|

The Bird Cliff at Kapp Fanshawe I hate to admit this, as curious as I am about the natural world, I have never really considered myself a bird person. I have a tough time using binoculars, and I feel like I can never see what birders get that excited about-- literally. Unless it's a big wading bird, I cannot even get a good look and certainly not a good picture. My Mentor Naturalist Karen talks about birds with such passion, though. When I see her on the bridge early this morning, she tells me, "We saw an ivory gull!" and I want to share her excitement as she relates how these birds often follow bears to scavenge their kills. When another naturalist explains how the little Arctic tern migrates from the high Arctic all the way down to Antarctica and back again in a year, I can appreciate this record-breaking accomplishment. And when I am hiking out on the tundra, I love straining to hear the snow bunting sing out its solo tune. But birds still leave me feeling kind of ambivalent. That all changed at the Kapp Fanshawe bird cliffs. I dare anyone to spend some time cruising right below these towering cliffs crammed with a quarter million nesting murres and not be in complete awe of bird life. That's how I spent this morning. Once we sailed out of Bear Sound and through the Hinlopen Strait, we had made our way to this amazing point of land in Eastern Spitsbergen. As we approached the cliffs, I was dwarfed by the sheer rock cliffs rising hundreds of feet from the sea lined with shoulder-to-shoulder murres. I was deafened by bird noise. Oh, and did I mention the acrid guano smell?

That is, until the chicks are ready to leave the nest. At this point, usually at night, the father will call the chick down from the ledge for what might be a free fall into the sea. Selection at work! Surviving chicks swim away with their father, and he continues to provide food for them as they develop. I took my attention away from the cliffs for a second and looked down at the sea. There were a few ice floes that shone white above the water but glowed with a blue hue below the surface. Suddenly, two of the ice floes began moving. Fast. I turned to naturalist Doug Gualtieri, pointed down, and (foolishly) asked "Doug, why is that ice moving?"

Plank-ton of fun! I participate in plankton outreach with a local non-profit back in Hawaii, Kahi Kai ('one ocean' in native Hawaiian). For my voyage, they have given me a unique tool we use in our outreach for mobile microscopy: the Cell Scope. The Cell Scope contains powerful optics but easily connects to an iPhone in order to observe and photograph plankton. I facilitate an annual plankton lab with my students at Star of the Sea, but I never imagined I would get the chance to do one in the high Arctic! As excited as I am to observe the macro life up here in the Arctic, I am also interested in the micro life drifting undetected in these frigid waters. The base of this Arctic food chain, tiny plankton, was on my mind, and today I finally got a chance to conduct a plankton tow. The first officer Piers took me out in a Zodiac after shuttling guests, including Ellen, to shore for a hike. With us were Aimee to observe and photographer Sisse Brimberg to capture the action. The plankton net is a funnel shaped, fine-meshed net connected to a plastic bottle. When the plankton net is towed through the water for awhile, you get a concentrated sample of plankton in the bottle. As we cruised by Idunbreen glacier and I gripped the tow line as the plankton net streamed behind us in the icy water. Enjoy this slideshow of plankton tow images taken by the amazing Sisse Brimberg, and graciously provided to me for use on my blog. When I got back aboard the Explorer, I could see lots of organic matter suspended in the sample and, thankfully, some swimming plankton! I took a cursory look at my sample in the Zodiac landing area but quickly realized I needed to find a more suitable spot. So I took my sample and the Cell Scope up to the Observation Deck where I could interact with guests and enjoy the majestic alpine scenery. Over and over, I used a plastic dropper to draw up a small amount of water to put on a slide, put the slide on the Cell Scope, and tried to find as much plankton as possible. I was happy to explain to guests what I was doing and share my passion for plankton. Some guests put their iPhones in the Cell Scope and attempted to find and photograph plankton themselves. I let them know that we all depend on plankton not only for supporting marine food chains but also for the oxygen they release during photosynthesis. Considering how much of the Earth is covered with seawater, does it surprise you that plant plankton provide us with about 60% of the oxygen we breathe?

While I was playing with Plankton... Ellen had a fantastic hike on the rocky coast adjacent to Idunbreen Glacier and shared these images with me. Lindblad Expeditions provides guests the opportunity to explore pristine and remote places, and the company is guided by a strict set of Governing Principles that really sets them apart in their field. The principles outline the commitment to guest safety and the high level of service. But one that really sticks out for me is "Positively impact the areas we explore and in which we work." One of the ways we do that is to leave only footprints and take only photographs. When we are ashore, we do not take anything with us: artifacts, fossils, rocks, specimens, bones etc...However, Ellen's hiking group made an exception to the no-take rule when they cleaned a small area of plastic trash. Now that's a positive impact! Another Bear!

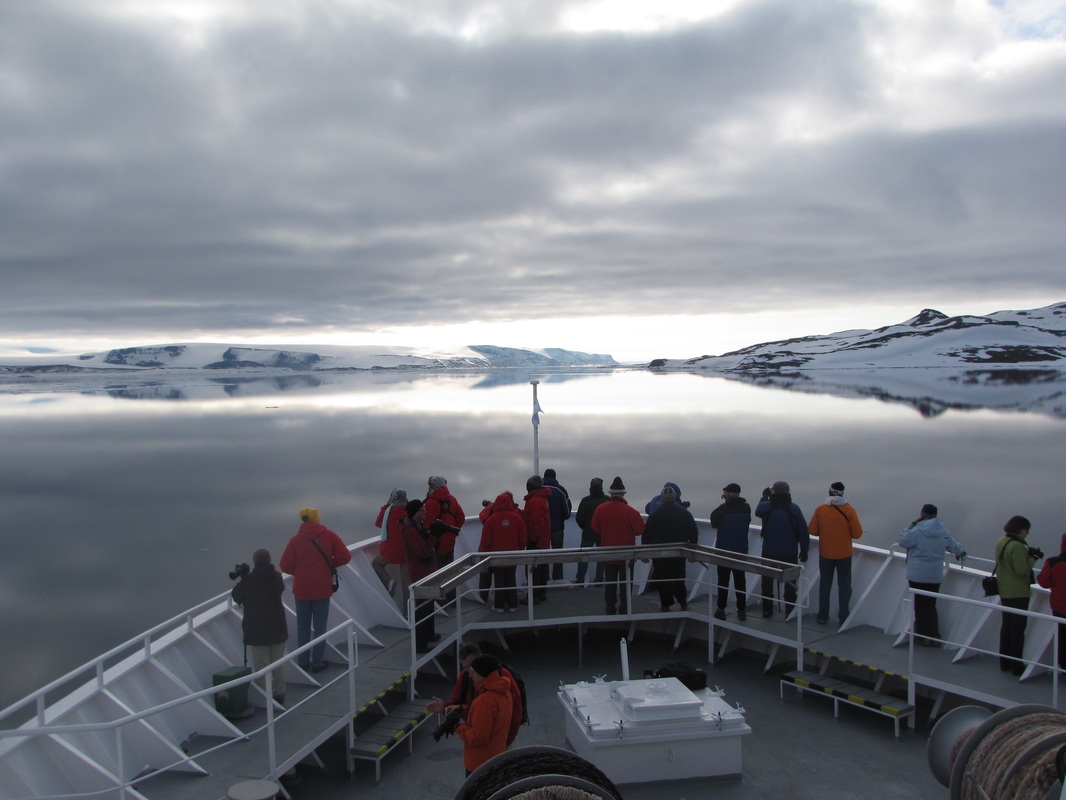

It was an awesome experience to once again observe a polar bear in its natural habitat. This large male bear appeared healthy and fat. We watched him walk across the ice with his huge paws, stopping every once and awhile to look up at our ship. Often, polar bears will roll on the ground after they swim to get the salt off them. But this bear in one amazing moment sprawled out on his belly! He came near the ship only once before lumbering away. I got thinking about a lecture that Magnus had given about polar bears. Polar bears diverged from brown bears in their evolution about 300,000-500,000 years ago and have adapted to their extreme conditions in both physical and metabolic characteristics. Because polar bears and brown bears can mate, there has been discussion in the scientific community about whether or not they are each different species, but recent genomic evidence confirms they are in fact unique species that have intermingled and interbred at various times. In fact, Magnus reported that due to climate change causing habitat to overlap, brown bears are again mating with polar bears in some parts of the world, and a few hybrid bears had been identified. The Day Winds Down... The silvery light in the high latitudes continues to amaze me. A group of us is gathered on the bow, taking in the scenery. When the water is this calm, the light so silvery, and the sky this full of wispy clouds, is it even possible to take a bad photograph? Gorgeous subject matter. I try not to think about the days of my voyage counting down, for I do not want this experience to end. Life aboard a ship has a sense of shared initiative and camaraderie like nothing else, and this ship is filled with such capable, fun, and interesting shipmates. Two of them are in my cabin right now. Aimee and Ellen are having another rich discussion tonight, dissecting our day and brainstorming all the ways we can incorporate our new learning into our curriculum. Oh, and there also might have also been some girl talk. All photographs by Cristina Veresan unless otherwise indicated.

Read the Lindblad Naturalist Daily Expedition Report (DER) here.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis blog contains occasional dispatches from my science classroom and professional learning experiences. Thank you for reading! Archives

December 2021

|

|

Cristina Veresan

Science Educator |

Proudly powered by Weebly

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed