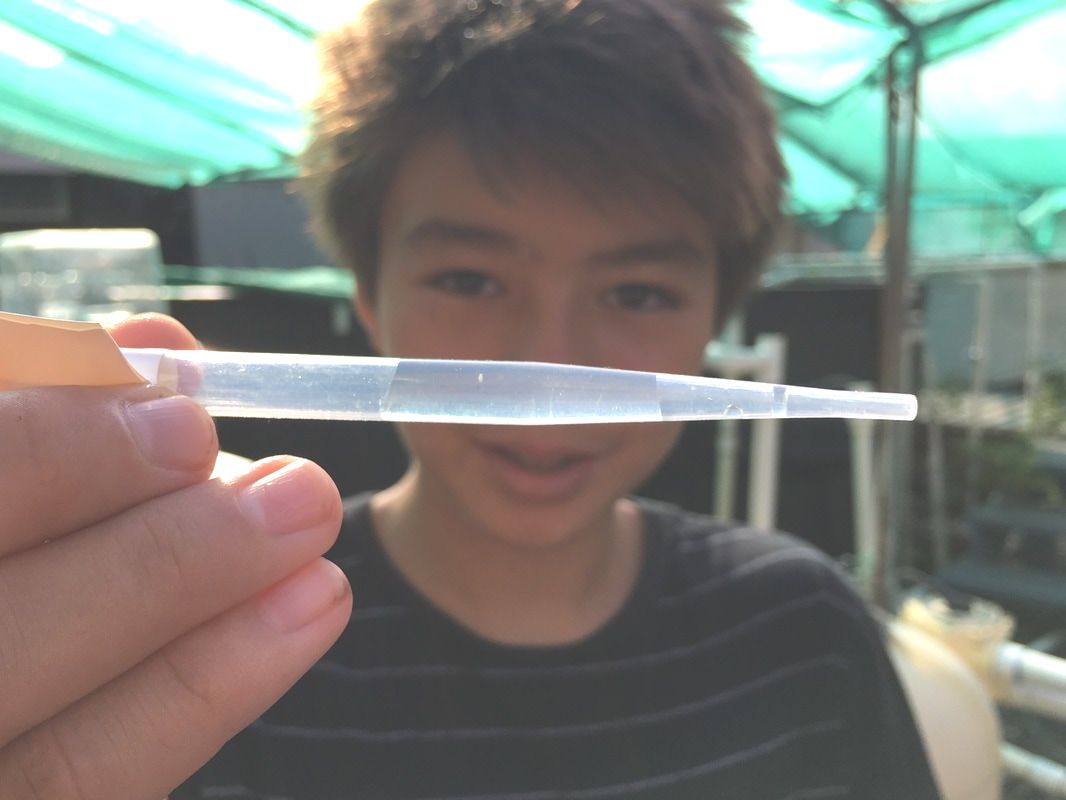

Rising and Shining The sun rose and so did our group this Sunday morning. We only had four hours left on the island and we wanted to make the most of it. After packing up camp and eating breakfast, we were ready for action. Counting Coral Larvae We have babies! I am happy to report that many of the corals in the experiment released larvae overnight. Students worked together to count hundreds of coral babies and then shared these data with Raphael. We all appreciated observing the tiny planktonic coral larvae, a life stage of the animal not usually seen.

Giving Thanks A big mahalo to the 15 7th graders on this marine science enrichment trip. I appreciated your enthusiasm and cooperation during our time together on Coconut Island. Your insightful questions, passion for field work, and clever humor made the trip a success! I hope this experience has inspired you to care for our ocean and possibly pursue a career in marine science. And a big mahalo to each of the following people:

|

AuthorThis blog contains occasional dispatches from my science classroom and professional learning experiences. Thank you for reading! Archives

December 2021

|

|

Cristina Veresan

Science Educator |

Proudly powered by Weebly

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed